Why Chinese investors are struggling to gain a foothold in Tajikistan

Central Asian country is one of first stops on ‘Belt and Road’, but legal difficulties, murky politics and security concerns pose obstacles to business

Chinese businessmen in Tajikistan are finding that life on the “Belt and Road” is not all beer and skittles – sometimes it’s more like pigeons and shotguns.

The head of the Federation of Overseas Chinese in Tajikistan, Hu Feng, explained the problem recently on a hot, dry day in the Tajik capital Dushanbe.

“You know how Tajik shoot pigeons?” he asked. “ They scatter some food on the ground and then wait around the corner with a shotgun. When pigeons come, they just blast away from a short distance. That’s the dire situation facing Chinese businessmen here.”

Hu has lived in Tajikistan for a decade, has a Tajik wife and has provided help to dozens of Chinese investors in Central Asia. His metaphorical Chinese pigeons are the investors, inspired by President Xi Jinping’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, who flocked to the former Soviet republic, perched on China’s western border, in search of their fortunes.

Encouraged by the Belt and Road trade and infrastructure development plan, Chinese investment in Tajikistan rose 160 per cent year on year in 2015 to US$273 million, comprising 58 per cent of the country’s investment inflow that year.

According to Tajikistan’s statistics agency, total Chinese direct investment in the country had topped US$1 billion by the start of October last year, eclipsing Russian direct investment.

Zhejiang businessman Zhu Bailin, 53, was one of those motivated to invest in Central Asia after President Xi Jinping proposed the Belt and Road Initiative during a visit to Astana, the capital of Kazakhstan, in September 2013.

A year later, Zhu’s Zhejiang Congcai Heavy Machinery Manufacture invested US$25 million for a 60 per cent stake in the Taj-China 2013 cement factory in Vahdat, a city 10km east of Dushanbe, with the other 40 per cent owned by Tajik partner Kodirov Abduhalim Addukarimovich.

Hu told the South China Morning Post that having a Tajik partner was not a legal requirement but was a common practice for Chinese investors because it could improve communication with different government departments.

“The Tajik partners are often powerful locals, and some big Chinese projects would prefer to partner with people with ties to Tajikistan’s president,” he said.

Zhu said the factory began production in 2015, but Addukarimovich later sought total control over it. In September last year, Tajikistan’s State Committee for National Security asked representatives of the Chinese shareholders to attend a meeting at its headquarters, Zhu said, adding that they were threatened with the use of force if they did not comply.

He said he had since reached a compromise with Addukarimovich, who had agreed to lease the factory for US$454,000 a month. However, he was only receiving about a third of that amount.

“I am seriously wondering whether legal means can solve my problem or not, since he still continued to send me around one million yuan a month,” Zhu said. “He might stop giving me money forever if I sue him.”

Zhu, who has since returned to Zhejiang, said: “If I could go back in time, I would definitely not choose to invest in Tajikistan.”

Kodirov Muhhammadi, a spokesman for the cement factory, denied Zhu’s allegations and accused him of installing obsolete machinery that made production inefficient and caused lots of pollution.

Two earlier investors in Tajikistan also tell cautionary tales.

Joseph Chan Nap-kee, the chairman of Hong Kong-listed Kaisun Energy, said it was difficult to challenge rulings by the Tajik authorities in the country’s courts.

He said Kaisun was charged more than twice the profits tax it expected after agreeing in 2012 to sell a 52 per cent stake in a Tajik prospecting and mining company to a company from China’s Xinjiang region for HK$394.64 million (US$50.53 million).

“The US$20 million profit tax was ridiculous, but it was difficult for us to find a lawyer in Tajikistan that could defend the company in court,” Chan said. “From the Tajik local court to the highest court, we lost all the way. They all supported their national government.”

According to the World Bank, Tajikistan’s profit tax is 17.7 per cent, which would make Kaisun’s tax liability from the deal US$8.94 million.

Chan, who is also chairman of the Hong Kong-based Silk Road Economic Development Research Centre, remains cautiously optimistic about business prospects on the Belt and Road but said Kaisun had to find a Russian lawyer to represent it because Tajik lawyers risked losing their licences if they took on a case opposing the government.

Meanwhile, Kelimu Abudureyimu, a 53-year-old businessman from Xinjiang, found recourse to diplomatic channels equally fruitless in a commercial dispute.

