Twenty-five years after his death, Hu Yaobang still remembered as pragmatic reformist

Twenty-five years after his death, Hu Yaobang is still remembered by many, even including some of his former foes, as one of the most popular Communist Party leaders for his pragmatic reform policies and humanistic, liberal-leaning approach.

Twenty-five years after his death, Hu Yaobang is still remembered by many, even including some of his former foes, as one of the most popular Communist Party leaders for his pragmatic reform policies and humanistic, liberal-leaning approach.

The low-key visit to Hu Yaobang’s old residence last week by former president Hu Jintao is perhaps most telling about the Communist Party’s attitude towards its former leader. Even after an official taboo over commemorating Hu was lifted in 2005, Party officials still remain cautious about the reformist whose death in 1989 sparked a democracy movement that changed China forever.

He was a staunch proponent of opening the economy as rapidly as possible and scrapping Stalin-Maoist dogma in favour of pragmatic steps to develop the economy

Xigen Li, a professor with City University of Hong Kong’s department of media and communication, said that Hu Jintao only visited his former mentor’s residence in Hunan province after his retirement as he was careful in avoiding controversy.

“His visit to Hu Yaobang’s residence can be seen as just being personal and thus avoid any political controversy,” Li said.

Handpicked and groomed by Hu Yaobang, the younger Hu gradually climbed up the ladder of the Youth League and the Communist Party. The two Hus are not related.

Tuesday marks the 25th anniversary of the death of the former party chief.

“He was the most reform-minded and liberal leader within the Chinese Communist Party,” said Xiaoyu Pu, professor of Political Science with the University of Nevada, Reno.

“Hu was probably the most genuinely open-minded to ideas outside of China and [outside] the Communist Party tradition,” said Steve Tsang, professor of Contemporary Chinese Studies and director of China Policy Institute with University of Nottingham.

Among other things, Hu was credited with spurring economic reforms after the Cultural Revolution, clearing the names of thousands of people persecuted during the tumultuous decade and a drive towards further political reforms. “He was a staunch proponent of opening the economy as rapidly as possible and scrapping Stalin-Maoist dogma in favour of pragmatic steps to develop the economy,” said Zhang Lifan, a party historian.

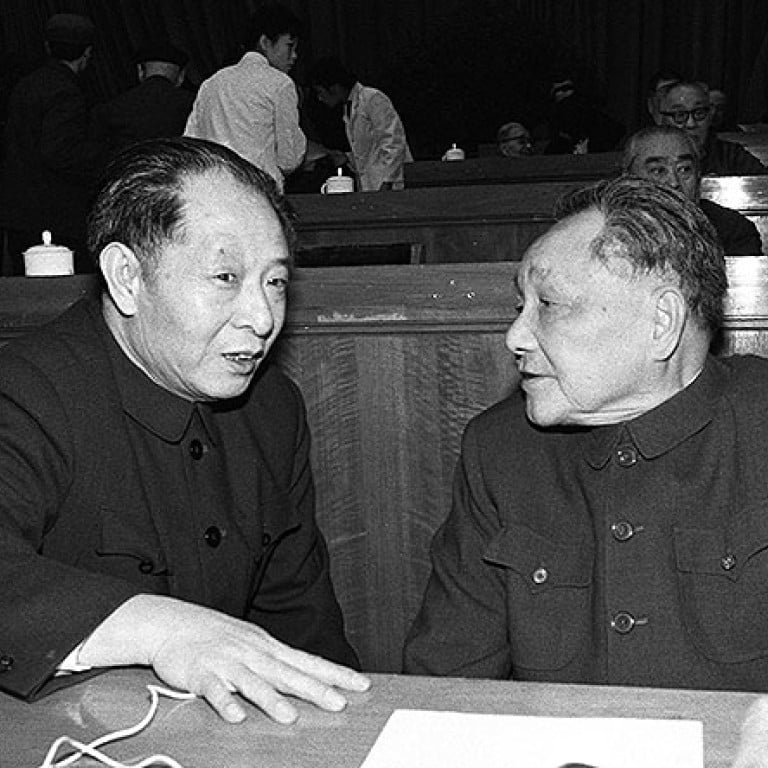

Hu had also played a critical role in helping his long-time mentor, Deng Xiaoping, gain and consolidate power in the late 1970’s. In the early- and mid-1980’s, he was in charge of day-to-day matters during China’s liberalisation and economic reform.

Some analysts have described the relations between him and Deng as similar to those between a chairman and the CEO in a modern corporation.

“If Deng Xiaoping was the chief architect for China’s reform and opening, then Hu Yaobang deserves to be called its chief engineer,” said Zhou Ruijin, a reformist party propagandist who was best known for co-authoring a series of influential commentaries supporting Deng’s reform.

But Zhang said that Hu had done more than just assisting Deng.

“He was also a creator and a pioneer as he initiated a series of thought liberalisation movements in late 1970s which were only supported by Deng later,” said Zhang, formerly with Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

In a nation where caution is the safest tactic in politics, Hu was the exception. He was one of the first Chinese leaders to abandon the Mao suit in favour of western-style jacket and tie.

Some analysts described him as a voracious reader and tireless investigator of the real situation in many areas in China, who often expressed opinions that stray from rigid communist orthodoxy.

He once surprised many by suggesting that the Chinese start using Western utensils. “We should prepare knives, forks, and plates to eat Chinese food each from one’s own plate,” he urged. “By doing so, we can avoid contagious diseases.”

When Hu was General Secretary of the Communist Party, he tried to experiment with ideas that would later prove unacceptable to Party elders including Deng, but he did succeed in giving Western and liberal ideas more room to contend with the prevailing Dengist-Leninist model that replaced Maoist totalitarianism after the Cultural Revolution.