Back to the future: Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Middle East visit ... and his Middle Kingdom dream

Beijing wants to boost its political, diplomatic and military ties and help promote nation’s international influence the way Middle Kingdom was regarded 2,000 years ago

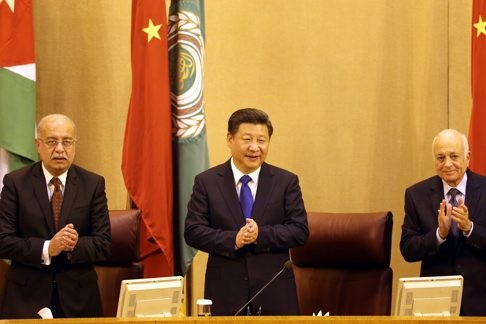

It is often said that history has a habit of repeating itself. If that holds true for global affairs, then President Xi Jinping’s (習近平) whirlwind trip this week to Iran, Saudi Arabia and Egypt should be seen as a modern-day equivalent of China’s exploration of Central and West Asia 2,000 years ago.

Xi’s visit to the Middle East, his first since he came to office three years ago, is aimed at boosting his programme to rebuild the Silk Road network of trade routes, formally established during the Han dynasty (206BC-AD220), that linked the regions of the ancient world in commerce.

China has good reasons to attach such importance to the Middle East because the world’s second-largest economy and leading manufacturer relies on oil from the Gulf – where more than half its imports originate – to fuel its growth.

Moreover, Beijing worries about extremists in the region providing training and inspiration to Muslim separatists in western China, which has a Muslim population of about 40 million.

Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia are important potential staging grounds for projects that will provide income streams for Chinese corporations and relieve China’s domestic economic overcapacity

Xi has chosen the Middle East as his first foreign destination in 2016, which suggests he sees it as a priority.

By comparison, Xi’s first trips abroad in 2013 and 2014 were to Russia, and in 2015 to Pakistan, China’s all-weather friend in Asia. Xi’s two predecessors Jiang Zemin (江澤民) and Hu Jintao (胡錦濤) both visited Egypt– Jiang in 2000 and Hu in 2004.

Zhiqun Zhu, a professor at Bucknell University in the United States, said Iran, Saudi Arabia and Egypt were China’s most important partners economically and diplomatically in the region. He noted that Egypt was the first Middle Eastern country to recognise communist China in 1956.

China and Egypt are key members of the non-aligned movement, while Saudi Arabia and Iran have been the top oil providers to China in the past two decades.

“The visits are meant to consolidate China’s long-standing relations with these countries,” Zhu said.

As part of Xi’s stated aim for the “revitalisation of the Chinese nation”, Beijing is emphasising its relationship with the region.

Xi has advocated the new Silk Road programme, also called “One Belt, One Road”, under which China wants to create an economic land corridor along the original Silk Road through Central Asia, West Asia, the Middle East and Europe. The plan includes a maritime route that links China’s coast with port facilities in Africa, pushing up through the Suez Canal into the Mediterranean.

It enabled Chinese envoys to explore the Central and West Asian markets and promote exchanges among different people, cultures and religions.

The ancient Silk Road also played a significant role in the flourishing of some of China’s most magnificent cities.

READ MORE: Key facts behind China’s warming ties with Saudi Arabia, Iran and Egypt as Xi Jinping signs mega oil deals during his Middle East tour

The terrain along the route is home to many of the world’s largest rivers, which nurtured some of the world’s greatest civilisations. These cities helped to knit together various cultures from before the time of Alexander the Great (356-322BC) up to the advent of the Industrial Age in the late 18th century.

At its height, in the mid-8th century, the Tang dynasty (618-907) ruled most of the regions of the Silk Road as the influence of the Chinese emperor grew from an increase in population, which in turn produced a much larger market for trading.

On Wednesday, China issued its “Arab Policy Paper” which, given the history of Sino-Arab relations, from the ancient Silk Road to the founding of the Sino-Arab State Cooperation Forum in 2004 – suggests such past successes can be repeated.

READ MORE: China agrees to fund infrastructure projects in Egypt and help develop nation’s economy

Historians often say the most valuable legacy of the ancient Silk Road was the exchange of cultures, ideologies and religions between different nations.

However, Benjamin Herscovitch, a research manager at China Policy, in Beijing, said that culturally and ideologically, China and Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia were at best estranged and at worst in opposing camps.

Herscovitch said China’s Communist Party was not only atheist, but positively anti-religion. Beijing’s repressive policies in Xinjiang (新疆), its suppression of Christian groups, and its aggressive campaigns against quasi-religious groups such as Falun Gong were testament to its hostility.

In contrast, religion in Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia was integral not only to culture and everyday life, but also politics and the institutions of state.

