Why China is breaking with tradition and setting a range for its annual growth target

Beijing is likely to set its annual growth target within a range for 2016, something it has done only once before, in 1995, reflecting the indecisiveness of policymakers over a question that will impact both China and the world: reform the economy or pursue growth?

Premier Li Keqiang (李克強) is expected to set a gross domestic product (GDP) growth target of 6.5 per cent to 7 per cent when lawmakers gather for this week’s National People’s Congress.

Usually, China prefaces its growth targets with the word “about”. It had a target of “about 7 per cent” in 2015 and “about 7.5 per cent” in 2014.

On Wednesday ratings agency Moody’s downgraded its outlook on the government bond rating from “stable” to “negative”.

READ MORE: Why are the world’s markets going crazy? It’s China’s economy, US monetary policy and commodity prices, says France’s finance minister

Setting a range offers more leeway for Li’s government to manoeuvre economic policies and make it easier for Beijing to declare victory in meeting targets. It also reflects a certain level of indecisiveness from leaders on how to handle conflicting goals – whether it should bravely honour its promises of structural reform, or give in to pressure to address slowing growth by easing monetary policy and boosting fiscal spending.

An unprecedented amount of bank credit in January, an unexpected cut in the central bank’s required reserve ratio announced on Monday, and dovish comments from central bank governor Zhou Xiaochuan (周小川) at the G20 meeting in Shanghai last week all suggest Beijing, at least for now, is putting its ambitious reform plan on the back burner to focus on arresting the slowdown.

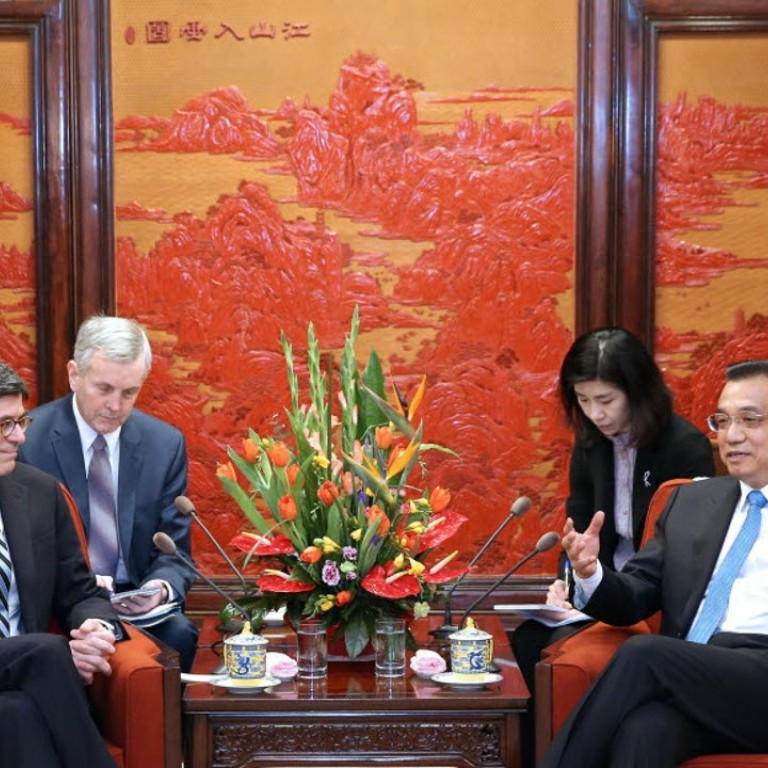

Li told the US Treasury Secretary Jacob Lew on Monday China would “forcefully push forward” structural reforms, especially on the “supply-side”, reiterating his view that stimulus is not right for China’s economic future.

“Policy messages have been really confusing in recent months,” said Li Weisen, an economics professor at Shanghai’s Fudan University, who attended symposiums with policymakers last week. “There are some voices advocating policy easing, and equally important voices saying ‘no policy easing please’.”

Christopher Balding, an associate professor at the HSBC Business School of Peking University in Shenzhen, said Beijing’s problem was it failed to see and accept “economics is about trade-offs”.

He said: “Yes, you can continue to expand credit rapidly, but that will have trade-off costs like higher financial risks and poor capital allocation towards the state sector. Yes, you can deleverage, but that is going to lower short term growth.”

The trade-off between economic rebalancing and growth will always be a challenge. While China’s economic officials were doing their best to support growth, they faced constraints, said Tim Condon, head of Asian research at ING in Singapore. “They want to phase out inefficient capacity, they don’t want to ruin the environment – those are drags on growth,” he said.

“The jury was out” on how far Beijing would pursue policy easing, and it was too early to conclude that it was returning to the playbook of 2009 when it pursued growth at the cost of forgetting structural reforms, Condon said.

READ MORE: Stand aside Likonomics ... here’s Xiconomics: How President Xi Jinping is taking the reins of China’s economy

Beijing has been willingness to take some pain. Labour Minister Yin Weimin (尹蔚民) said on Monday China was ready to make 1.8 million workers redundant at coal mines and steel mills. Total lay-offs caused by the clampdown on overcapacity and polluting sectors could be up to six million in the next two or three years.

Using a range as a target for growth could be misleading, said Zhu Baoliang, a researcher at the State Information Centre think tank. “If the headline growth is targeted in a range, should other indicators such as money supply and employment be targeted in a range as well?” ” Zhu said last month. “Or should all local governments follow suit to set their growth targets in ranges?”

Some provincial governors have already done so. Li Qiang, governor of eastern Zhejiang (浙江) province, set a provincial growth range of 7-7.5 per cent and Guo Shuqing, Shandong (山東) province’s governor, targeted growth of 7.5-8 per cent for 2016.

“A range target from the central government can actually reduce growth pressure on local governments – if the growth target is 7 per cent, basically every province is trying to achieve growth higher than that,” said Frank Tang, an economist at research firm North Square Blue Oak.

“Now the message has changed – it’s OK as long as growth is not below 6.5 per cent.”

Wen Bin, chief economist at China Minsheng Banking Corp in Beijing, said the key message in the range was its lower end of 6.5 per cent. China had “made it clear there’s a bottom” as it needed a minimum growth rate to achieve its strategic goal of doubling the economy by 2020 – the year before the 100th anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party, Wen said.

READ MORE: Can Xi Jinping turn China’s political theatre into a hit one-man show?

Premier Li’s has used different ways to recharge the economy, from urbanisation pushes to backing internet entrepreneurship, but his disdain for massive stimulus has been consistent over the past three years. In December, Li wrote in The Economist that “my government has resisted the temptations of quantitative easing and competitive currency devaluation. Instead, we choose structural reform.”

By setting a target range, China would not be shy to flex its monetary and fiscal muscle to avoid an economic hard-landing if it saw a risk of growth sliding below 6.5 per cent, Ding Shuang, chief China economist at Standard Chartered in Hong Kong said. “The upper limit of 7 per cent also shows Beijing is reluctant to adopt an all-out stimulus – it’s unnecessary to push growth [above] 7 per cent.”

While the annual GDP target is politically important and seen as an sign of Beijing’s policy intentions, using it to predict actual growth has its limitations. In 1995, then premier Li Peng (李鵬) set a GDP growth range of 8-9 per cent – China’s actual GDP growth that year was 11 per cent.