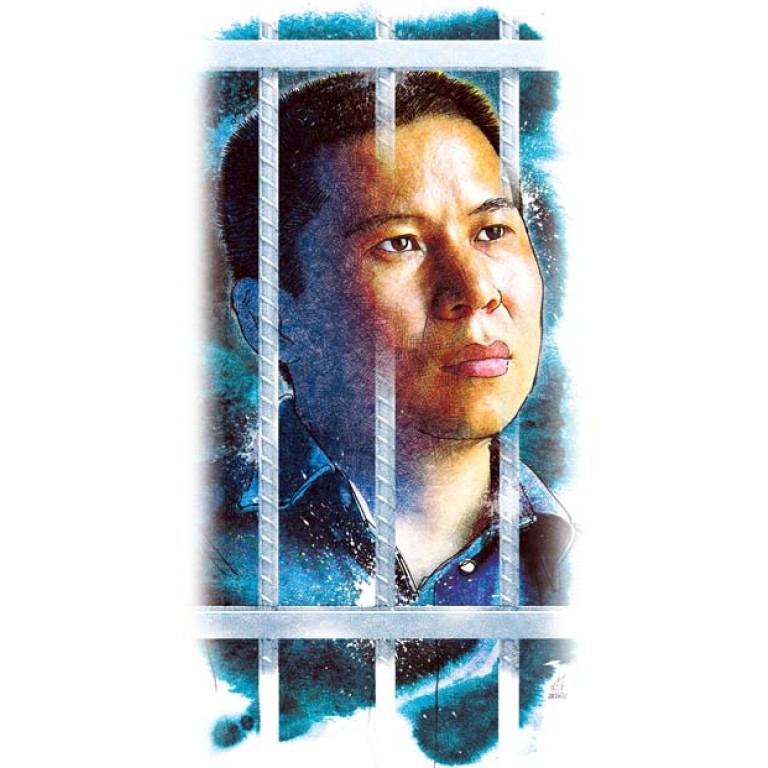

Xu Zhiyong's fight for a freer society

Xu Zhiyong's journey from lowly scholar to prominent pro-democracy activist has led him to prison, but his vision continues to gather force

Xu Zhiyong said that he wasn't afraid of jail.

"For the world to become a better place, someone has to pay a price," Xu said in a phone interview in late November 2012. "I think it's glorious to sacrifice for the sake of social progress and fighting injustice."

There was little public reaction. But nine days later, police detained him for nearly 40 hours.

Xu, 40, a law lecturer at Beijing University of Post and Telecommunications, founded the New Citizen movement in May 2012 to push for social equality and a fair legal system. In Beijing eight months later, fellow activists staged their first rally demanding state officials disclose their financial affairs.

Xu continued to protest with migrants who were asking that their children be schooled in Beijing. But the authorities saw these activities as a threat and within months Xu's words about freedom would prove prophetic.

He was detained under house arrest in April last year and formally arrested in August. Police accused him of "organising, masterminding and implementing" at least seven protests last year.

Last Wednesday he was tried in Beijing on a charge of "assembling a crowd to disrupt order in a public place". He was convicted four days later and sentenced to four years in prison.

At least 18 people associated with Xu's movement have been detained. Three participants in Jiangxi province were tried late last year and await a verdict.

Six other activists were tried on the same charge over the past week.

Today, as the authorities try to crush his New Citizen movement, Xu is one of the most prominent rights advocates on the mainland.

The movement's goals appear to echo Xi's stated desires to end corruption and unchecked power, but the activists' force may appear to officials to be a potential fledgling political party that could challenge party rule.

A low-profile scholar - an activist who knows him well - says Xu is pensive and lacks humour. Xu has said in his movement's manifesto and in court that his vision is that China will become "a country with freedom, justice and love". But he wasn't always seen as a radical troublemaker.

During the past decade, he has emerged from a life as a low-profile scholar and NGO founder to become a thorn in the side of the authorities. He once harboured hopes of working "within the system". In 2003 and 2006, Xu won seats as an independent member from the Haidian district to the People's Congress in Beijing - a body typically filled with party-appointed personnel.

Xu came to prominence a decade ago, as he and friends asked officials to end a form of arbitrary detention.

In mid-2003, a young migrant named Sun Zhigang was beaten to death in a police detention centre in Guangzhou.