But Herscovitch said China was able to bridge the divide because of shared strategic and economic interests.

The three Middle Eastern countries are active supporters of Xi’s Silk Road initiative and his trip will highlight a new incentive for bilateral transport and communications interconnectivity and indicate a new direction for bilateral cooperation.

READ MORE: Chinese President Xi Jinping pushes trade over politics in Middle East

Xi hopes the initiative can create the potential for a new and even larger market boosted by modern technology.

Zhu said China’s primary interests in the Middle East were economic and strategic and therefore Xi’s visits would focus on energy and economic ties.

Herscovitch said Cairo, Tehran and Riyadh were all valuable partners for Beijing in its efforts to extend and consolidate its web of One Belt, One Road investments across Eurasia and Africa.

“Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia are, therefore, important potential staging grounds for projects that will provide income streams for Chinese corporations and relieve China’s domestic economic overcapacity,” Herscovitch said.

For oil exporting countries such as Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia, deeper economic ties with China were crucial, not only because of the voracious Chinese hunger for hydrocarbons, he said. In the context of plummeting oil prices, Chinese investments were a welcome boost at a time of general economic woe.

Laurence Brahm, an international lawyer and human rights observer, who has participated in Palestinian peace talks, said China’s Middle East policy was driven by multiple factors.

Under Xi there was an effort to reconstruct the non-aligned movement in the context of a new financial architecture emerging around the globalisation of China’s currency, the yuan, he said.

The Middle East was a key player in this, especially the pricing of key commodities in yuan. The Gulf states also serve as a de facto financial centre for the African continent, where China has enormous and complex interests.

Another aspect of this financial architecture was an effort to push for a Silk Road consensus involving all of the Central Asian states. Of course, Iran played a key role in the consensus, Brahm said.

Analysts said that for years China focused its attention primarily on its periphery, but as its economy grew Beijing needed to come up with a strategy to deal with the rest of the world. They said Xi was actively boosting China’s international footprint and sphere of influence to a level commensurate with its fast-growing economic and military power.

His assertive diplomacy in the Middle East is also a response to the US military presence in China’s neighbourhood, and Washington’s domination of Middle Eastern affairs.

The US’ traditional posture in the Middle East and the strategic relations it has with virtually all regional governments makes China feel vulnerable.

Chinese diplomats believe that Washington’s ability to affect China’s maritime ties with the Middle East has increased after two US-led wars in Iraq and the so-called ‘War on Terror’.

In recent years, China has spared no effort – from pursuing pipelines across the Central Asian steppes to developing port facilities in Burma – to ensure that its energy supplies such as oil shipments can bypass the Straits of Malacca, the main shipping channel linking the Pacific Ocean to the Indian Ocean, which the US Navy could conceivably control.

However, until recently, China’s interactions with Middle Eastern nations in general were largely limited to economic exchanges. China maintained a low-key stance when it came to the most critically important arena in Middle East diplomacy – the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – preferring to leave things to other global powers.

Zhu said China was the only global power that maintained strong relations with all Middle Eastern countries, and that Beijing was now keen to project itself as a major global power.

“However, China is not likely to serve as an honest broker to resolve regional disputes, such as the feud between Saudi Arabia and Iran,” Zhu said.

China’s main foreign policy objective had been to seek economic cooperation to buttress domestic growth since Deng Xiaoping’s (鄧小平) reforms began in the late 1970s, he said.

Herscovitch said that Beijing would be at pains to avoid tangling itself too closely in the region’s sectarian conflicts.

“We should not expect China to take on the kind of North African and Middle Eastern security responsibilities presently assumed by the US, Russia, Great Britain and France,” Herscovitch said.

Kerry Brown, a professor of Chinese studies and director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London, said that so far Beijing had managed to keep a distance from the endless political problems in Middle East.

“But those days might be coming to an end,” Brown said, citing the stand-off between Iran and Saudi Arabia over Riyadh’s execution of a prominent Shiite cleric.

Chinese had been taken hostage and executed by Islamic State militants, and the civil war in Syria had caused China to hint at getting more involved, Brown said. “So it will try to balance things between not getting embroiled, but looking after its interests, which are increasing there,” Brown said. “As each day passes, though, that grows more difficult.”

However, Xi, as the leader of the world’s second-largest economy, apparently wants a US-style global leadership role.

Under his presidency, China has embarked on a noticeably more proactive diplomacy in the region. Diplomats note that China has never before issued a government paper outlining its policy on the Arab nations. The issuing of such a policy paper is a major step showing Beijing’s growing strategic interest in the region.

Xi’s high-profile diplomacy has only added to the belief that in Middle East affairs, Beijing wants to be taken seriously as a major player, just as the Middle Kingdom was all those years ago.