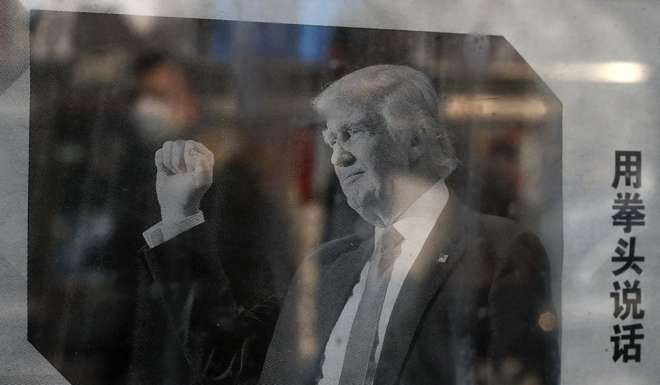

Just how badly could Trump’s threatened 45pc tariff hurt China?

Economists say it could lead to a halving of US imports, or worse

US president-elect Donald Trump’s threat to impose a 45 per cent tariff on imports from China is no longer being dismissed as mere election rhetoric following his nomination of two prominent China critics as key members of his trade team and the discovery of a long-forgotten presidential power to raise tariffs.

Trump has named Peter Navarro, the author of Death by China, as director of his White House’s newly created National Trade Council and fellow China critic Robert Lighthizer as US trade representative.

Meanwhile, former deputy US trade representative John Veroneau, now a lawyer specialising in international trade at the Washington-based law firm Covington & Burling, discovered US presidents have more power to unilaterally raise tariffs than previously thought.

Even though Trump has vowed to pursue a more aggressive trade policy with China, it was previously believed that United States law only allowed a president to unilaterally impose tariffs of up to 15 per cent for as long as 150 days. However, Veroneau and colleague Catherine Gibson wrote in an article on the Law360 legal news website last month that a section of the Tariff Act of 1930 last referred to in 1949 – ironically in relation to China – remained in the statute books and could allow a president to impose tariffs of up to 50 per cent and then, if escalation was required, block imports completely.

That raises the stakes enormously, with some economists predicting a halving or worse of Chinese exports to the US – worth US$385.2 billion in 2016 according to the General Administration of Customs – if a 45 per cent tariff is introduced.

More importantly, the direct export losses from the imposition of such tariffs would represent only a small part of Beijing’s troubles in a trade war against the US, with the global trade system that has boosted China’s prosperity and economic might over the past two decades unlikely to survive the conflict.

Kevin Lai, research head for Asia excluding Japan with Daiwa Capital Markets, wrote in a research note that punitive tariffs of 45 per cent would lead to an 87 per cent fall in China’s exports to the US, while HSBC economists led by Qu Hongbin predicted they would result in a halving of Chinese shipments to the US.

The US is China’s biggest export market, accounting for 18 per cent of total exports, and China’s overall exports would be expected to shrink at least 9 per cent if Trump carried through with his tariff threat. There would also be significant suffering due to the collapse of businesses and job losses, with Lai estimating that China’s gross domestic product could be trimmed by 4.8 per cent.

Shen Jianguang, chief Asia economist at Mizuho Securities, estimated that China’s exports had created 120 million jobs, including 20 million making products for the US market.

More broadly, a full-blown trade war between Beijing and Washington could encourage other countries to become hostile to Chinese products, thus wrecking China’s powerful export machine, warned Professor Yu Miaojie, from Peking University’s National School of Development.

“What is more worrying is that other countries may follow suit,” he said. “As a result, Chinese exporters may not only lose the US market but also the wider market in advanced countries.”

In fact, the European Union, China’s second-biggest export market, is also getting increasingly frustrated with a flood of cheap Chinese products and curbs on access to the Chinese market.

Meanwhile, mistrust between Beijing and Tokyo is clouding bilateral trade, and China has raised the prospect trade sanctions on South Korea, such as limiting imports from that country, to express its unhappiness over Seoul’s plan to allow a US anti-missile system to be based on its soil.

Trump’s threat could significantly undermine China’s position as a trade superpower.

China emerged from an economic backwater in the 1980s to become a poster child for economic growth in early 2000s thanks to the country’s integration into the global value chain. The country’s cheap labour and low-cost inputs, combined with technology and facilities from advanced economies, made it the world’s factory.

But the wind is changing. China’s overall exports have started to lose momentum in recent years as overseas demand slowed and domestic costs increased, and many manufacturers have left China or are planning to move out.

Fraser Howie, director of Newedge Financial in Singapore and a co-author of Red Capitalism: The Fragile Financial Foundation of China’s Extraordinary Rise, said Trump had the ability to “completely screw a lot of the global trade mechanics” and Beijing found itself being “forced into making on-the-spot decisions in response to events”.

The Chinese government has not responded directly to Trump’s trade threats, although Beijing is quietly considering possible retaliatory measures against the US if a trade war breaks out, including targeting well-known US companies with tax or antitrust probes, according to a Bloomberg report.

On the surface, the Chinese government is trumpeting the virtues of free trade. Finance Vice-Minister Zhu Guangyao said last month there would be no winner in a trade war between China and the US, and the damage would spill over to the rest of the world.

However, after Trump nominated Lighthizer as his US trade representative, the Beijing-based Global Times, a tabloid published by the People’s Daily group, carried an editorial that warned there were “big sticks” waiting for Trump behind the doors of China’s Ministry of Commerce.

To be fair, bilateral trade between world’s No 1 and No 2 economies has always been a quarrelsome affair, with clashes over everything from poultry to hi-tech products. According to calculations by Capital Economics, a London-based consultancy, the US currently applies anti-dumping penalties to 102 Chinese products and China does the same to 34 US products.

Some observers said they still expected Trump’s threat to impose a 45 per cent tariff on all Chinese products would turn out to be a bluff, designed to increase his leverage in negotiations.

Henry Chan Hing Lee, an adjunct research fellow at the National University of Singapore, said he expected Trump would continue to test China’s bottom line and the game of “pushing things to the brink” would only stop when domestic opposition rose in the US.

Jin Baisong, a researcher with a Ministry of Commerce think tank, said China might offer to buy more US products to help Trump’s plan of boosting US exports and creating more US jobs.

“China is willing to buy more,” Jin said. “Why not sit down to have a talk?”