He and four Chinese partners bought a fluorite and tungsten mine 40km north of Dushanbe from a Russian businessman, securing total control in 2012, but a Tajik court ordered its confiscation by the government in late 2014, saying the 2005 auction that led to its acquisition by the Russian had not followed proper procedures.

By that stage, the Chinese partners, having built an 18km road to the mine, dug a tunnel extending more than 1km and set up a processing plant, were about to begin production.

Abudureyimu said he felt he had been fooled by the Tajiks and the Russian, and asked for help from the Chinese embassy in Tajikistan and China’s State Council.

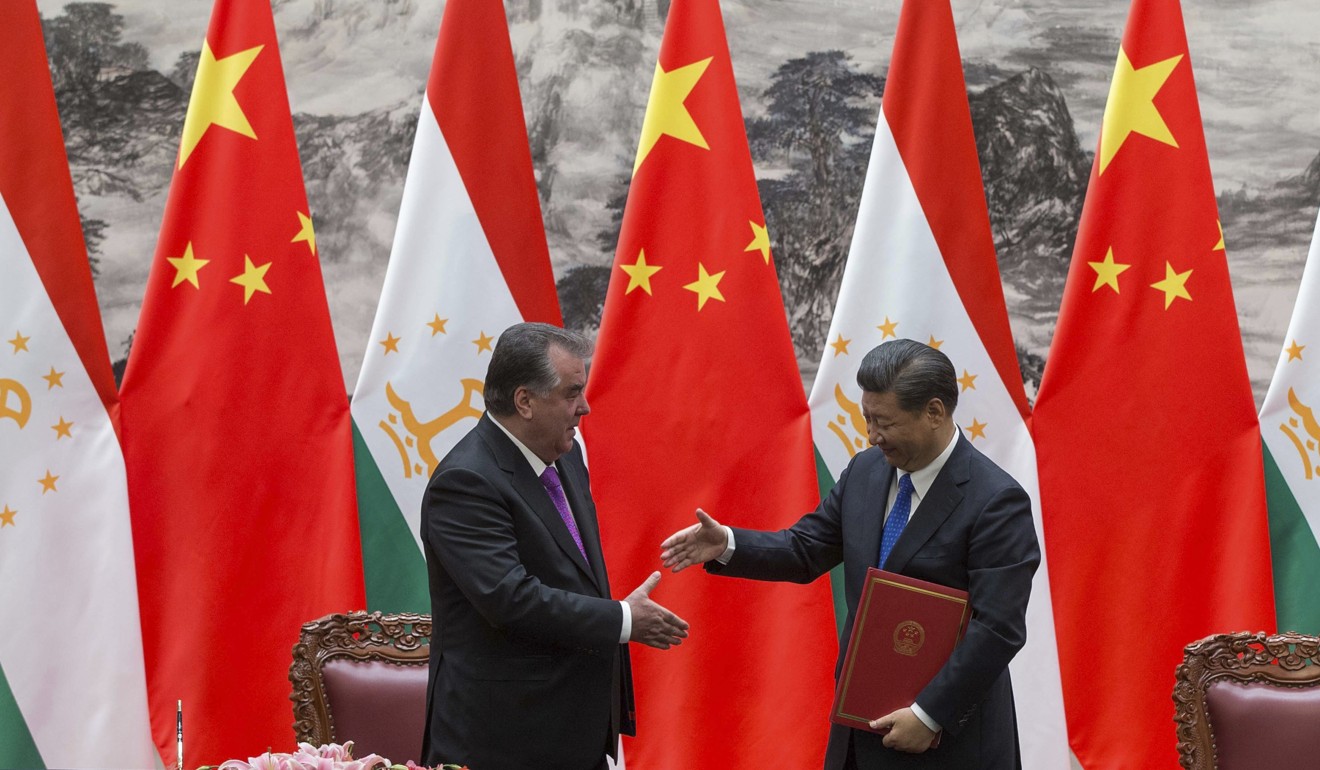

But in July 2015, a Presidential Decree from Tajik President Emomali Rahmon endorsed the court ruling and ordered that management rights be transferred to Tajik Aluminium, Tajikistan’s chief industrial asset, which some overseas media reports have said is personally overseen by Rahmon.