Shocked, Xu and two fellow PhD graduates, Teng Biao and Yu Jiang from Peking University, wrote to the National People's Congress Standing Committee, asking that it review procedures on detaining and repatriating non-city residents.

The next month, then-premier Wen Jiabao announced that the state would abolish the directive affecting vagrants and beggars. State broadcaster CCTV named the three law graduates as top legal figures of the year.

Many people with grievances started contacting the young scholars. They started a small NGO, Sunlight Constitution, in October 2003, which later became Gongmeng, or Open Constitution Institute, a non-profit legal aid centre that provided free legal advice.

Gongmeng sent clothes and food to petitioners and challenged so-called "black jails", extralegal detention centres. The nonprofit campaigned for migrants' children, homeowners forced from their residences, and death-row inmates, and sought legal redress for parents whose babies had been poisoned by melamine-tainted milk. The nonprofit also produced an independent assessment of the cause of mass riots in Tibet in 2008.

In 2009 the authorities closed Gongmeng, accusing it of taxevasion. Xu was taken into custody for nearly a month. Once he was released, he was barred from resuming his teaching post at Beijing University of Post and Telecommunications.

Xu promised to compromise more, but he still insisted that China's myriad social problems stemmed from its problematic political system.

"[Officials] are accountable to people above, but not below," he said at the time. "So we need to push for political reform."

Xu and his lawyer friends continued their rights work under the new name Gongmin, or The Citizens' Pledge. It asked participants to fight corruption and injustice in their lives and pledge to live in honesty and integrity. That became the basis of the New Citizen movement.

By November 2012, Xu estimated that the New Citizen drive had drawn 5,000 supporters from across the country.

Its participants communicate through social media, but also meet once a month over dinner to discuss social issues. They dubbed the affairs with the ironic name , or "same-city dinner gatherings", which sounded in Mandarin like the phrase, "committing crimes in the same city".

Around then, Xu said the police stepped up their surveillance of him. When he tried to meet associates and supporters, or during politically sensitive times such as a party congress, he was often barred from leaving home.

In December 2012, emboldened by Xi's vow to end corruption, the New Citizen members decided to ask the country's top 205 officials to detail their families' wealth. By early March, they had submitted 7,000 signatures to the National People's Congress asking the newly chosen central committee members to disclose their assets. Several activists staged a noisy protest in Xidan Culture Square in Beijing on 31 March. Within weeks, eight activists were detained. In mid-April, Xu was placed under house arrest. In July, police detained him on charges that led to his trial.

Rights groups and legal experts say the punishment of Xu and his fellow activists shows the government's determination to crush public displays of protest.

"By making him the poster boy for punishment, Xi is trying to show zero tolerance for any activity, however intrinsically desirable, that is not monopolised by the party," said China law expert Professor Jerome Cohen at New York University in New York.

Legal experts said the seven New Citizen trials were studded with procedural flaws. Witnesses and co-defendants could not testify. Academics also said the vagueness of the charge meant it could be used as a catch-all to prosecute any protestor.

"The rule of law demands certainty and one should not be punished by a criminal law that is still fuzzy," said Fu Hualing, law professor at the University of Hong Kong.

Eva Pils, a Chinese law expert at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said the authorities were trying to quash the New Citizens movement because they saw a worrying trend: connections being built among citizens from a broad strata of Chinese society, including lawyers, scholars, rights activists and petitioners.

"The crackdown is very intense now … because the government has not been able to control such actions as well as it used to," she said.

Observers and rights activists say the prosecution of New Citizen activists, and the wider efforts to crackdown on government critics, won't prevent more people from demanding broader rights.

"These sentences certainly do nothing to stop the sense of grievance that motivates people to come out in the streets," Pils said.

Xu is said to have remained calm during the trial. His lawyer, Zhang Qingfang , said that days before the proceedings, he showed his client a picture of his newborn daughter. Xu cried.

In a note to her husband posted by friends online, Xu's wife said that her husband's ideals had driven him to prison, but that she respected his choice.

"I don't blame you at all for today's outcome," his wife, Cui Zheng, wrote. "It's because fate has really pushed you to the point where you must make a choice to persist and give up everything else."

During his trial, Xu, his lawyer said, told the court that the government harboured "fear of the free society nearly upon us.

"By trying to suppress the New Citizen movement," he said, "you are obstructing China on its path to becoming a constitutional democracy through peaceful change." Officials stopped him speaking after 10 minutes.