What is the South China Sea code of conduct, and why does it matter?

Foreign ministers from Asean and China are expected to endorse the framework for a code of conduct in the disputed waters on Sunday

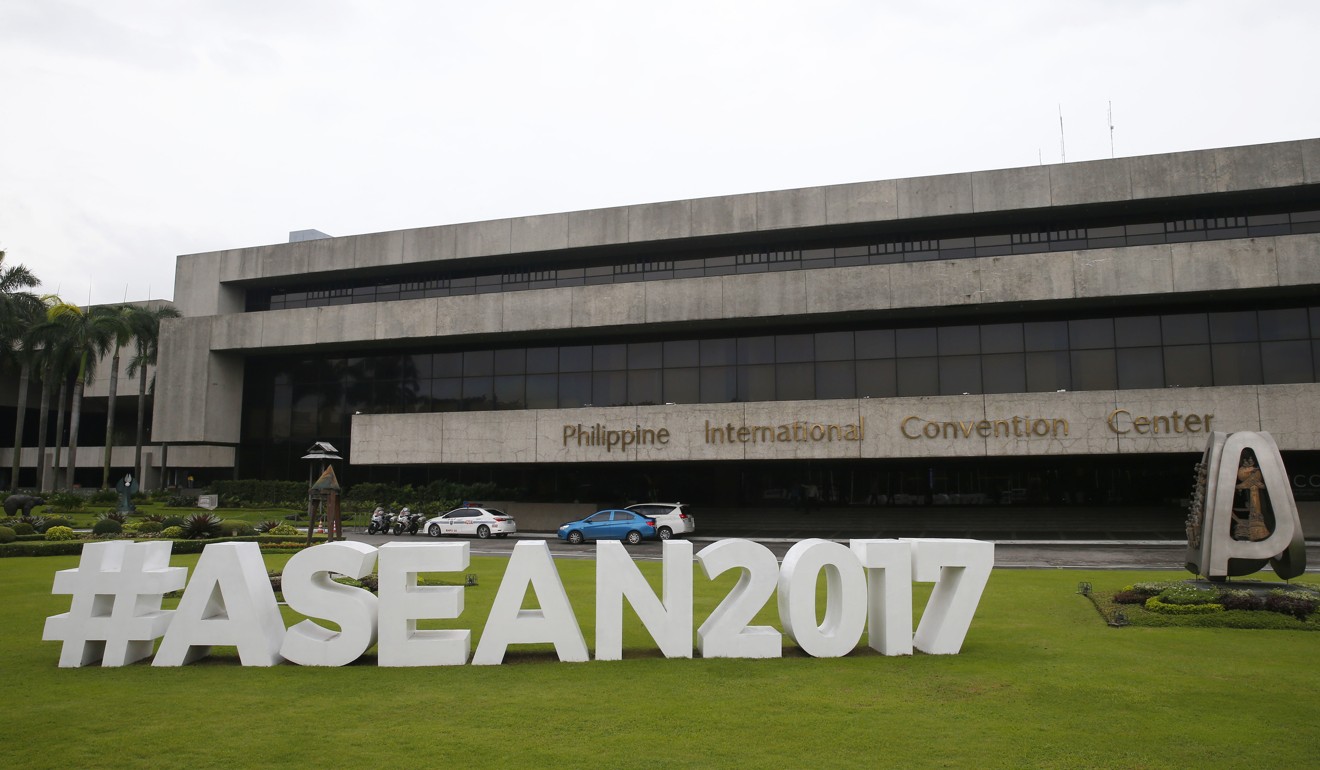

Foreign ministers of the 10 member nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations are gathering in Manila for Asean’s 50th anniversary leaders meeting.

Besides celebrating the organisation’s half century of existence, the parley also brings together top diplomats from non-members such as the US, China, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, India, Russia, Australia, New Zealand and participants in forums such as the Asean Plus Three, the East Asia Summit and the Asean Regional Forum.

The Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs confirmed that foreign ministers from Asean and China would formally endorse the document called “Framework of the code of conduct in the South China Sea,” during their meeting in Manila on Sunday.

What is the code of conduct in the South China Sea?

A code of conduct is a set of rules outlining the norms and rules and responsibilities of, or proper practices for, an individual, party or organisation.

Asean and China agreed to set up a code of conduct in the South China Sea during a 2002 summit amid heightened tensions in the disputed waters. The region in question includes one of the world’s most important shipping lanes, believed to be rich in mineral and marine resources.

But as expectations for an area code of conduct differ between Beijing and the Asean nations, the road to reaching agreement on a set of principles and expectations could be bumpy, observers say.

For Beijing, a code of conduct could be a non-binding instrument that can be leveraged to improve regional trust, rather than resolve overlapping claims; Asean members, however, may have a different opinion, said Zhang Mingliang, a Southeast Asia expert at Jinan University in Guangzhou.

What is to be signed?

The draft framework of the code of conduct was made final at an Asean and China senior officials meeting in May in southwestern China’s Guizhou province.

Details about the framework’s content have not been released to the public since. The Chinese foreign ministry has said this non-action could keep outside interference away. It did not name the US, whose Asia Pacific policy has remained partially fuzzy since US President Donald Trump took power in January, triggering widespread concern among Southeast Asian nations.

In May, Singaporean Foreign Minister Chee Wee Kiong said the draft framework had “positive momentum” and that he hoped to make “steady progress toward a substantive code of conduct”.

A draft of the text leaked by the media describes the envisioned agreement as “a set of norms to guide the conduct of parties and promote maritime cooperation in the South China Sea”. It is “not an instrument to settle territorial disputes.”

Regional experts and diplomats believe the agreement’s framework will be more symbolic in content than substantive.

“Many principles, such as peaceful solving disputes, have been approved by different parties even without the framework,” said Zhang Mingliang of Jinan University.

Robespierre Bolivar, a spokesman for the Department of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines, told reporters in Manila on Tuesday that the framework would be an outline. He did not specifically mention the arbitration decision in which The Hague’s Permanent Court ruled against China’s territorial claims and its massive reclamation activities in the region.

A brief history of a code of conduct in the South China Sea

The concept of a code of conduct was first raised in the 1990s; but it was not until 2002 at a gathering of foreign ministers from Asean countries and China in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, that a code of conduct was mandated by the non-binding China-Asean Declaration on Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea.

Since then, little progress on a code of conduct has been made while tensions have intensified as reports of fishing disputes in the area grow commonplace.

It was not until 2013, when Beijing, in an apparent attempt to ease its tensions with its Southeast Asian neighbours, agreed to begin formal consultation on the code of conduct.

And it took almost four years for senior officials from China and the Asean nations to agree on a framework for the code of conduct, though the framework’s contents remain unreleased to the public.

What’s next?

As the host of this year’s Asean summit and as a key claimant state in the South China Sea territorial disputes, the Philippines has said it will push for starting discussions on the actual code of conduct as soon as the Framework-COC is officially endorsed on Sunday.

However, prospects for the parties reaching agreement on a real code of conduct remain dim.

For Asean, the challenge will be getting all 10 members to come to a unified viewpoint on the South China Sea issue; meanwhile, Beijing, which has been growing more assertive on maritime issues, is unlikely to step back over its sovereignty, which it calls a core national interest.

In an interview with ABS-CBN News, Medardo Abad Jr., the former chief of the Asean Regional Forum, said that obtaining a commitment from the stakeholders not to militarise the disputed area should be included in the framework.

Finally, signs of renewed tensions in the South China Sea have reemerged in recent months.

Vietnam, also a member of Asean, has been oil drilling in disputed waters claimed by China since June, and China has built a cinema on Woody Island in the Paracels, which are also claimed by Taiwan and Vietnam.