The big questions about missing tycoon: why and why now?

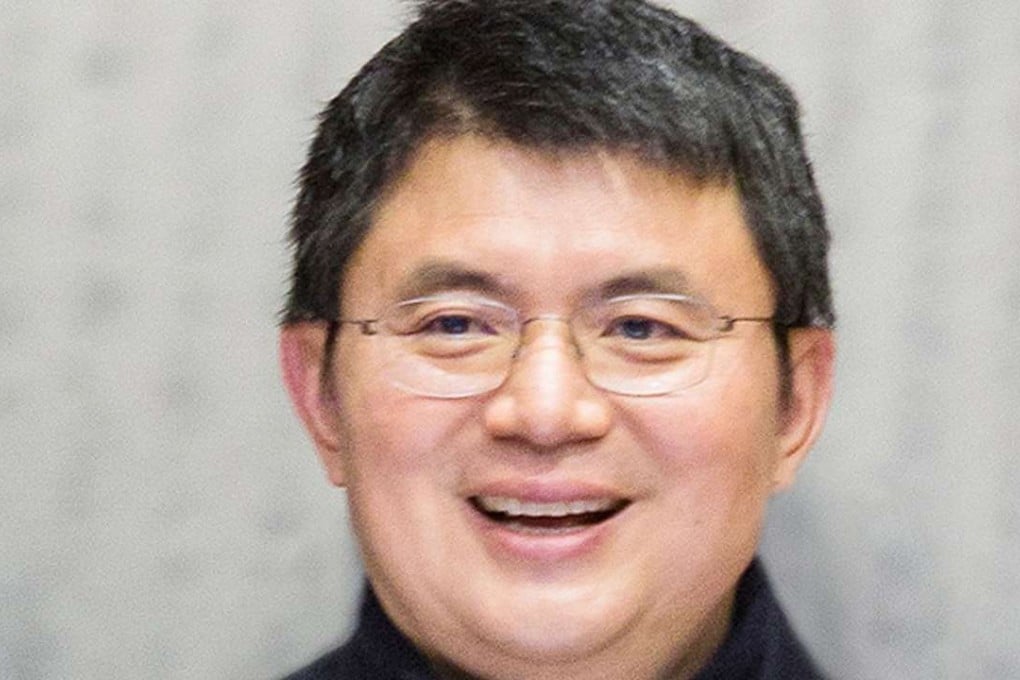

Mainland billionaire Xiao Jianhua has been linked to investigations into top-level bribery and market manipulation

Hong Kong’s bustling Central district was quiet in the small hours of January 27, the last day of the Year of the Monkey, when two seven-seater vans quietly pulled up outside the luxury Four Seasons Place serviced apartments. The eve of the Lunar New Year is always a big occasion for family gatherings and the crowds on the streets were thinner than usual.

Five men left the vans at about 1am and went straight into the lift lobby. Moments later, they reappeared on the 28th floor and knocked on the door of mainland billionaire Xiao Jianhua, who was staying in one of the several apartments he had rented there for two years – each costing more than HK$200,000 (US$25,000) a month.

Two hours later, Xiao emerged with two female bodyguards and the five men. They got into the two vans and left the hotel precincts without making a scene. Almost 12 hours later, Xiao and his entourage reappeared at the Lok Ma Chau border crossing between Hong Kong and Shenzhen. They passed through border controls with valid documents and disappeared into the mainland Chinese city at 3pm.

In the weeks since, Xiao has been linked to mainland investigations into top-level bribery and market manipulation and been caught up in the central government’s anxieties about financial and political risks.