Why Xi Jinping put his new city dream in old hands

Former Shanghai mayor Xu Kuangdi, 79, played key role in Pudong’s development

President Xi Jinping has put his dream for the Xiongan New Area in old hands.

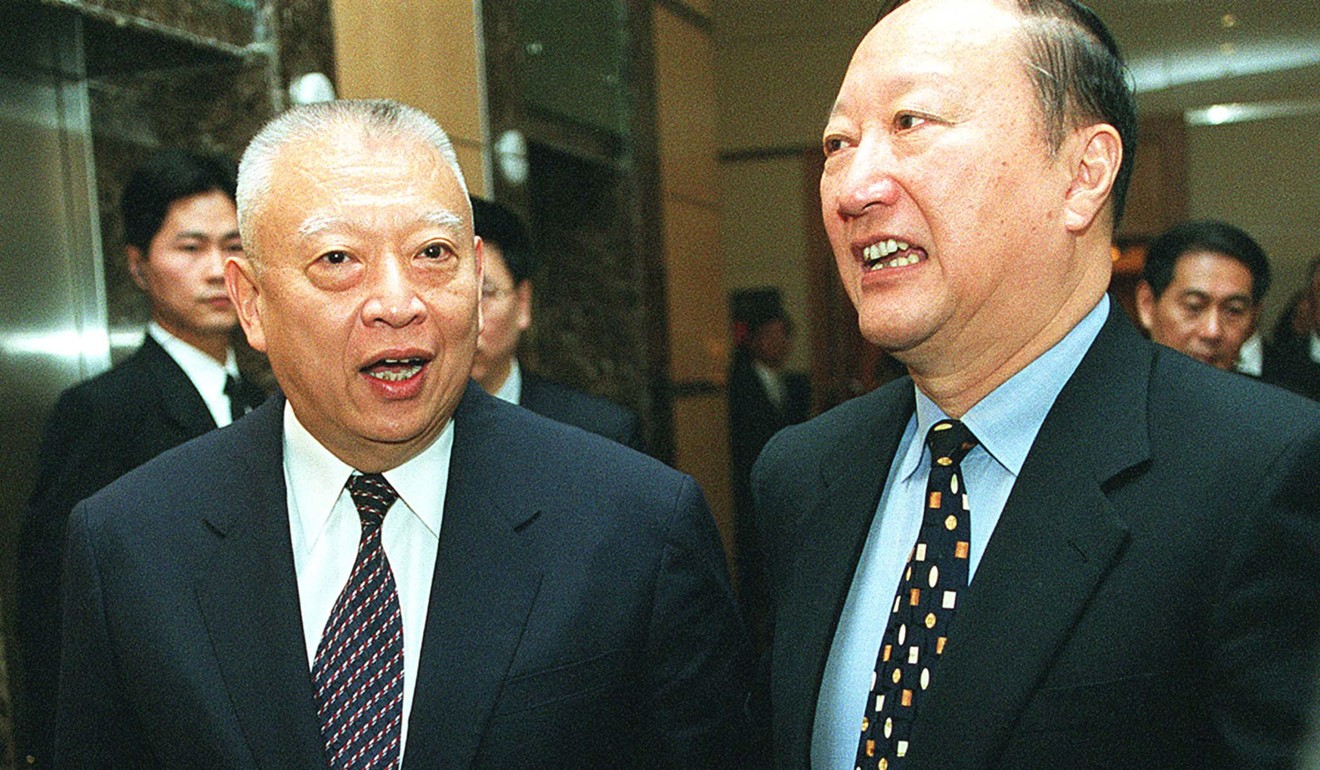

During a site inspection in February, septuagenarian former Shanghai mayor Xu Kuangdi, the man who played a key role in transforming that city’s riverside Pudong backwater into China’s financial hub, was photographed at Xi’s right hand.

