Could a China-Philippine joint development deal be the way forward in the South China Sea?

An agreement on offshore oil and gas exploration could pave the way for greater cooperation across the disputed waterway, Richard Heydarian writes

In a remarkable reflection of the blossoming Philippine-China relationship, the two neighbours have signalled their commitment to sharing contested resources in the South China Sea. Both are determined to ensure common interests, rather than disputes, define the overall texture of their relationship.

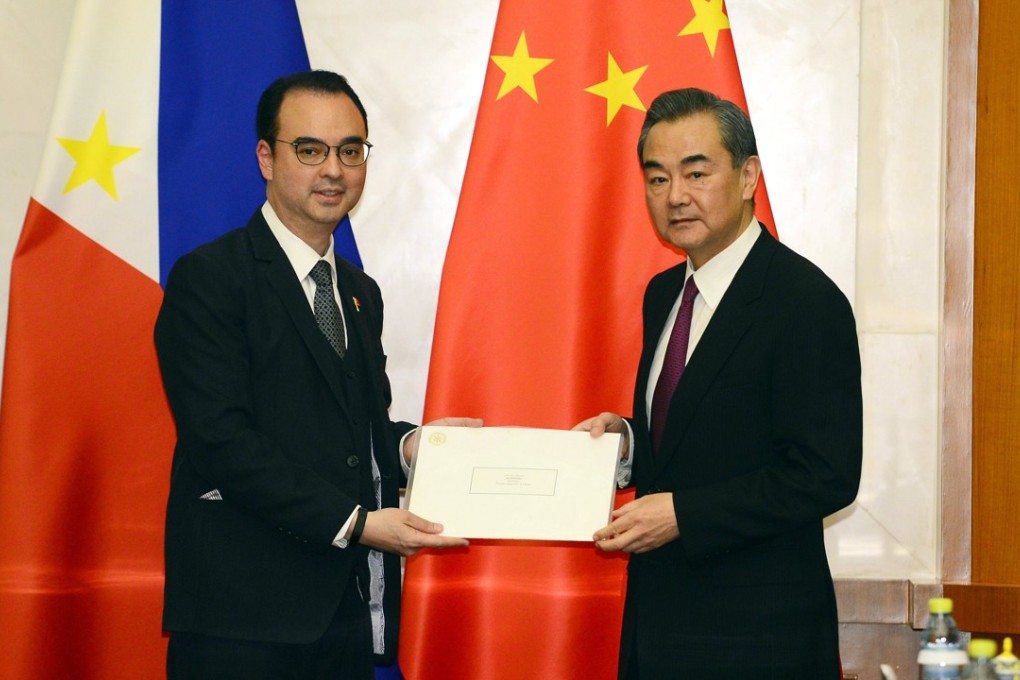

During his recent visit to Beijing, Philippine Foreign Secretary Alan Peter Cayetano raised the prospect of a joint development agreement (JDA) with China.

Hailing a “golden period” in relations, he expressed Manila’s wish that “South China Sea disputes will no longer block the development of bilateral ties” but instead, “be turned into a source of friendship and cooperation between our two countries”.

His Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, said the two neighbours were considering a JDA “in a prudent and steady way” to “advance cooperation on offshore oil and gas exploration”. If successful, a Philippine-China JDA could pave the way for a broader set of cooperative arrangements across the South China Sea basin.

What is at stake is the effective and peaceful management, if not permanent and just resolution, of one of the most intractable and high-stakes maritime disputes of the 21st century. In the meantime, however, the Philippines and China will have to overcome significant legal and political hurdles in their quest for a “win-win” solution.