Deadly drug used by Russian forces in 2002 hostage crisis available for worldwide sale online

Chinese vendors offering international shipping for carfentanil, often used as chemical weapon or elephant tranquiliser

It’s one of the strongest opioids in circulation, so deadly an amount smaller than a poppy seed can kill a person. Until July, when drug users in the United States started overdosing on carfentanil, the substance was best known for knocking out moose and elephants – or as a chemical weapon.

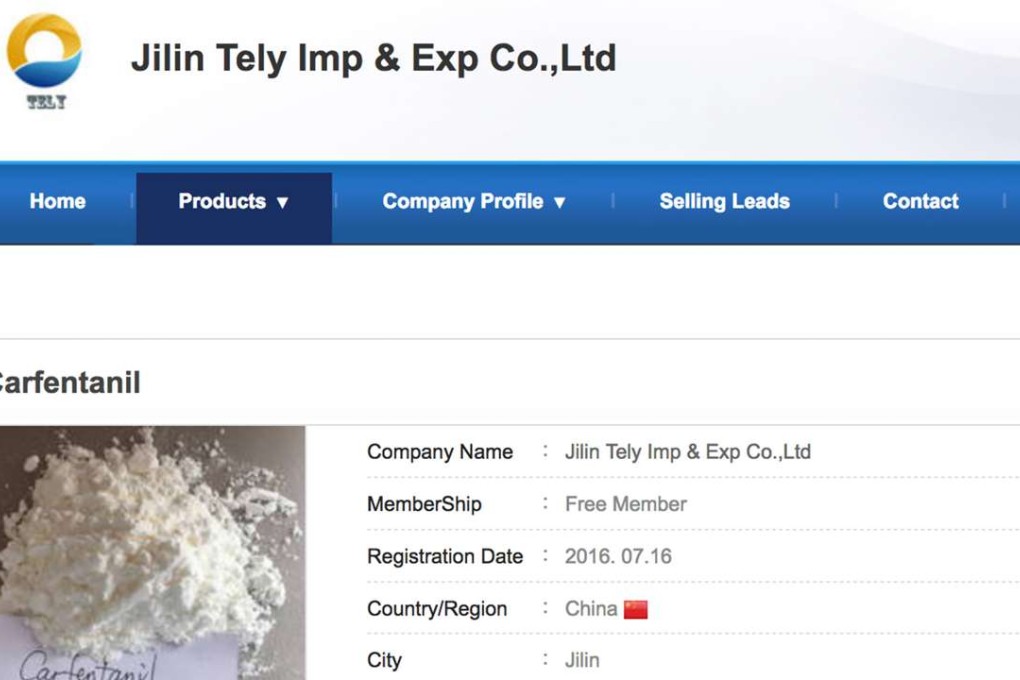

Despite the dangers, Chinese vendors offer to sell carfentanil openly online, for worldwide export, no questions asked, an investigation has found. The investigation identified 12 Chinese businesses that said they would export carfentanil to the United States, Canada, Britain, France, Germany, Belgium and Australia for as little as US$2,750 a kilogram.

Carfentanil burst into view this summer as the latest scourge in an epidemic of opioid abuse that has killed tens of thousands in the US alone. In China, the top global source of synthetic drugs, carfentanil is not a controlled substance. The US government is pressing China to blacklist it, but Beijing has yet to act.

“We can supply carfentanil . for sure,” a saleswoman from Jilin Tely Import and Export Co. wrote in broken English in a September email. “And it’s one of our hot sales product.”

The investigation did not include ordering drugs and the products offered were not tested to find out if they were genuine.

China’s Ministry of Public Security declined multiple requests for comment.