Why China’s not glad US-Pakistan ties have hit a rough patch

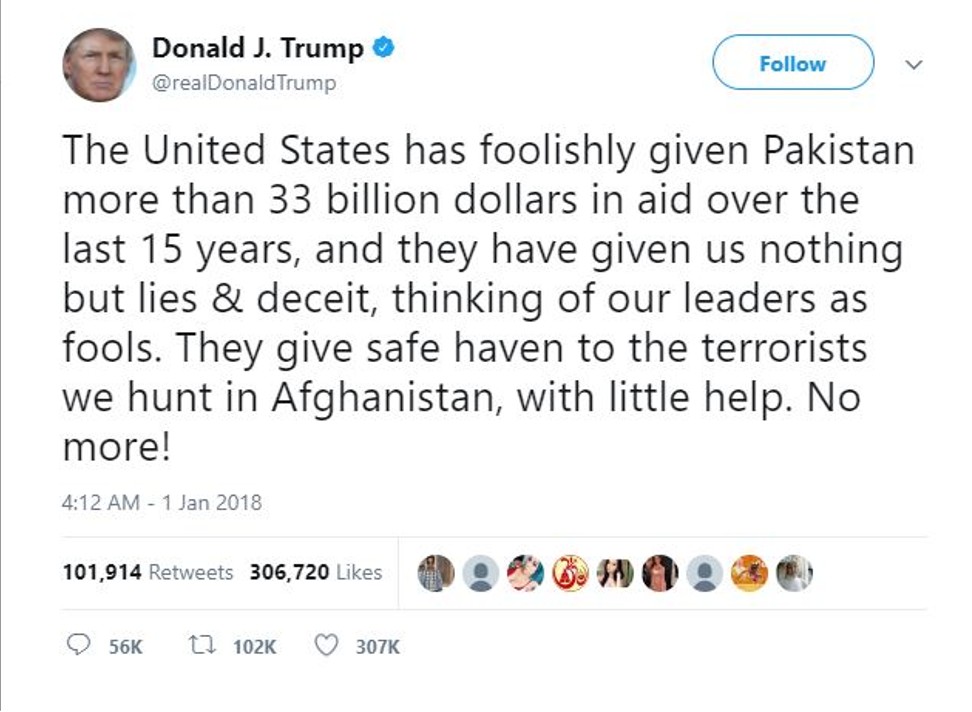

Donald Trump opened new year with a tweet accusing Islamabad of ‘lies and deceit’

Barely a week into the new year, it appeared 2018 might become the worst year for US-Pakistan ties since 2011. That year, not only did a Central Intelligence Agency contractor shoot dead two Pakistanis, sparking a diplomatic crisis, but the United States also carried out a covert operation to kill Osama bin Laden on Pakistani soil without the knowledge of the Pakistani military.

More than any other year in the past decade, 2011 illustrated the extent to which the fundamental national interests of the US and Pakistan diverged sharply – on everything from Afghanistan to the utility of terrorism as an instrument of state power in South Asia.

Of course, this observation is not particularly novel or exciting. US presidents have known it for some time. In 2009, when former US president Barack Obama delivered his first speech on America’s war in Afghanistan – what is today the US’s longest war – he criticised Islamabad for providing safe haven to extremists and militants.

Little had changed in eight years. In August, when US President Donald Trump delivered his speech on Afghanistan strategy, he too criticised Islamabad. “It is time for Pakistan to demonstrate its commitment to civilisation, order, and peace,” he said.

Bilateral ties got off to a rocky start this year when Trump fired a Twitter broadside at Pakistan at 4.12am on January 1. “The United States has foolishly given Pakistan more than 33 billion dollars in aid over the last 15 years, and they have given us nothing but lies & deceit, thinking of our leaders as fools,” he tweeted. “They give safe haven to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan, with little help. No more!”

His words were swiftly translated into policy. The US announced that it would withhold more than US$1 billion in aid to Pakistan by suspending a US$255 million tranche of aid under the foreign military financing programme and at least another US$900 million in coalition support funds reimbursement.

Again, none of this was new: the Obama administration too had withheld aid from Pakistan in an effort to condition the country’s fundamental preferences. It failed and the Trump administration likely will too. Pakistan has long been prepared for precisely such an eventuality, recognising the partnership with the US for what it is: a tenuous alliance. Islamabad also has no shortage of ways in which it might retaliate, including by blocking US supply routes to Afghanistan, where the Trump administration decided to pursue a minor troop surge.

However US-Pakistan relations progress from here, it would be a mistake to presume that China is glad to see a deterioration in the relationship between Washington and Islamabad. While much of the Trump administration’s action and inaction elsewhere has coincidentally had the effect of abetting Chinese ambitions – for example, in Southeast Asia – nothing could be further from the truth in Pakistan.

For years, the US has been aware of the close relationship between Beijing and Islamabad, one that the two countries refer to as an “all-weather partnership”. While China is aware of Pakistan’s use of terror groups as proxies in Afghanistan and India, it won’t be glad to see US aid to Pakistan dry up.

First, even as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor gains steam, it is important not to conflate what Pakistan gains from China with what it gains from the US. Both states provide important assistance to Pakistan, but in different ways.

Second, a broader decline in Pakistan-US relations could lead to the US attempting to influence China’s relationship with Pakistan. Beijing has a broad and difficult agenda with the US already, with areas of contention ranging from the South China Sea to the Korean Peninsula. Having its activities in Pakistan come under US scrutiny would be unwelcome.

Finally, Beijing no doubt understands the geopolitical limitations a sufficiently close US-Pakistan relationship poses for US freedom of manoeuvre with regard to India. While ties between New Delhi and Washington have grown increasingly untethered from America’s attitude towards Pakistan since the mid-2000s, Indian scepticism persists.

While many in India have applauded the Trump administration’s moves on Pakistan recently, there remain those who are sceptical of the enduring value of what might end up being just another road bump in a long relationship. For China, ensuring that the US sustains a balanced relationship with both Pakistan and India can be a way of ensuring that Washington does not veer too far into an anti-China entente with India (even if the prospect of a US-India alliance remains far from reality).

It remains to be seen where this latest schism between Washington and Islamabad might lead. Unlike in the past, the US may choose to tap harsher policies to punish Pakistan, including targeted sanctions against individuals in the Pakistani military and intelligence services. China will no doubt be watching closely – more out of self-interest than out of concern for its all-weather partner.

Ankit Panda is a senior editor at The Diplomat