Anti-Soviet genesis of Cultural Revolution set stage for Chinese diplomatic revival

Mao regarded Soviet Union as bigger threat than United States

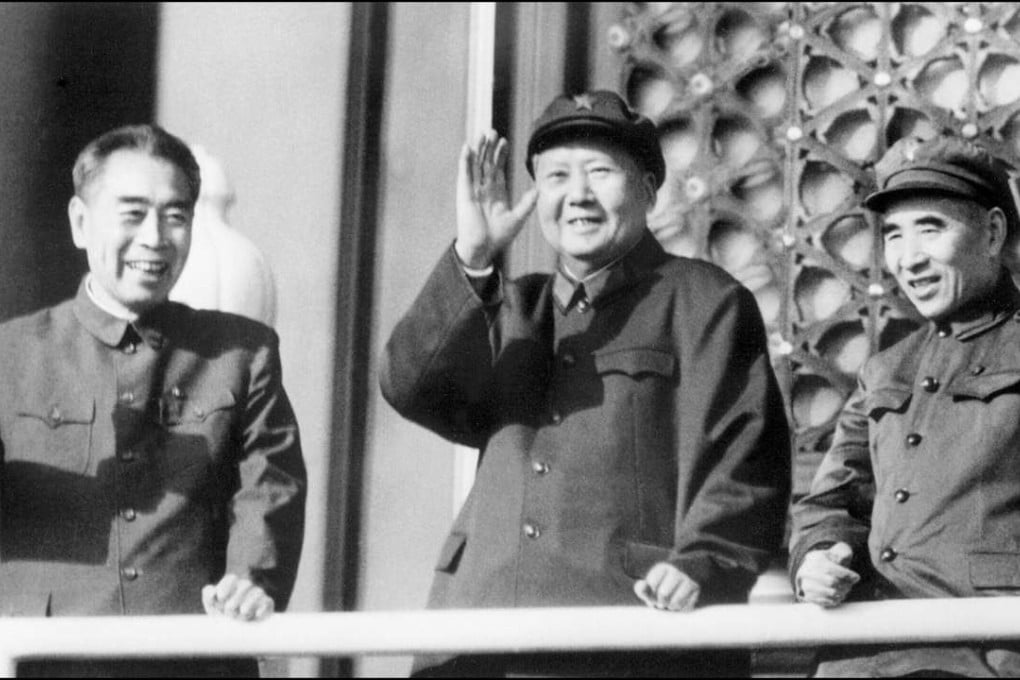

For most historians the key date is May 16, 1966, the day Mao Zedong set in motion the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution to purge the country of revisionist elements.

In the five decades since, much of the discussion has focused on the way the turmoil reshaped and traumatised China, beginning as a power struggle between Mao and his politically moderate colleagues led by president Liu Shaoqi.

Mao wishes to lead the world anti-imperialist movement, and so he has to discredit Khrushchev

It is characterised as a largely domestic political campaign that marked a return to leftist political orthodoxy and Mao’s re-emergence on the national stage.

But the roots of the Cultural Revolution go back much further and stretch beyond China’s borders.

The movement also resulted in a dramatic and yet unexpected shift in foreign policy towards pragmatism, a change that shaped global geopolitics for years to come and ran counter to the direction at home.

The origins of the Cultural Revolution go back to the death of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and his subsequent denunciation by successor Nikita Khrushchev in the mid 1950s. At the 20th congress of the Soviet Union’s Communist Party, Khrushchev denounced the personality cult around the dead leader. Khrushchev also ushered in a degree of relaxation of the media and introduced a series of economic reforms.