Tajikistan’s Presidential Office failed to respond to repeated inquiries about the case from the Post.

Even companies that have teamed up with the Tajik government on successful projects have run into problems.

JV Zeravshan, a joint venture 75 per cent owned by China’s state-owned Zijin Mining and 25 per cent owned by the Tajik government, runs two gold mines in Tajikistan that have created more than 2,000 jobs.

But its general manager, Zhang Shunjin, said JV Zeravshan failed to buy another gold mine last year, because it valued the mine at 300 million to 400 million yuan but the Tajik government asked for US$500 million.

“That’s because Tajikistan has an illusion of floods of Chinese investors prompted by the Belt and Road Initiative and thinks highly of itself,” Zhang said.

Liu Chuanwu, a former Chinese diplomat who used to be in charge of economic matters in Central Asia before he founded the Xinjiang-based business risk consultancy Huahe International, said most Chinese investments in Central Asia, especially those involving joint ventures, failed.

“Many of them invested in Central Asia before clearly knowing the market risks and its unique environment,” Liu said. “They hoped to solve economic and legal problems by building up a good relationship with local or national officials. But when true problems come, governmental officials cannot help them, and instead, prey upon them.”

Deirdre Tynan, Central Asia project director at the International Crisis Group, a Brussels-based NGO, said investing in Central Asia could be fraught.

“The rule of law is flimsy and corruption is rampant,” she said. “This has put off many potential Western investors for a long time, and Chinese firms now encounter the exact same difficulties.

“There is little small to medium-sized Chinese companies can do. But the international community including China and Russia, should push for better practices from the Central Asian governments and, where necessary, fund and support reforms.”

Transparency International’s 176-country Corruption Perceptions Index last year ranked four Central Asian countries – Kyrgyzstan (136), Tajikistan (151), Turkmenistan (154) and Uzbekistan (156) – in the bottom quartile, with Kazakhstan (131) just scraping into the third. China ranked 79th.

Pan Zhiping, head of the Central Asian Studies Institute at the Xinjiang Academy of Social Science, said the biggest problem in Tajikistan was that it was too poor to have effective checks and balances and a functional legal system.

Central Asia is not like developed Western countries that have clear accountability mechanisms,” Pan said. “Tajikistan’s legal system is under development; its officials and citizens do not have a strong awareness of law. Thus, in this sense, the problems that Chinese companies have experienced are inevitable. Governmental communication should be enhanced. But there is a long way to go to reach a better stage.”

Although difficulties abound, Professor Nuralizoda Amrullo, an economist at the Finance and Economics Institute of Tajikistan, said he was very optimistic about future cooperation between China and Tajikistan, especially under the Belt and Road Initiative.

“China and Tajikistan share thousands of years of history,” he said. “We hope that, in the future, economic development will be even better.”

Tajikistan’s Ministry of Foreign Ministry also said it was confident that cooperation would grow.

“It is believed that in the future, there will be increased attention of Chinese investors to Tajikistan’s investment opportunities and joint ventures and the trade relations between two neighbouring countries and friends will be strengthened,” it said.

One private Chinese company that shares that optimism is Lihua Cotton Industry, from Xinjiang, which owns 70 per cent of a joint venture set up with Tajik partner Valiev Firdaus Sirjovich.

The Vodii Zarrin Agrarian Alliance is currently growing cotton on 100 square kilometres of land in southern Tajikistan and has plans to expand to 240 square kilometres.

While it has yet to make a profit, company spokesman Xu Jie said he was optimistic about the future because of Tajikistan’s plentiful sunshine and land, its cheap labour and low-interest loans offered by Agriculture Bank of China.

Beijing’s concerns about separatism in Muslim-majority Xinjiang affect its relations with its neighbours in Central Asia, where Islam is the dominant religion and the extremist threat appears to be growing.

The International Crisis Group estimates 2,000 Central Asians joined the Islamic State militant group, which has recently been losing territory in Syria and Iraq, while Russian estimates put the figure at around 4,000.

“We have contacted Chinese embassy many times, but Beijing does not have a very good solution,” Zhu said. “Embassy officials told me several times that China’s relations with Tajikistan mainly focus on antiterrorism cooperation, so the economic loss is not a major concern.

“Thus, for the sake of better antiterrorism cooperation, China has to sacrifice its economic interests a little.”