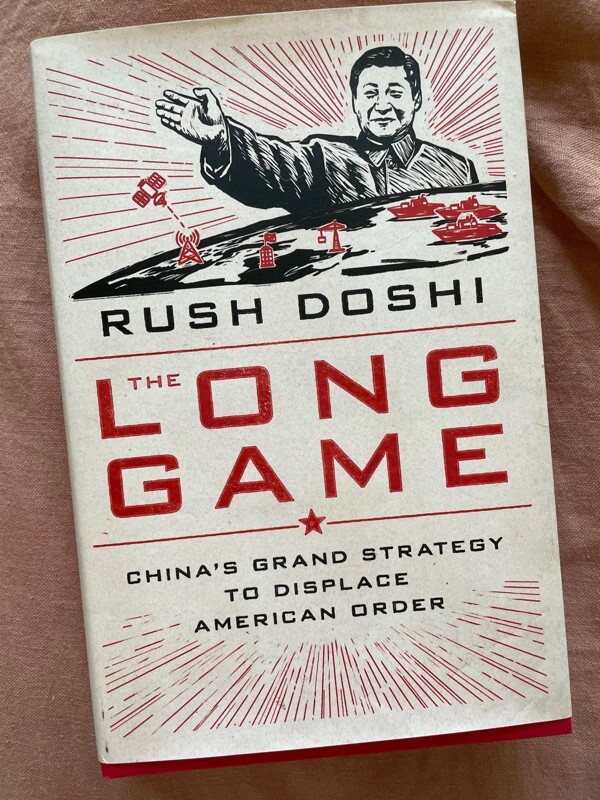

China-US relations: is Beijing working a ‘long game’ to replace America as dominant world power?

- New book by Rush Doshi argues that, in the wake of Brexit, the election of Trump and the pandemic, China has been building foundations for its own world order

- China does not want to fall into a spiral of conflict but at the same time does not fear confrontation on core issues, says Chinese analyst

China and the US have been at loggerheads on almost all fronts, but with tensions continuing into the Joe Biden presidency, where is the relationship heading? After US deputy secretary of state Wendy Sherman’s visit to Tianjin last week, and the Washington debut of China’s new envoy to the US Qin Gang, this series aims to check the temperature of bilateral relations. In this article, Sarah Zheng looks into how the US sees Beijing’s efforts to build up its own world order.

Democrats and Republicans may well agree on one thing – that China wants to displace the United States in the global order.

China takes pointers from Mao in protracted power struggle with US

“It is clear, then, that China is the most significant competitor that the United States has faced and that the way Washington handles its emergence to superpower status will shape the course of the next century.”

Beijing will not engage in intense ideological war with the US: expert

In a Foreign Policy piece last December, Doshi and Campbell rejected anxiety about the US’ decline, calling for a constructive China policy under Biden that strengthened the US at home and made it more competitive abroad in a way that “need not require confrontation or a second cold war”.

In reviewing Doshi’s book, Georgetown University political scientist Michael Green said “the debate over whether China has a strategy to displace American leadership is over”.

However, Chinese scholars argue that Doshi’s view of a grand strategy from China dating back to the late 1980s is a stretch. But, regardless of how long or how extensive Beijing’s strategic ambitions have been, it is less relevant than the fact that this view has become the political consensus in Washington – one that will inform a more hardline strategy for both the US and China going forward, they say.

The practical steps that Doshi, a former director of the Brookings China Strategy Initiative, advocates in his book already mirror Biden’s current approach of leaving the era of engagement with Beijing behind, in favour of strategic competition with a country they now see as their primary threat. For Beijing, the message from the US is increasingly clear: expect stormy waters ahead.

There are echoes of hawkish Trump adviser Michael Pillsbury’s warnings of Beijing’s grand ambitions in The Hundred-Year Marathon as Doshi’s book details how China’s strategic efforts in recent years have been the most assertive phase in a decades-long strategy to displace the US, dating back to the end of the Cold War.

Good timing is key to China’s manoeuvres in a post-Trump world order

Drawing extensively from Chinese Communist Party primary source documents, Doshi argues that the first phase of China’s grand strategy, from 1989 to 2008, was to quietly engage in “blunting” – his term for efforts to diminish a state’s power to regulate the behaviour of other states – of American power, particularly in Asia.

