Exclusive | Off the charts: why Chinese publishers don’t want maps in their books

Publishing sources say they are leaving maps out of books entirely to avoid going through the long and complicated review process

New rules have made it so difficult for publishers to get maps of China past the censors that some are choosing to leave them out of books entirely to avoid the tortuous review process, according to three separate publishing sources.

Publishers are less willing to produce books with any type of map of China, and some even suggest their authors remove maps before they will go ahead with a book deal because they consider the process of getting them approved for publication to be difficult and costly, the sources told the South China Morning Post.

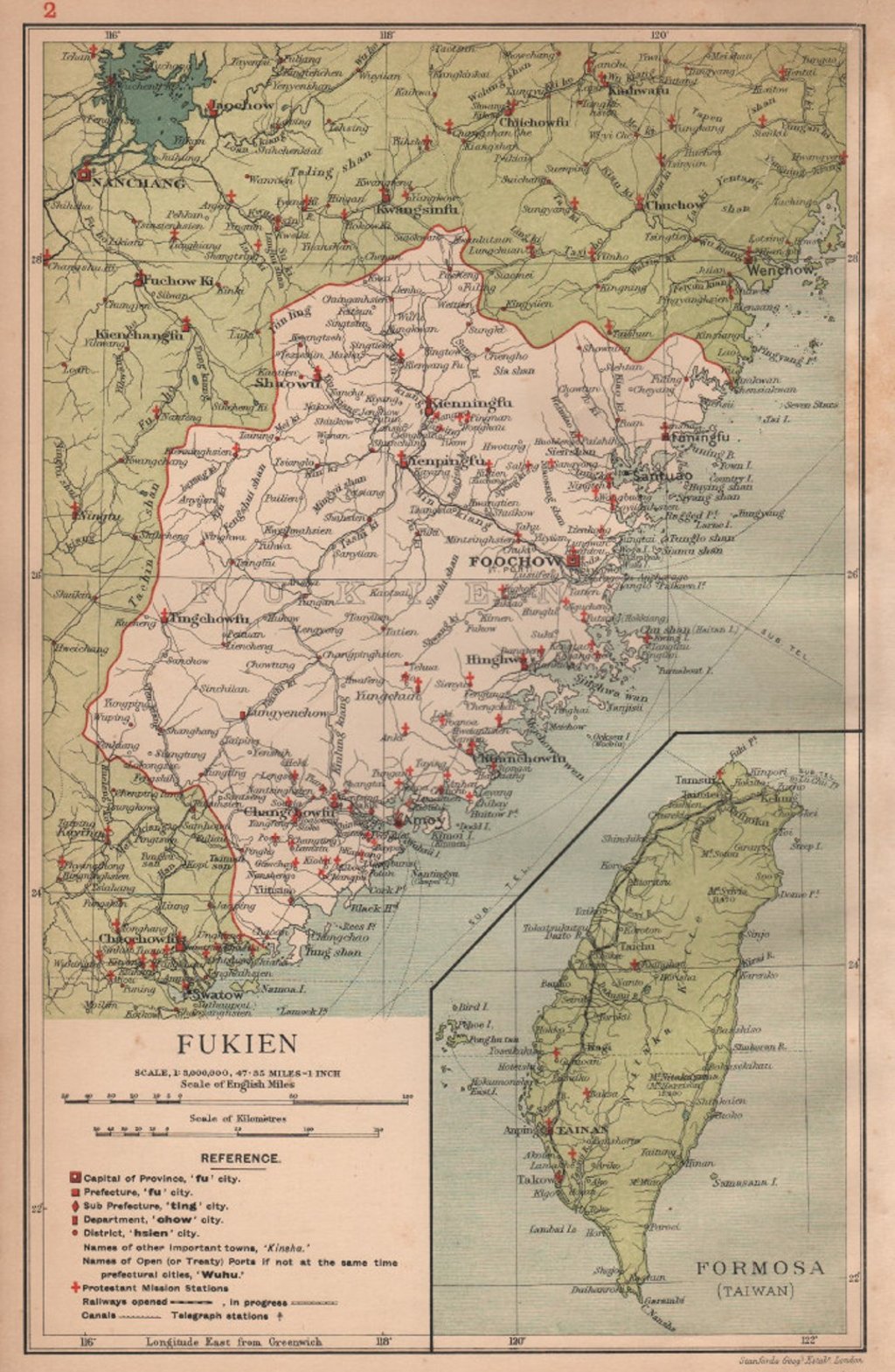

While Beijing has always been fastidious about maps of China – particularly whether they include the nine-dash line showing its disputed claim in the South China Sea, and the self-ruled island of Taiwan – the censors are now also turning their attention to how the country is represented on maps of the world, and even historical maps.

Under new rules that took effect in January, all maps of China, regional maps of Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, world and historical maps must be approved by the State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping before they can be published, republished, exported or imported. Only maps of tourism sites, public transport and local neighbourhoods are exempted.

The process to submit maps for approval is long and complicated. For most publishers, it could take more than a year, or even longer, to get a map approved – although the bureau states it will take up to 20 days to review applications “upon receipt of the required documents”.