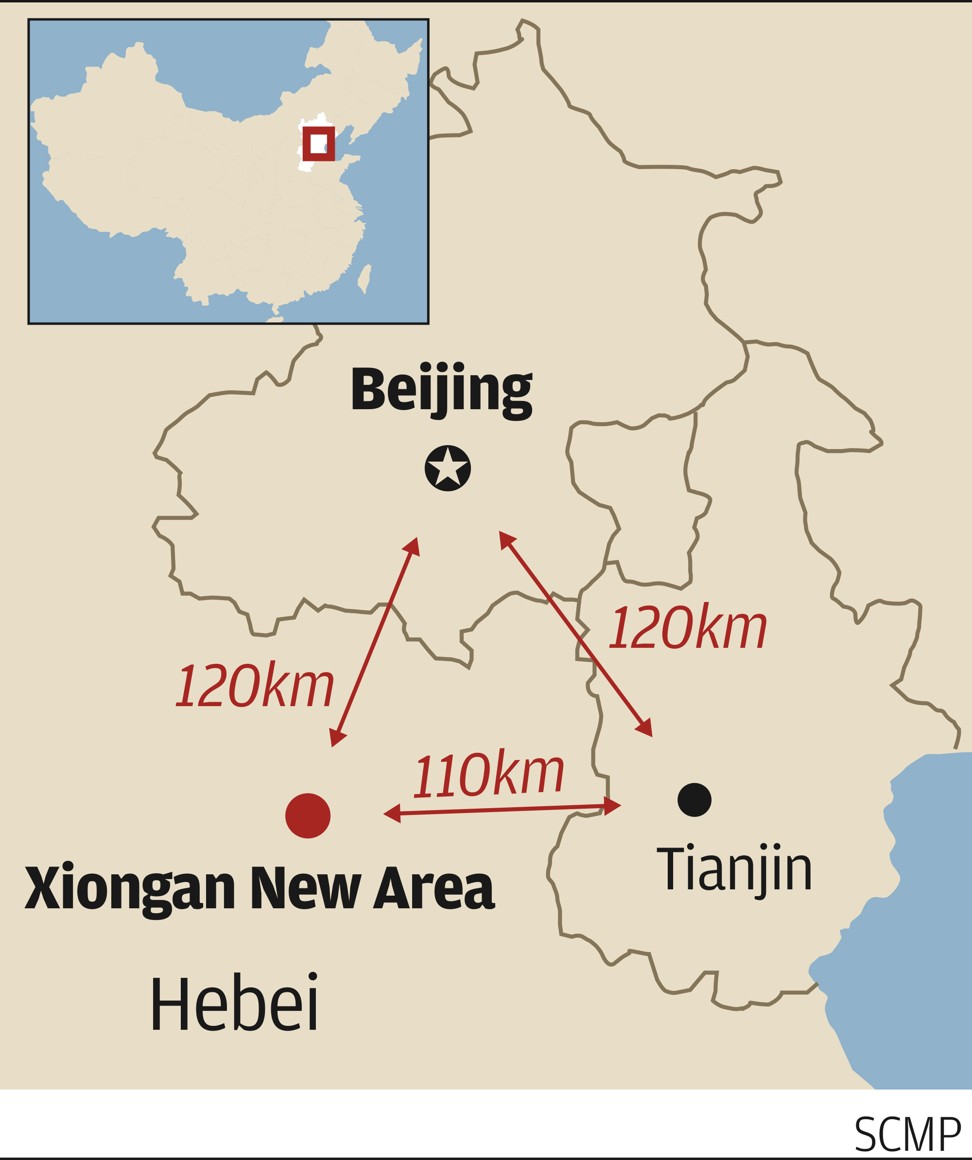

Xu, now 79, was mayor of Shanghai from 1995 to 2001. His new role in Xi’s “thousand-year” plan to develop the city of Xiongan, encompassing three counties in central Hebei, is a reflection of the president’s preference for a voice free from the vested interests of ministries and local authorities.

After state media announced on April 1 that China planned to build a new city in Hebei to rival Shenzhen and Pudong, Xu told the official Xinhua news agency Xiongan was chosen because the area was like “a piece of white paper”, making it possible for Xi to create a dream city.

Xu retired from all public positions in the past decade, standing down as a vice-chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) in 2013 and as president of the Chinese Academy of Engineering in 2010. However, he assumed a low-profile advisory role in 2014 as the head of the expert committee on the president’s Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei integration plan.

His Xiongan role adds a solid endnote to a long career that has tracked China’s transformation from a weak country into a global economic powerhouse.

“Xu is a wise and upright person who is always passionate about the future,” said Zhou Hanmin, a vice-chairman of Shanghai’s municipal CPPCC who worked with Xu during his time as the city’s mayor.

Shanghai residents still praise Xu for his non-bureaucratic style, economic savvy and fluent English.

Born in 1937, the year the Marco Polo Bridge incident sparked a war between China and Japan, Xu was given the name Kangdi, which means “fighting against the enemy”. In 1944, when he was a refugee studying at a primary school on the Burmese border, his teacher told him the war would come to an end and he should change his name Kuangdi, which means “upholding justice and peace.”