This was followed by China’s efforts to begin “building” – establishing its own forms of control over other states – the foundation for regional hegemony in Asia, after perceiving US weakness in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis.

“In this period, the Chinese Communist Party reached a paradoxical consensus: it concluded that the United States was in retreat globally but at the same time was waking up to the China challenge bilaterally,” Doshi writes.

China’s vision of its global order, key to its articulated goal of “national rejuvenation” by 2049, would be one that would “erect a ‘zone of superordinate influence’ in its home region” and “partial hegemony” across developing countries along the belt and road, he says.

Doshi posits that the US, in response, needs to adopt an asymmetric strategy to undermine Beijing’s displacement efforts rather than compete “dollar-for-dollar, ship-for-ship, or loan-for-loan”.

At the same time, the US would need to rebuild its foundations for power and order, including by ensuring continued US dollar dominance, reinvesting in US innovation, maintaining a diverse US military posture in the Indo-Pacific and building allied coalitions.

“US-China competition is primarily a competition over who will lead regional and global order and what kind of order they might create from that position of leadership,” he writes. “In many places, but not all, it is a zero-sum game because it is over a positional good – that is, one’s role within a hierarchy.”

Doshi’s book, released on July 8, is not yet available in China. But Chinese analysts who have secured copies are sceptical of his interpretations of Chinese ambitions, and warn that the two powers need to engage in dialogue to dispel suspicion.

Zhu Feng, an international relations expert from Nanjing University, said his biggest problem with Doshi’s book was that it “overly uses the American perspective to exaggerate China’s strategy”.

“China is not trying to displace the United States, the current world order or the US hegemonic position,” he said. “Although many people in China domestically think that the US is in decline, most international relations observers and scholars and people in the Chinese government do not.

“The perspective in this book aggressively demonises China and, most importantly, the argument matters less than its efforts to justify a more hardline US policy on China.”

“[Biden’s] administration is similarly emphasising strategic competition between the two, this question of who will lead the world order, the fight between democratic norms and autocratic ones and the notion that China wants to displace the US,” Wei said.

“Biden wants to separate cooperation and competition with China, but from China’s perspective, if they are asking to cooperate but also engaging in suppression, they will not accept this.”

Wei said that while Doshi’s book contained extensive research on China’s domestic politics and its belt and road programme, the argument that China had been strategising to replace the US since the Cold War was “clearly an overstatement”.

“From Deng Xiaoping’s era, China was focused on reform and opening up, which was not about displacing the West but seeking to open up to and learn from the West to reform China,” he said.

“In the 1990s, after the trifecta of events Doshi talks about, Chinese leaders were very concerned about Western intentions towards China, and the attitude towards the US did change, not to try to displace the US but to adopt a defensive posture to dispel Western concerns about China.

“But [Doshi’s] view that China had been trying to displace the US since then, seeking to first blunt US power since it was not strong enough at the time, makes the historical mistake of trying to infer Chinese intentions at the time from the perspective of the current situation in China-US relations.”

In unprecedented move, China tells US what it must do to repair relations

China’s response to the US’ more explicit efforts for competition will be to push back.

“China’s solution is easy – if the US wants to decouple, then China will stand firm in not decoupling,” Zhu said. “If the US wants to de-sinicise, then China will stand firm against de-sinicisation. The core of it is that China will continue to walk steadily in its own path.”

“If I were in Beijing and I read Doshi’s book and I realised where Doshi is in the hierarchy in the foreign policy world, I might say OK, so that’s how they’re going to play it, it’s going to be containment,” he said. “We’re going to have to figure out a strategy to blunt the blunting, to get around the blunting.

“But I think Beijing already senses, after the last four years, that the United States has woken up to ‘the China threat’, and so I think that this is kind of baked into the cake already.”

Latham, who has already assigned the book as reading for his US foreign policy students, said his fear was that the US view on China would lead to a different type of cold war between the powers.

“The common sense in Washington these days is very much, we’ve got to stop [China], we’ve got to play hardball, from the Arctic to Africa to Taiwan to Venezuela, everywhere,” he said. “I think big powers are always going to butt heads and you have to figure out a way to make that work, short of going to war.”