Isolated, tortured and mentally scarred ... the plight of China’s persecuted human rights lawyers

Many of those arrested are still being subjected to abuse and torture, campaigners say on second anniversary of 2015 purge

Exactly two years ago, in the dead of night, the quiet of Wang Yu’s Beijing home was shattered by the roar of an electric drill boring into her door.

Moments earlier, the internet connection to the apartment had been cut and the lights had gone out, plunging the prominent human rights lawyer – who was home alone after dropping off her husband and son at the airport earlier in the day – into an unsettling darkness.

The drilling stopped. A gang of men burst into the flat, shoved Wang onto the bed and handcuffed her. She was hauled out to a waiting vehicle, had a hood pulled over her head, and was driven to a secret facility whose location is unknown to this day.

There, the 45-year-old was forced to sit cross-legged for weeks inside a circle drawn on her bed. Any time she complained she was scolded or beaten.

A leading figure in China’s burgeoning human rights movement, Wang last month recounted the events of the night she was taken, and her subsequent detention and torture, to her defence lawyer Wen Donghai. It was their first meeting since she’d been released on bail last August following a televised “confession”.

Wang’s detention on July 9, 2015 marked the start of a national roundup – later to become known as the“709 crackdown” – of about 300 rights lawyers, legal assistants and activists from across China. Most were interrogated and released, but about 40 were taken into custody.

Two years on, the majority of the cases have been closed. Two people remain in prison – rights lawyer Zhou Shifeng is serving seven years and activist Hu Shigen seven-and-a-half years for subverting state power – while others were given suspended sentences.

Three more lawyers – Wang Quanzhang, Jiang Tianyong and Wu Gan – and possibly others are in custody after being formally arrested, but not sentenced, while about a dozen, including Wang Yu, have been released on bail though remain under strict surveillance.

Wang, who was also charged with subverting state power, has been under effective house arrest in her hometown in Inner Mongolia since her release. Surveillance equipment installed inside and outside the property monitors everything she says and does.

According to her lawyer, Wen, she is not permitted to contact the outside world or return to her home in Beijing. Wherever she goes she is followed by two security agents.

“Her memory has deteriorated severely, and she wants to see a psychologist, as she frequently suffers from fear and anxiety,” he said.

Wang told Wen that she was forced to take pills while in detention, but has no idea if they are to blame for the problems she has with her memory, he said.

Several others who were detained during the crackdown have told friends and family how they were tortured while in custody. Some said they were beaten, shackled and given electric shocks, while others said they were deprived of sleep, forced to take medication, and held in painful stress positions.

Rights lawyer Li Chunfu was diagnosed with schizophrenia after 500 days of detention; the wife of Li Heping, Li Chunfu’s brother and a fellow rights lawyer, hardly recognised her husband when he came home emaciated and grey-haired; lawyer Xie Yang’s detailed and harrowing account of torture grabbed international headlines, leading the European Union to urge China to investigate reports of torture. Xie later withdrew his allegations of being tortured and pleaded guilty in court, though his family and rights groups have said they believe he was forced into discrediting himself.

The claims of torture have upset the families of those still held in custody, especially as they have been denied visiting rights.

Jin Bianling, wife of Jiang Tianyong, a rights lawyer who went missing in November and was later confirmed to be detained, said she was extremely worried as to whether her husband, who had been tortured during previous detentions, would be able to pull through this time.

Xie was transferred to the No. 1 Detention Centre in Changsha, capital of central China’s Hunan province, after being formally arrested with subversion last month.

“That was where Xie Yang was held while being tortured,” Jin said. “They must treat him [Jiang Tianyong] the same if he does not cave in.

“I don’t even know if he’s dead or still alive,” she said, adding that police had not allowed her husband any visitors since being detained.

Jiang’s defence lawyer Chen Jinxue said he had applied to visit Jiang about 10 times, but that every application had been turned down.

Speaking of another of the detained lawyers, Wang Quanzhang, Chen said there had been no word for more than 700 days.

“There has been no news, no photos and no confession videos. Nothing,” he said. “It’s like he evaporated into thin air. We’re all very worried.”

Wang’s wife Li Wenzu has tried several times to complain to China’s top prosecuters' office about the silence surrounding her husband, but has been repeatedly turned away.

The 709 crackdown came as Beijing was pushing for legal reforms to improve its “rule of law” – a phrase that is frequently used by the state media and President Xi Jinping himself. Critics, however, have said that the government’s treatment of the rights lawyers shows the country is heading in the opposite direction.

“Jailing the very people who fight for the rule of law undermines progress towards the stable society the Communist Party claims to want,” said Sophie Richardson, China director of Human Rights Watch.

“As long as the Chinese government treats legal defence work as anti-state activity, confidence in the country’s legal system will remain low.”

