Five things to watch for during British Prime Minister Theresa May’s China visit

Trade tops leader’s agenda on her first official visit to China, accompanied by a delegation of 50 business leaders

When British Prime Minister Theresa May begins her three-day visit to China, her main focus will be on evaluating opportunities to expand the trading relationship between Britain and China as the latter opens up its markets.

After starting the tour on Wednesday in the central city of Wuhan, May’s trip shifts to Beijing where she will meet top Chinese leaders. Her visit concludes with a stop in Shanghai.

May’s trip comes as Britain’s prospective withdrawal from the European Union after the stunning “Brexit” referendum is seen as giving London more flexibility to set trade deals with China. On that note, May is travelling to China with a delegation of business leaders representing a broad range of sectors.

Here are five things to watch for during May’s trip:

Can May shift the “golden era” between China and Britain into a higher gear via economic cooperation?

In a statement ahead of her trip, May said her visit would “intensify the ‘golden era’ in UK-China relations.

“The depth of our relationship means we can have frank discussions on all issues,” the prime minister said.

“There are huge trade opportunities in China that we want to help British businesses take advantage of.”

President Xi Jinping used the term “golden era” to describe relations between China and Britain during his state visit in 2015. A highlight of that trip was the two sides signing deals worth £400 billion (US$565.45 billion).

A delegation of more than 40 business leaders is accompanying May. Members represent such blue-chip public companies as BP, HSBC, Inmarsat, Standard Chartered, Sirius Minerals, Standard Life Aberdeen, AstraZeneca and the London Stock Exchange Group.

Even fewer signings this time around would be a step forward for two countries whose economic ties were bruised by Britain’s decision to quit the European Union. China’s goal had been to make London a gateway to the broader EU, according to Wang Yiwei, a Beijing-based European issues specialist.

British trade with China has surged 60 per cent since 2010, and last year, with the world adjusting to the Brexit vote after its initial shock, Britain’s China-bound exports jumped 30 per cent.

For its part, China remains interested in investing in British assets, particularly in high-profile infrastructure projects such as the Hinkley Point nuclear power plant on the Bristol Channel coast of Somerset, England.

China, through state-owned China General Nuclear Power Corporation, owns a third of the project, which May’s government has said reflects Britain’s openness to foreign investment.

China also is eyeing a potential British high-speed rail contract as part of its global push.

“Unlike the EU and the US, the UK has not signalled any meaningful toughening of foreign investment screening and the door is very much open to foreign investors,” said Tim Gee, a partner with London law firm Baker McKenzie.

