Is Beijing’s hardline stance on border rows blowing its defence diplomacy?

Chinese army’s increased transparency offset by aggressive stance in territorial disputes

China’s military has increased its global visibility and transparency in the past four years under President Xi Jinping, showcasing its military prowess with newfound confidence, but Beijing’s aggressive postures in territorial disputes with neighbours have offset some of the trust gained by such defence diplomacy.

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has established a global footprint in recent years, with its navy crossing every ocean and peacekeepers deployed to faraway continents.

Three PLA Navy vessels – the guided-missile destroyer Changchun, guided-missile frigate Jingzhou and supply ship Chaohu – are currently engaged in the longest voyage in Chinese naval history since Zheng He’s 15th century expedition.

The flotilla, led by Rear Admiral Shen Hao, deputy commander of the East Sea Fleet, is visiting around 20 countries in Asia, Europe, Africa and Oceania on its six-month mission, making port calls to its potential partners in Beijing’s “Belt and Road” trade-development initiative.

Observers said projecting China’s influence and protecting its interests overseas were key purposes of such moves, or as Shanghai-based military commentator Ni Lexiong put it: “military diplomacy serves political purposes.”

Zhou Chenming, a Beijing-based military commentator, likened it to a celebrity’s need for a bodyguard.

“Since Chinese business is going global, the PLA will have to follow in its steps to protect Chinese citizens and companies and China’s economic interests,” he said.

The story began in 2008, when the first batch of PLA warships sailed to the Gulf of Aden to take part in anti-piracy patrols. That was followed by a series of rescue and evacuation missions in waters near the Horn of Africa.

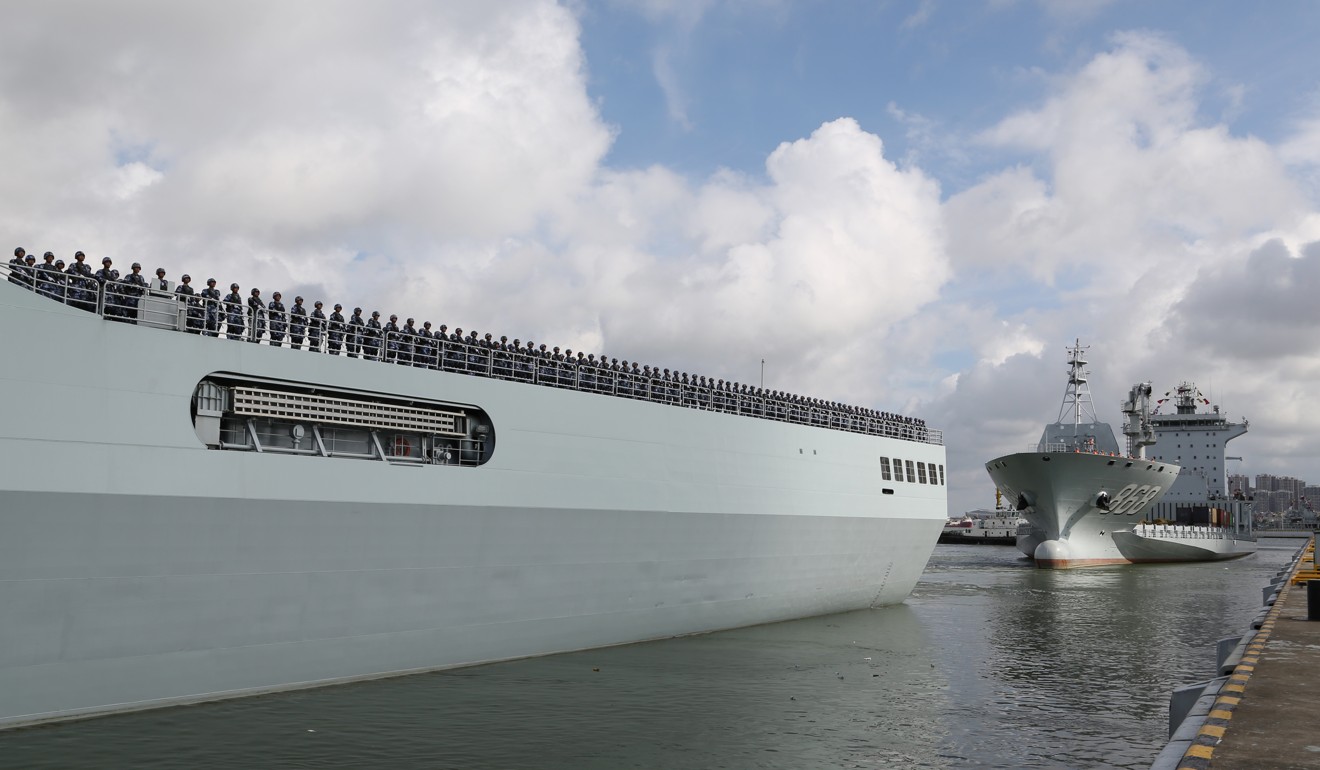

This year China is opening its first military base overseas, a permanent naval port in Djibouti, strategically located at the mouth of the Red Sea. The first troops to man the base left Zhanjiang in Guangdong on ships this month.

