Chain reaction: will nuclear plant decision herald tougher times for Sino-British ties?

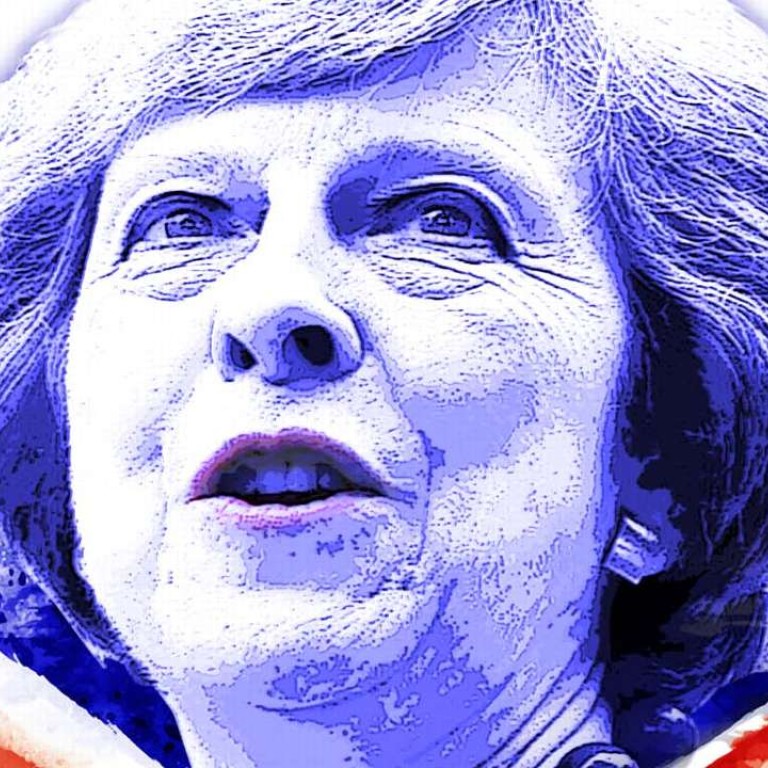

In the first of a series of stories on China’s relations with other G20 members ahead of the G20 summit in Hangzhou, the South China Morning Post looks at the roller-coaster ride Sino-British relations went through in six years under former British prime minister David Cameron and the fate of a much vaunted ‘golden era’ in bilateral ties under his successor, Theresa May

Deal or no deal? The new British government’s 11th-hour decision to reconsider a proposed nuclear joint venture with China is not just about business, but also about the future of diplomatic relations between two influential nations.

It is no longer ‘investment at any cost’ which seemed to be the approach under Cameron and Osborne

It not only casts a shadow on recent, dynamic Sino-British economic cooperation, but also risks taking the sheen off a hard-won “golden era” of “special relations” between the world’s second- and fifth-largest economies. That China is the world’s last major communist-ruled nation and Britain a major Western democracy only adds to the stakes, along with the fact that they are both permanent members of the UN Security Council.

Just hours before a scheduled signing ceremony on July 30, Theresa May, the new British prime minister, announced Britain was postponing approval of the £18 billion (HK$183.2 billion) Hinkley Point nuclear power station, apparently because of security concerns about Chinese investors involved in the project.

Multimedia: G20 in Hangzhou – the face of China’s heritage, achievements and aspirations

The reaction of China’s state-run media went as far as warning that the decision could spell the end of the “golden era” in bilateral relations proclaimed by President Xi Jinping and May’s predecessor, David Cameron in October last year during Xi’s high-profile state visit to London, when he was met with the “reddest red carpet”. Commentaries in state media were overwhelmingly sceptical about the new British leader’s China policy, describing May as a conservative politician who was as tough as her female predecessor Margaret Thatcher, dubbing her Britain’s second “iron lady”.

Analysts said the decision had clouded the future of Sino-British relations in the post-Brexit era following Britain’s June vote to leave the European Union. They said the strength of the bilateral relationship would be tested when Xi and May meet next month on the sidelines of the G20 summit in the eastern Chinese city of Hangzhou.

Feng Zhongping, an expert on Sino-British relations and director of European studies at the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations in Beijing, said the meeting, May’s first with Xi as British prime minister, would “set the tone of post-Brexit relations”.

