From made in China to made for China … a soap maker’s journey to the West

Peter Pan used to target US market from China but he’s now setting up a factory in California and looking to tap into middle class spending on mainland

Chinese-American businessman Peter Pan Chengjian used to sell soaps and shampoos made in China to US consumers but is now preparing to do the reverse.

Pan, 60, opened a small factory in Shanghai in 1997 and exported personal-care products based on his own formulas for 17 years. But rising costs on the mainland led him to sell the factory in 2015 and he’s now preparing to open a new one near Los Angeles, California, that will ship US-made shampoos and lotions to China.

His experiences are a reflection of the profound changes seen in the American and Chinese economy in recent years, with China transforming itself from a factory base to a consumer market and the United States, which saw its manufacturing sector hollowed out for decades, beginning to see the repatriation of production, which is a priority for new US President Donald Trump.

Pan was born in Xian, Shaanxi province, and was dispatched by a state-owned company to Los Angeles in the 1980s. He applied for US citizenship in the early 1990s and founded his own brand, Panrosa, in the US.

When he returned to China as a “US merchant” in the late 1990s, he found a country desperate to integrate into world markets and red carpets rolled out for him.

Despite a small blip during the Asian Financial Crisis in late 1997, the year he established his factory in Shanghai, China’s exports took off. The Chinese government kept the yuan’s exchange rate against the US dollar unchanged at around 8.3 from 1994 to 2005, making Chinese products competitive in US supermarkets. Chinese labour was cheap, and the Chinese authorities treated foreign investors as VIPs.

“It was really a good time,” Pan said at the Canton trade fair in Guangzhou last month. He’d attended the trade fair before but it was the first time he was there as an importer.

According to World Bank figures, China’s export growth rate in 2003, two years after it joined the World Trade Organisation, was just over 20 per cent, five times higher than the world average.

The honeymoon gradually came to an end, and it was obvious by 2008 that the days of cheap Chinese exports were over. Labour costs started to rise steeply as the supply of surplus labour from rural areas dried up, cheap land and favourable tax treatments were no longer offered by government, and the financial crisis put a damper on demand for Chinese products in US and European markets.

Factories such as Pan’s were no longer a priority for Shanghai, China’s most-developed city, and he followed many other manufacturers further inland, where costs were a bit lower, buying land for a factory in neighbouring Jiangsu province in 2011. But his situation kept worsening. The yuan, which had been appreciating against the US dollar since 2005, was approaching a peak of about six yuan to the dollar in 2013, and regulatory and labour costs kept growing rapidly.

Pan realised there was little room for profit in keeping his Chinese factory and he sold it to Reward Group, a Beijing-based detergent and food conglomerate, in 2015. Reward is investing US$40 million in Pan’s new factory in the US, which will cost around US$50 million in total.

The next year, he bought a factory sitting on four hectares of land in the city of Corona, about 72km southeast of Los Angeles. The city, once dominated by citrus orchards, ranches and dairy farms, is gradually becoming a manufacturing base. Other firms with factories in the city include guitar maker Fender and beverage producer Monster Energy.

Pan’s factory will rely heavily on automation and only have about 50 workers – half the number employed at his former factory in Jiangsu. It will start production late this year, with a third of its output destined for China.

“If you include everything, the manufacturing costs in the US are lower than China,” Pan said.

Boston Consulting Group said in a recent report that China had been losing its appeal as the world’s largest workshop because labour was no longer cheap and electricity and natural gas costs were higher than in the US.

“Despite the recent weakening of the yuan, and factoring in the differences in productivity and energy costs, China’s manufacturing cost advantage over the US shrank from 14 per cent in 2004 to an insignificant 1 per cent in 2016,” Harold Sirkin, the group’s lead expert on global manufacturing cost competitiveness, wrote.