Xu enrolled at the Beijing Steel Industry College in 1954 and after graduating in 1959 spent another four years there working as a teaching assistant before moving to Shanghai to teach at the Shanghai Engineering College.

He was sent to a labour camp in rural Anhui for a year in 1971 but, other than that, spent his entire early career researching and teaching about steel production.

In his forties when late paramount leader Deng Xiaoping opened up the country to the outside world, starting to embrace the international market after three decades of Soviet-style state planning, Xu worked as a visiting scholar at Imperial College in London in 1982 and 1983.

Although Xu had lived and worked in Shanghai, China’s biggest city, for years, he later said he had been shocked by the sight of London supermarket packed with different products because China was impoverished at the time and many items were in short supply.

“I took a picture because I was stunned,” Xu told Phoenix Television in a 2008 interview. “How could a supermarket have so many things?”

In 1984, Xu was invited to work as an engineer at a Swedish steel company, where he learned about project bidding, cost calculation, bank loan applications and production management. He returned to China a year later and was promoted to vice-president of his Shanghai college. In 1989, he joined the Shanghai municipal government as head of the city’s higher education bureau.

A trip to Europe in 1990 as a minor member of a delegation led by Shanghai party secretary Zhu Rongji, who went on to become premier eight years later, changed Xu’s career path.

When they visited the Paris Bourse, the 160-year-old home of the French capital’s stock exchange, the official translator had no idea what “index futures” were. Xu intervened and explained the economic term to Zhu, who was deeply impressed, according to media reports.

The Shanghai Observer reported that Zhu asked Xu on the return flight to Shanghai whether he would head the city’s economic planning commission. Xu replied that he did not like the concept of a planned economy.

Zhu laughed and said: “I’ve finally found someone with a dislike of a planned economy to be director of the planning commission.”

So Xu stepped onto the political stage at the age of 54. He proved a capable official and the local economy took off in the early 1990s.

“When Xu was the mayor, Pudong saw a huge change ... his contribution to Pudong’s development was tremendous,” said Gu Jianguang, director of the Public Policy Research Institute at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Gu said Xu was hands-on in the development of Pudong. In one instance, when approving plans for Pudong International Airport in the 1990s, Xu decided on an airport capacity far beyond what Shanghai needed at the time. Gu said he was told many people at a meeting had questioned whether the airport was too large, but Xu replied: “Shanghai is like a baby and will grow bigger. His clothes should be made a size bigger to fit in the future, otherwise the clothes will need to be changed again and again.”

Xu also worked hard to solve “real problems” for Shanghai people. During his mayorship, the per capita living space of Shanghai residents increased by almost half, the foul-smelling Suzhou Creek winding through the downtown area was cleaned up and city’s transport infrastructure was improved, with new bridges built across the Huangpu River.

Xu’s abrupt resignation from the mayoralty at the end of 2001 fanned speculation he had been pushed aside by Shanghai party secretary Huang Ju, a political foe. Huang, who died in 2007, was a protégé of then president Jiang Zemin.

The official explanation for Xu’s resignation was that, at 64, he was too old to continue in the role of mayor.

Zhou said Xu had continued to work tirelessly for Shanghai in his final days as its mayor.

A month before Xu’s resignation, he flew to Paris to attend an International Exhibitions Bureau conference, where he delivered a speech in English as part of Shanghai’s bid to host the 2010 World Expo.

“Before the speech, he had rehearsals and asked us to point out any errors [in the speech draft],” Zhou said. Xu’s presentation won Shanghai the right to host the expo. It was in Paris that Xu received a call from Shanghai telling him he would have to step down when he returned home, the South China Morning Post reported in 2001.

Once viewed as a rising political star and a potential vice-premier, Xu was sidelined, being appointed party chief of the China Academy of Engineering.

It is not known why Xi picked Xu to become his chief adviser on Xiongan. But when he was briefly Shanghai party secretary before his promotion to Beijing, it’s likely Xi read Xu’s far-sighted vision for Shanghai, drafted in the late 1990s, which called for making the city an international economic, finance, shipping and trade hub by 2020.

Xi envisions Xiongan as a city free from problems like traffic congestion and pollution that plague other Chinese cities. Xu, personifying the old Chinese saying that “an old horse in the stable still aspires to gallop a thousand miles”, was the old, proven hand he chose to articulate that grand ambition into a workable plan.

“Xu is the ideal person to orchestrate the Xiongan project because of his experience, capabilities and extensive connections,” Gu said. “In addition, he is in good health.”