Most analysts agreed that any decision to stop the project would have a serious impact on overall relations.

Seen as a flagship project of bilateral cooperation and the highlight of Xi’s trip to Britain last year, the Hinkley Point joint venture, also involving France, served as a symbol of the friendship and cooperation between China and two major European powers against the backdrop of increasing rivalry between China and the United States for global supremacy.

Xi said the project had elevated Sino-British ties to an unprecedented level of warmth and cooperation. Analysts said failure of the deal would damage Chinese ambitions reaching far beyond the project itself.

Beijing saw it as a prestige project to showcase China’s technological prowess after Chinese nuclear firms were promised they could develop a future reactor, most likely of their own design, for another British plant.

Xi was hailed domestically for bringing home such a major infrastructure agreement. Beyond the financial boost, Chinese commentators saw the joint venture as a demonstration of renewed faith in the communist leadership’s economic management.

The venture also fit neatly into Xi’s cherished “One Belt, One Road” strategy to export China’s industrial overcapacity and was portrayed as a huge diplomatic success, showing that Britain was buying into Xi’s “new diplomacy” narrative.

If the deal is shelved, it may be seen as a blow to Xi due to his personal involvement in the project, given that he witnessed the signing of the deal with Cameron.

It would be a blow to the Chinese joint-venture partner, China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC), a military-industrial concern. The company sees the British project as a springboard to the international market.

Analysts said the announcement that approval for the project had been postponed had raised the level of uncertainty in the “special” relationship.

“The exceptional relationship is under severe strain,” Kamel Mellahi, a professor of strategic management at the University of Warwick’s business school, said.

He said the reasons given for the postponement, real or otherwise, were certainly not aligned with the spirit of the “win-win, reciprocal, long-term, trust-based relationship” the two countries had been trying to develop and were likely to have an adverse impact in the short and medium term.

Some diplomatic observers see the May government’s possible withdrawal from the project as marking a dramatic shift in tone for the British government after Cameron and his finance minister, George Osborne, spent years fostering closer relations with Beijing.

For most of the past century, British foreign policy was built on its “special relationship” with the US, which replaced Britain as the world’s most powerful nation following the second world war.

The Sino-British relationship under Cameron’s Conservative-led government, which took office in May 2010, was something of a roller-coaster ride. However, by last year it had gone a long way to forging another “special relationship” – with China.

Cameron’s first visit to China as British prime minister, in 2010, was close to a disaster as he flew home almost empty-handed despite having arrived at the head of the largest British trade delegation to Beijing in more than 200 years and with high hopes of returning with a suitcase full of deals. Eighteen months later, in May 2012, his high-profile meeting with the Dalai Lama plunged bilateral relations into the deep freeze. They only recovered during another visit to China in December 2013, after Downing Street ruled out any further meetings with the Tibetan spiritual leader. On that visit, which secured £6 billion in trade deals, Cameron promised Chinese investors a “warm welcome” in Britain. Premier Li Keqiang reciprocated in a visit to London in June 2014, arriving with another batch of trade deals that paved the way for Xi’s 2015 visit.

The Sino-British “special relationship” has been criticised by Washington amid escalating tension between the US and China as the world’s most powerful nation and its fastest rising one compete in fields ranging from the setting of rules for trade and investment, perceptions of human rights and regional and global security.

Beijing viewed Britain’s decision to become the first of the US’s Western allies to apply to join the US$50 billion, China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in March last year, despite strong opposition from Washington, as a defining moment in Sino-British relations. While Osborne described bank membership as the driving force behind developing closer economic ties, in a rare public breach of the transatlantic “special relationship” a senior US official slammed it as part of a trend of “constant accommodation” of the Chinese government.

Washington sees the AIIB as a Chinese effort to challenge US-dominated Bretton Woods institutions, such as the World Bank, formed in 1944 to help steer the international financial system.

Britain’s high-profile and lavish treatment of Xi during his visit last year triggered widespread criticism in the West, particular among American commentators.

Feng said Beijing had attached a great deal of strategic significance to its ties and cooperation with London, seeing them as useful bargaining chips in its competition with the US.