Ni said Beijing had become more “open minded” and no longer viewed the dispatch of troops overseas on peace and order missions as an “excuse for imperialist expansion”, but instead as an “obligation of a responsible global power”.

There are currently 2,500 Chinese soldiers stationed in nine regions blighted by war and violence, mostly in Africa, making China the No 1 supplier of manpower for UN peacekeeping missions among the Security Council’s permanent members. The world’s second-largest economy has also committed to covering 10.2 per cent of the UN’s peacekeeping expenditure, second only to the United States.

In addition, Xi promised in 2015 that China would provide another 8,000 peacekeepers for the UN, and help other countries train another 2,000. The new force went on standby last year.

“Chinese involvement is generally welcomed in Africa, and also by the UN, for the PLA is well disciplined and acts fairly and neutrally,” said Hong Kong-based military commentator Song Zhongping. “By contributing to the restoration of peace and stability, the Chinese military has also made a good impression.”

Another example of the Chinese military’s proactive engagement on the world stage was seen last week in the latest “Joint Sea” exercise, when PLA Navy warships joined their Russian counterparts in live-fire exercises in the Baltic Sea for the first time.

China and Russia have held “Joint Sea” naval exercises in other locations every year since 2012, and eight “Peace Mission” counter-terrorism drills since 2005, usually with other members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

Last year alone, the PLA conducted more than 30 bilateral or multilateral joint exercises with both traditional partners such as Russia and Pakistan and Western powers such as the US, focusing on various kinds of military operations.

Since the first Sino-US joint exercise in 2013, the two militaries have practised humanitarian rescue missions together four times, alternating as host. China also took part in the US-led Rimpac exercises, the world’s largest multinational maritime drills, off Hawaii in 2014 and 2016.

Ni said that from a military perspective, joint drills and other cooperative operations helped forces exchange technology, gather information and improve combat capabilities. But like everything else in military diplomacy they also had more political implications, improving ties with friends, showcasing close relationships and sometimes demonstrating power to deter adversaries.

Song said joint operations with the West also facilitated candid communication, increased transparency and revealed each other’s capabilities and red lines so that misjudgments could be avoided, while Zhou added that improved transparency about things such as weaponry development showed the PLA’s growing self-confidence.

Under Xi, China has also been engaging in more frequent and higher-level bilateral and multilateral security dialogues. This year, China and the US elevated military talks via a new diplomatic and security dialogue involving talks between US Secretary of Defence James Mattis and PLA Chief of Staff General Fang Fenghui.

Apart from participating in regional and international mechanisms, Beijing upgraded its own Xiangshan Forum in 2014 into an annual defence and security dialogue, comparable to Singapore’s influential Shangri-La Dialogue.

“China wants to make its own voice heard, and is trying to set its own agenda, in order to make its military stance clear,” Song said.

A particularly difficult but important goal of Bejing’s military diplomacy is to ease concerns about China’s growing military clout – the so-called “China threat” – globally and regionally.

“The stereotype of the PLA had been rigid,” Zhou said. “The Chinese military have to learn and practise how to deal with others and communicate properly, and convince the rest of the world that there is no need to be afraid ... and there is still a long way to go.”

China has become an increasingly assertive actor in the military arena under Xi.

At a military parade at the Zhurihe Combined Tactics Training Base in Inner Mongolia on Sunday, held to mark the founding of the People’s Liberation Army, which is celebrating its 90th anniversary on Tuesday, Xi ordered troops to prepare for battle and defeat “all enemies that dare to offend” their country.

China has also adopted an aggressive posture when it comes to territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

An editorial in Friday’s edition of the Communist Party newspaper Study Times –which is published by the Central Party School – praised Xi for his tough stance on territorial issues with neighbouring countries.

“[Xi] personally steered a series of measures to expand [China’s] strategic advantage and safeguard the national interests,” it said. “On the South China Sea issue, [Xi] personally made decisions on building islands and consolidating the reefs, and setting up the city of Sansha. [These decisions] fundamentally changed the strategic situation of the South China Sea.”

But such moves had cast a negative light on China’s military build-up, said Raffaello Pantucci, director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies in London.

“There is a fundamental disconnect between China’s assertive behaviour in the South China Sea and the Maritime Silk Road [part of the broader Belt and Road strategy that Xi has been championing] which China has not entirely resolved,” Pantucci said.

“On one hand, China is building trust and relations, but on the other it is exacerbating tensions.”

At the end of the day, how Beijing actually uses its power when dealing with disputes – such as the ongoing standoff with India in Bhutan – is what countries around the region are closely watching.

The PLA has shipped troops and equipment into China’s neighbouring Tibet region since the confrontation broke out on June 16, and has conducted a combined force assault exercise on the Tibetan plateau.

A hardline handling of the dispute with India might hurt China’s international image and prompt a backlash, not only from New Delhi but also from countries across the region, warned John Blaxland, professor of international security and intelligence studies at the Australian National University.

“There have been growing concerns around Southeast Asia and Australia that China’s rhetoric of goodwill is not matched by its practice,” he said.