Spy risk or cultural asset? The divide over China’s Confucius Institutes on US campuses

The debate over the language and culture centres has become a testing ground for the American response to China’s growing global reach

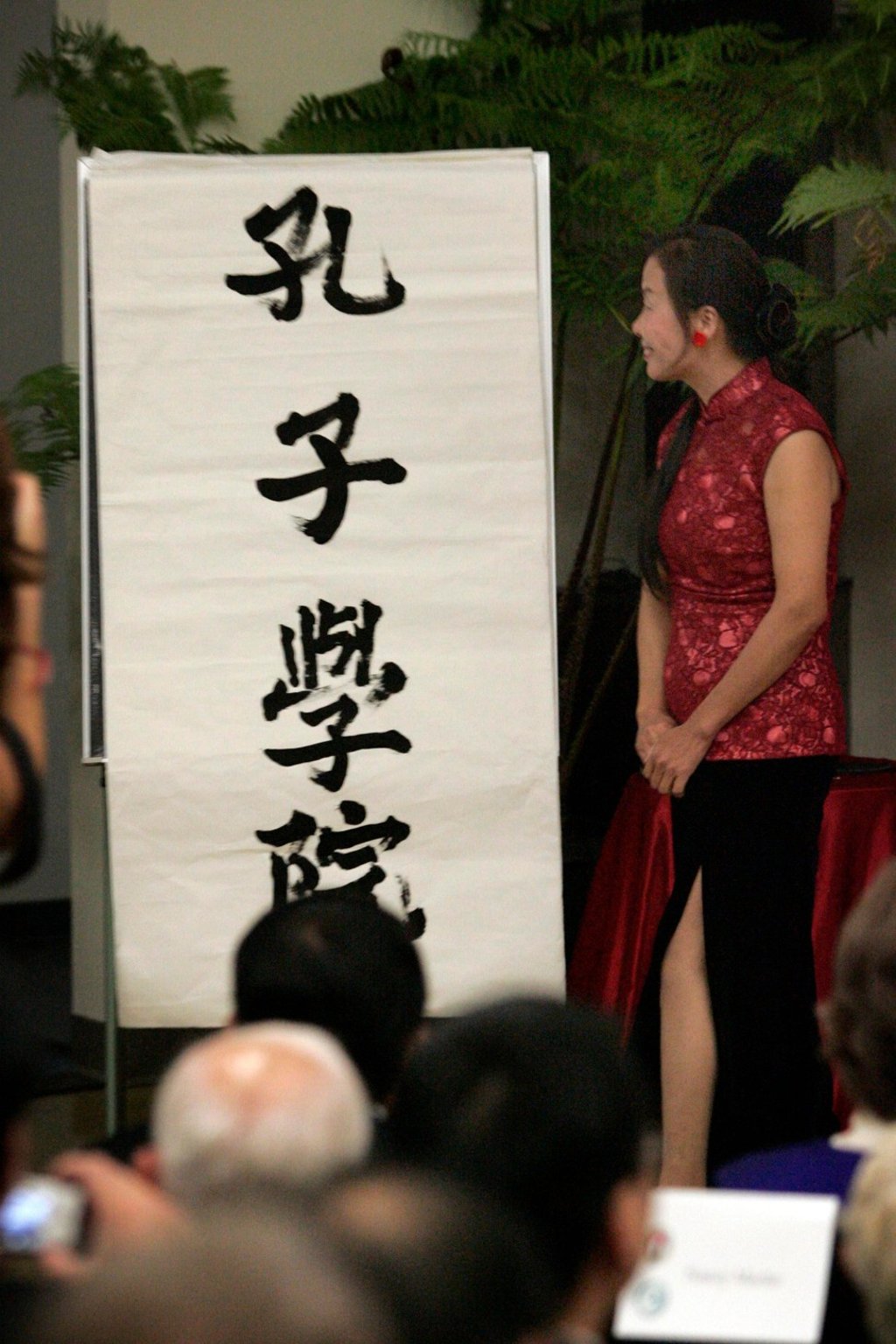

On college campuses in virtually every state across the United States, the Chinese government supports more than 100 institutes that teach language and culture. For university students like Moe Lewis, they offer a chance to learn about Chinese art and pick up a few phrases in Mandarin. For critics, like Republican Senator Marco Rubio, they present a threat to academic freedom and a spy risk.

As tensions between the US and China rise over trade and security, perceptions vary wildly about educational exchanges that have thrived since diplomatic relations were normalised four decades ago.

Increasingly, US authorities are concerned that Chinese professors and students could exploit access to universities to gather intelligence and sensitive research – an issue a Senate judiciary panel will address on Wednesday.

And while the China-funded Confucius Institutes that have mushroomed worldwide since 2004 focus on benign subject matter, US lawmakers are pushing for them to be more tightly regulated or even closed down.

“I think every college should be aware of what these institutes are used for and that they are in fact consistently been used as a way to quash academic freedom on campus at the behest of a foreign government,” Rubio said. “I would encourage every college in America to close them. There’s no need for these programmes.”