“China sees Great Britain as one of the most influential nations in the world,” Feng said.

But Kerry Brown, professor of Chinese studies and director of the Lau China Institute at King’s College, London, said that “clearly, under May, there is a cooler attitude towards China”.

“It is no longer ‘investment at any cost’ which seemed to be the approach under Cameron and Osborne in their final two years in power,” said Brown, a former British diplomat who once served as first secretary at the British embassy in Beijing.

On a visit to China in September last year, Osborne promised the start of a “golden era” and announced the British government was committed to allowing Chinese involvement in the Hinkley Point project.

In a speech at the Shanghai Stock Exchange he outlined what became known as the “Osborne Doctrine”, vowing to “make Britain China’s best partner in the West” and “create a golden decade for both countries”.

But diplomatic observers said May never supported Osborne’s “gung ho” approach to Chinese investment, fearing it could compromise Britain’s national security. However, May gave her finance minister, Philip Hammond, the task of reassuring Beijing that post-Brexit Britain would still be “open for business”. On the sidelines of a meeting of G20 finance ministers in Chengdu in late July, Hammond also raised the possibility of negotiating a free-trade agreement with China once Britain left the EU.

Beijing, however, is suspicious that May might be reversing Cameron’s China policy, even though some have argued that the Brexit vote has increased the political urgency for London to adopt a China-friendly policy because it now needs more Chinese investment than ever before to offset the negative impact of its exit from the EU. They have also warned that expectations of a surge in Chinese investment will not be realised if the “special relationship” is not maintained. Beijing had said it expected to see as much as £100 billion invested in Britain over the next decade.

Hongyi Lai, a professor of contemporary Chinese studies and politics at Nottingham University, said it was possible that May would adopt “a slightly different approach to China compared to Cameron and Osborne”.

“However, from the economic point of view, discouraging China’s investment will not bode well for the UK economy given the uncertainty from Brexit,” Lai said.

Mellahi said a post-Brexit Britain was going to need such a “special relationship” more than ever before.

“Brexit may free Britain from the EU’s shackles and enable it to strike some special deals with China, but the downsides far outweigh any supposed upsides,” Mellahi said. “For sure, the relationship is going to look substantially different from the one envisaged.”

Brown said there would be a much more cautious and careful approach under May’s cabinet. But as Britain prepared for Brexit, London needed to seek good-quality trade and investment partners outside the EU, with China being an obvious candidate.

“It is therefore a complex message to send to China that on the one hand, the UK wants an upgraded and new relationship in terms of investment and trade with them, but on the other hand it also wants to be very strict on the kinds of sectors and the terms it takes this collaboration,” Brown said.

Recent developments, he added, suggested that “the ‘golden era’ was too short to really show if it was ever likely to work”.

Timeline of modern Sino-British relations

1950 – Britain recognises the People’s Republic of China as the legal government of China

1954 – The two countries establish diplomatic relations

1972 – The two countries sign an agreement on the exchange of ambassadors

1979 – Premier Hua Guofeng becomes the first Chinese leader to visit Britain

1982 – Margaret Thatcher becomes the first British prime minister to make an official visit to China

1984 – Thatcher visits China for a second time and the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong is signed

1986 – Queen Elizabeth visits China and meets leader Deng Xiaoping

1991 – John Major becomes the first Western leader to visit China after the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown

1997 – Handover ceremony on June 30 marks the transfer of sovereignty over Hong Kong from Britain to China

1998 – British and Chinese premiers exchange visits, establishing the Sino-British comprehensive partnership

1999 – President Jiang Zemin makes first state visit to Britain by a Chinese president and meets the queen

2004 – Premier Wen Jiabao pays an official visit to Britain and the two countries establish a comprehensive strategic partnership

2005 – President Hu Jintao pays a state visit to Britain

2008 – British Prime Minister Gordon Brown attends the closing ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games

2010 – British Prime Minister David Cameron leads largest trade delegation to China in 200 years

2012 – Cameron meets the Dalai Lama, angering the Chinese government

2013 – Cameron leads another trade mission to China

2014 – Premier Li Keqiang visits Britain and meets the queen

2015 – President Xi Jinping signs more than £30 billion of trade deals on state visit to Britain