William Nee, a China researcher at Amnesty International, said the crackdown has severely damaged China’s reputation as a country that is dedicated to the “rule of law” by drawing lines in the sand and arbitrarily defining “sensitive cases” that lawyers are not allowed to get involved with.

“This is a sort of knock-off rule of law that should alarm everybody in the international community,” he said.

Nonetheless, two years on from the crackdown, legal activists and rights lawyers remain optimistic, saying that the government’s efforts to dismantle the country’s human rights sector through the clampdown had been a “complete failure”.

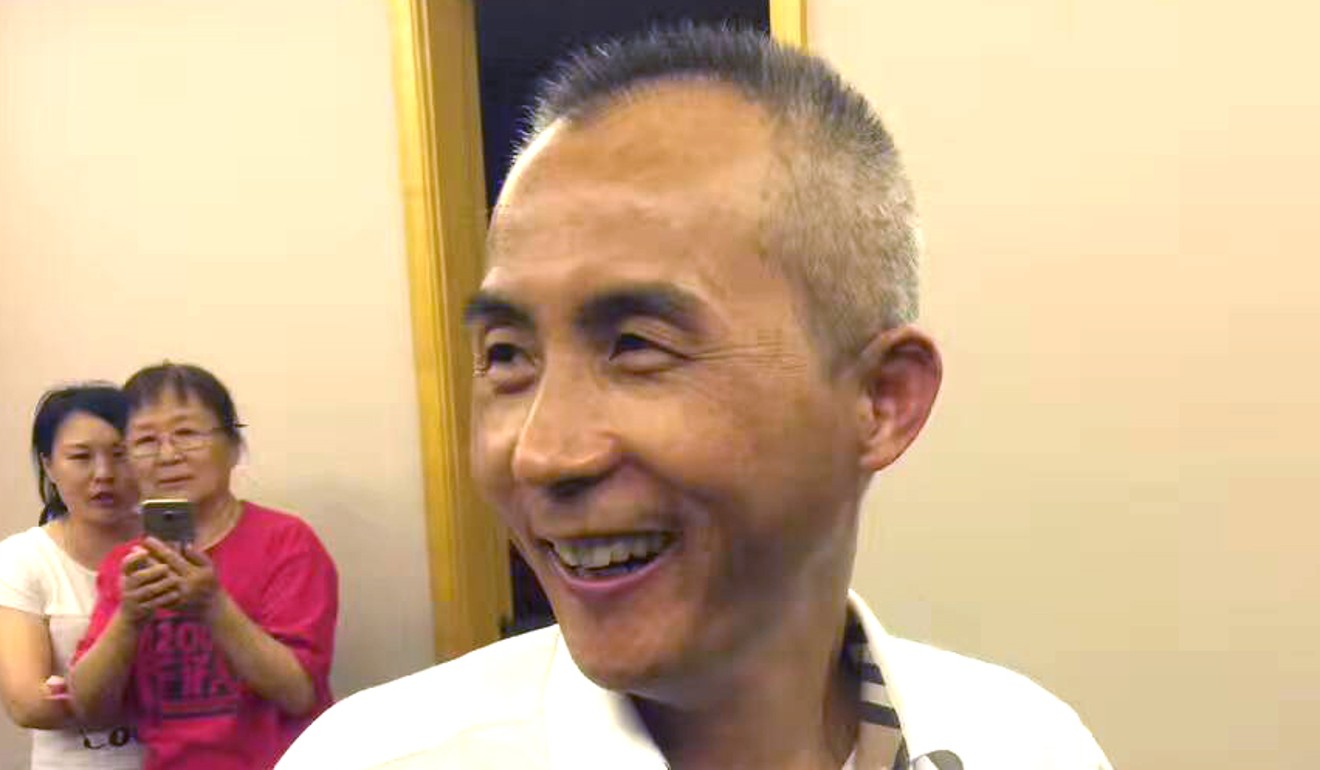

Dr Feng Chongyi, a China watcher from the University of Technology, Sydney, who was recently prevented from leaving China after conducting research on the crackdown, said “709 failed miserably”.

“Not only has Beijing severely damaged its international reputation with this campaign, but the resistance of 709 family members has drawn keen media coverage that has shed light on China’s human rights situation,” he said, adding that many lawyers who used to focus on commercial litigation have now joined the plight.

Teng Biao, a legal activist in exile in the United States, agreed.

“Although human rights lawyers have suffered a harsh setback, the community has not been destroyed and will continue to grow ... we are seeing more young and brave lawyers joining the force,” he said.

Jiang Tianyong’s lawyer, Chen, who is based in the southern city of Guangzhou, said he would not be cowed.

“The authorities did not achieve their goal to intimidate us, but instead has strengthened our faith. I’ll continue to do what I think is the right thing to do: to defend China’s human rights and to achieve China’s democratic transition one day,” he said.

Additional reporting by Mimi Lau