The making of a space junk disaster? China’s low-cost microsatellites may lead to ‘space pollution’, say experts

There are now nearly 1,400 satellites orbiting the earth and the number could more than double in next five years

Chang Guang Satellite Technology, a private space start-up in Changchun, Jilin province, released a series of high-definition satellite images last month that zoomed in on foreign military facilities such as Japan’s naval headquarters, US aircraft carriers, Edwards Air Force Base in California and Area 51 weapons testing grounds in Nevada.

It was the first time such images had been released in China and they went viral on mainland social media.

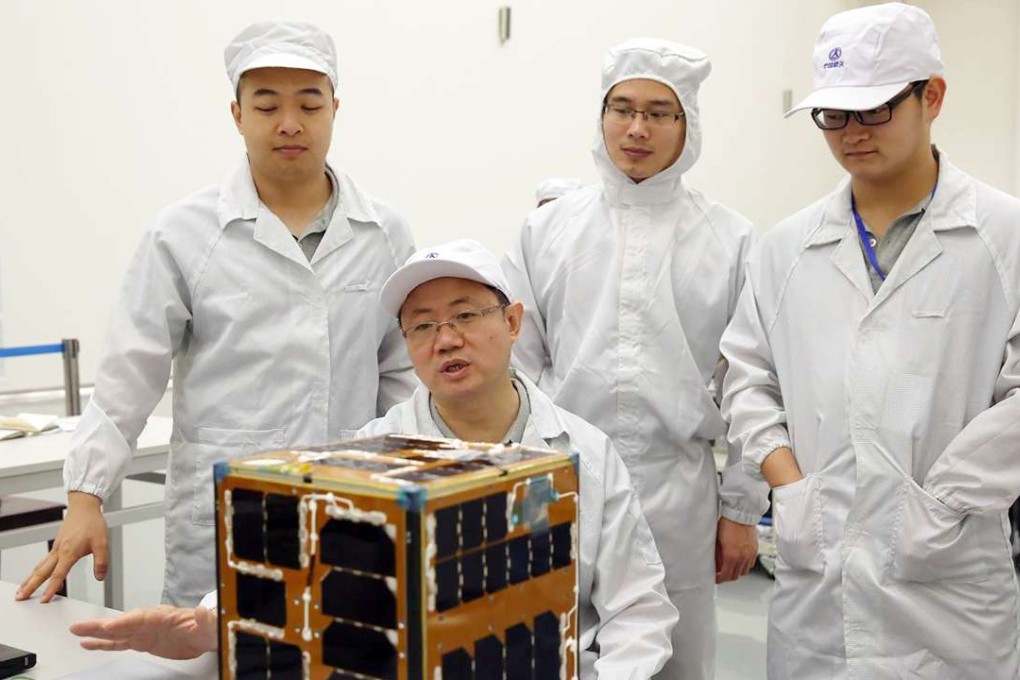

The images were taken by JLCG-1, a microsatellite constellation launched last year consisting of four satellites, the smallest of which weighs just 65kg, able to take photographs at resolutions of up to 0.72 metres per pixel.

The JLCG constellation orbits 650km above the earth, slightly above the International Space Station. But the satellites have limited orbital manoeuvrability, meaning that if they enter into a collision course with the space station or other spacecraft in the busy lower-earth orbit, their operator would be unable to move them out of the way.

The number of satellites orbiting the earth has jumped 40 per cent to nearly 1,400 since 2011, and in five years the number could more than double, according to some space industry estimates. The increase has mainly been driven by technological innovations with have reduced the size of satellites, in some cases down to something the size of a smartphone.

In June, US aviation giant Boeing filed an application to the US Federal Communications Commission to launch nearly 3,000 satellites to provide broadband internet services, which prompted traffic jam concerns in the US as no single federal government agency had the means or authority to track a microsatellite and order it to move out of the way to avoid a collision.