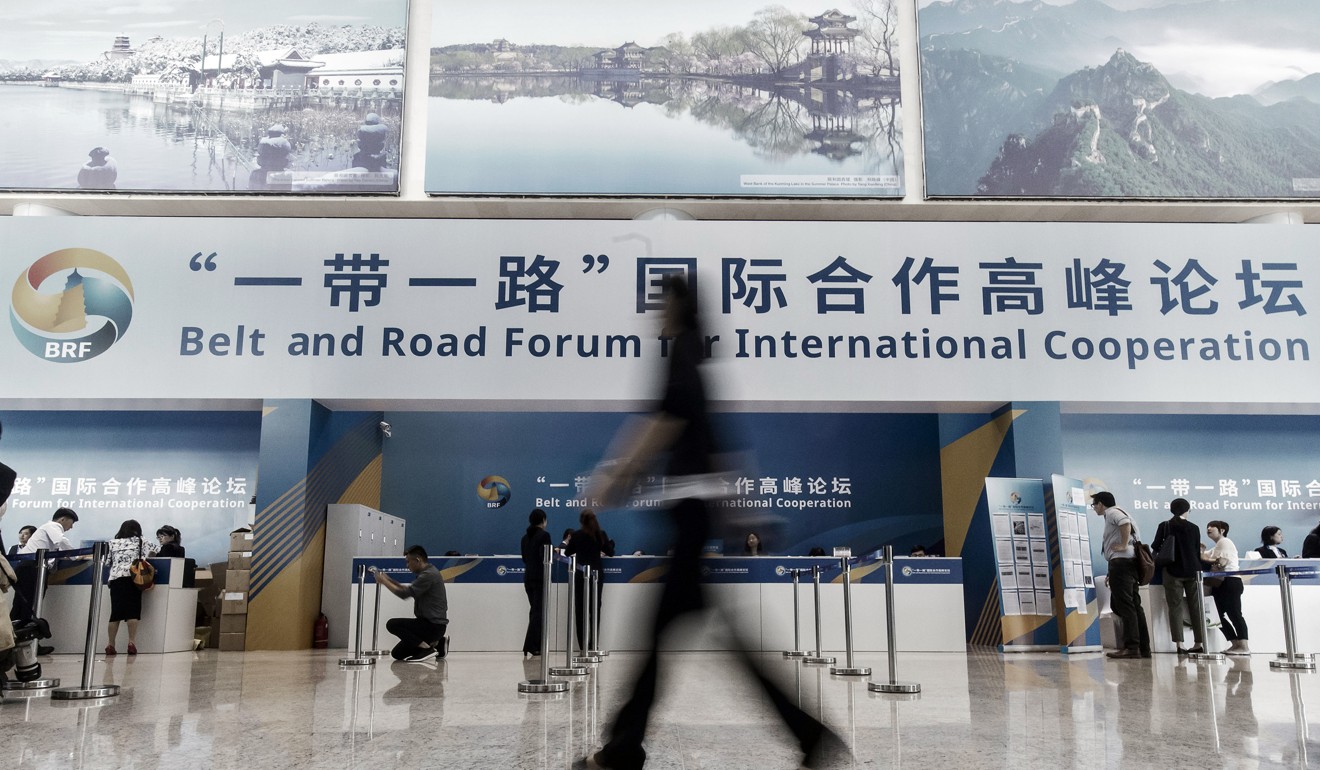

Will May endorse Beijing’s massive belt and road infrastructure programme?

A priority for Beijing during May’s visit likely is getting Britain’s formal endorsement of Xi’s signature programme, the “Belt and Road Initiative”, which aims to increase China’s trade and infrastructure links to Asia and beyond.

“If Prime Minister May is smart enough she would know what China wants to hear from her the most is the support of the belt and road,” said Jin Canrong, a Renmin University international relations scholar.

May last year sent Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond to attend Xi’s Belt and Road Forum a few weeks before Britons went to the polls in a general election. Later that year Hammond said Britain would appoint a special envoy to handle belt and road-related issues and form a Belt and Road Council of senior British business leaders who were interested in the plan’s infrastructure initiatives.

May’s office has refused to confirm whether the prime minister would formally endorse belt and road, reflecting the pressure she faces from the administration of US President Donald Trump who has labelled China a strategic competitor, the Financial Times has reported.

Britain’s ambassador to Beijing, Barbara Woodward, told reporters on Monday that in line with the vision of a “global Britain” May articulated at the World Economic Forum at Davos last week, Britain saw itself as a “natural partner” in the “Belt and Road Initiative”.

Britain’s companies and financial institutions have shown they are keen to bring “international standards” to the China-backed projects, Woodward said.

Britain was the first major Western country to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, an important finance organ formed to support belt and road projects, the ambassador said.

Will May raise Hong Kong’s concerns with Beijing?

It is not clear if May’s promise of “frank discussions on all issues” includes emphasising to the Chinese leadership that Britain’s former colony of Hong Kong faces growing threats to “basic freedoms, human rights and autonomy”, as Chris Patten, Hong Kong’s last British governor, told May in a letter.

Patten wrote that he wanted May to speak up on behalf of Hong Kong on topics including the enforcing of mainland law at a cross-border railway’s Hong Kong terminal; local authorities’ denial of Hong Kong entry for British human rights activist Benedict Rogers and Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s comment that a damning report by Patten’s fellow British peer Paddy Ashdown, a co-founder of the London-based Hong Kong Watch group, raising concerns about the city’s rule of law amounted to “meddling” in China’s and Hong Kong’s affairs.

Wang Yiwei, the European issues specialist, said it would not surprise the Chinese side to hear May raise Hong Kong’s issues but the talk would be unlikely to go anywhere.

“Hong Kong has always been a topic of the conservatives and there can hardly be any compromise on this as one of their basic values,” Wang said.

What is May doing in Wuhan and Shanghai?

On the one hand, Wuhan’s inclusion on May’s itinerary seems surprising. The city rarely has been a destination of visiting foreign leaders. One exception was former French President Jacques Chirac’s 2006 visit to a Franco-China joint car factory.

But the capital of Hubei province is home to 85 colleges and more than 1 million students. That makes it an important educational hub in China and attractive to the British education sector, which is represented in May’s delegation.

Her entourage includes a representative from the University of Manchester, based in Wuhan’s sister city of Manchester, England.

There are 160,000 Chinese students in Britain.

How high on May’s agenda is North Korea?

As fellow permanent members of the UN Security Council that has imposed punishing sanctions on North Korea over its nuclear provocations, Britain and China have a growing number of common interests, according to Woodward.

They also have numerous potential collaboration opportunities. In that regard, North Korea’s nuclear programme and UN sanctions, the Winter Olympic Games in Pyeongchang County, South Korea and climate change are on the agenda for May’s China visit.

China and Britain both could benefit from collaborating to halt terroristic activity by Islamic State fighters and other hostile groups in hotspots such as Afghanistan and Pakistan. They also could profit from working together to counter human-trafficking and jointly strengthening aviation security against terrorism.

The two nations also could reap benefits from teaming up to combat the illegal manufacture and distribution of the pain medication fentanyl from China.

Trump has claimed that fentanyl from China, which recreational drug users often mix with heroin or cocaine, has “flooded” the West.