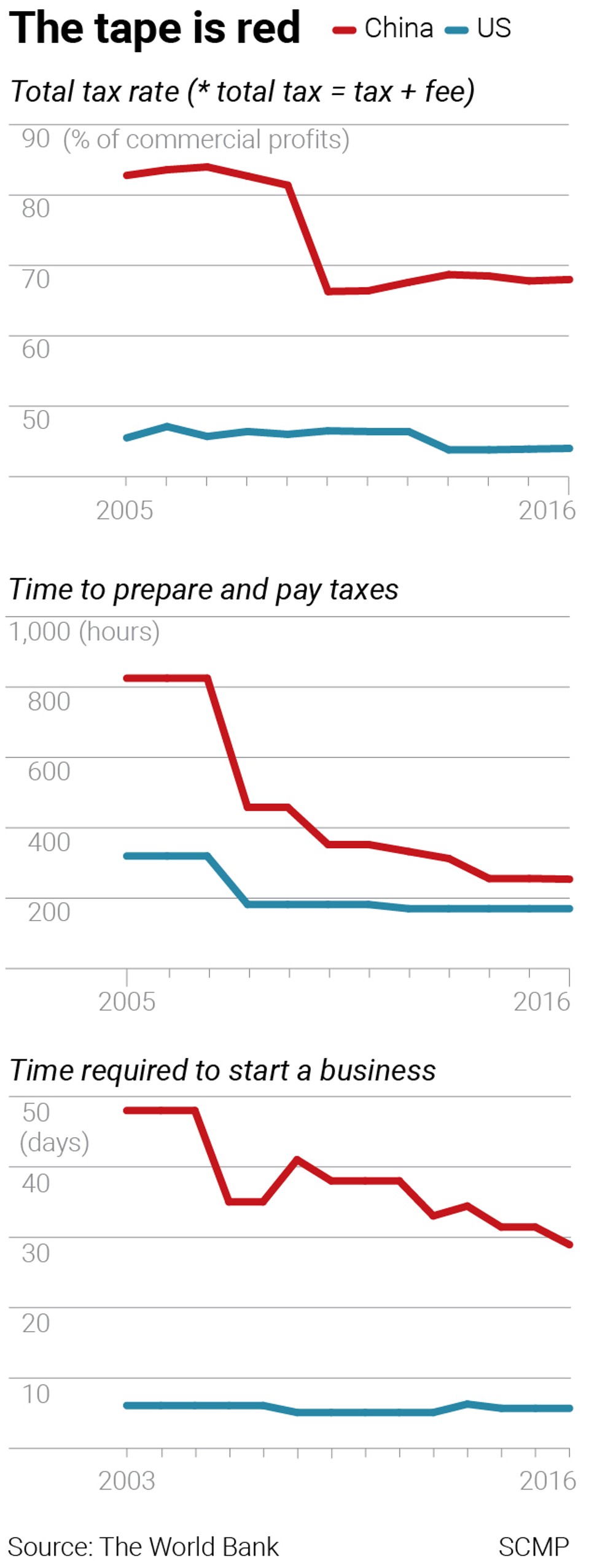

And then there’s the tax burden. When vehicle glass king Cao Dewang, the chairman of Fuyao Glass, decided last year to invest US$1 billion in a US factory, it triggered a debate on whether China’s heavy tax burden was hollowing out its manufacturing sector. According to the World Bank, Chinese companies paid about 68 per cent of their profits in taxes and fees last year, compared with 44 per cent in the US.

The tax burden in China looks even heavier in the light of Trump’s pledge to cut corporate taxes in the US. In China, Premier Li Keqiang has repeatedly called for tax cuts and the scrapping of fees, but local tax departments still have large discretionary power to interpret and collect them. A report from the Institute of Industrial Economy at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, a government think-tank, found that a Chinese business that lost eight million yuan one year was still forced to pay 400,000 yuan in taxes by local tax assessors.

“Cao’s company is bigger than ours, but I ran a business too,” Pan said. “I know everything from A to Z, and am familiar with all the details. He is talking about his industry. But it’s the same in my industry.”

Pan said it was also much simpler to open a factory in the US than in China, where he’d had to deal with numerous government agencies.

Beverage tycoon Zong Qinghou, the chairman of Hangzhou Wahaha Group, complained publicly late last year that his business was subject to more than 500 types of government taxes and charges. The National Development and Reform Commission replied in January that the total was actually 317.

Like many Chinese-American businessmen, Pan voted for Trump in last year’s US presidential election, in large part because of his pledge to cut corporate taxes in the US from 35 per cent to 15 per cent.

“I don’t look at him as a politician,” Pan said. “I look at him as a businessman.”

China is California’s third-largest export market, with US$14.4 billion worth of goods shipped across the Pacific last year. Its top exports to China included computers, transport equipment and chemicals.

Jeffery Williamson, an adjunct professor of global marketing at California State University Fullerton, said the state’s entertainment industry had also made it fertile ground for the manufacture of health and beauty products. He estimated that up to a fifth of the roughly US$1 billion of such products exported from the US to China every year were made in California.

Williamson said it made more sense to make something consumers put on their skin in the US because it put few barriers in the way of individuals developing their own formulas but also had extremely strict manufacturing rules to ensure quality.

“I think a brand made in the US makes up for the cost difference,” he said. “It’s an implied endorsement ... made-in-US makes customers more comfortable they are buying something safe.”

In China, the personal and household chemicals sector is now very competitive. Joint ventures and foreign giants such as Unilever and L’Oréal control around 70 per cent of the market. Pan is looking to branch out from shampoos and detergents into high-end areas, such as women’s skincare products, to tap into the purchasing power of China’s growing middle class. He’s outsourced production while the new factory is being completed and has opened three sales offices, in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou.

While it was cheaper in theory to produce goods close to where they were consumed, Pan said America’s US$347 billion trade deficit with China last year meant there was plenty of room for China to import more, and the Trump administration was pushing Beijing to open up more of its market to US producers. It was also about 50 per cent cheaper to ship goods to China by sea than to export goods by sea from China, he said, because many containers heading back to China were empty, which depressed prices.

For Chinese distributors, imported lotions and sanitisers offer fat margins. A 500ml bottle of Panrosa shampoo which wholesaled for US$2.50 could end up selling for 80 yuan (US$11.74).

But China’s customs agency strictly scrutinised imports of such products, Pan said, which meant “we need to earmark more resources on public relations on the ground”.

Williamson said the global system could no longer rely on US consumers to be the “freight train”.

“We used to call that the freight train – the US consumers – that pulled the world economy out of recession,” he said. “Today it’s more the Asian consumers that are going to do that because there is more growth over there for consumption.”