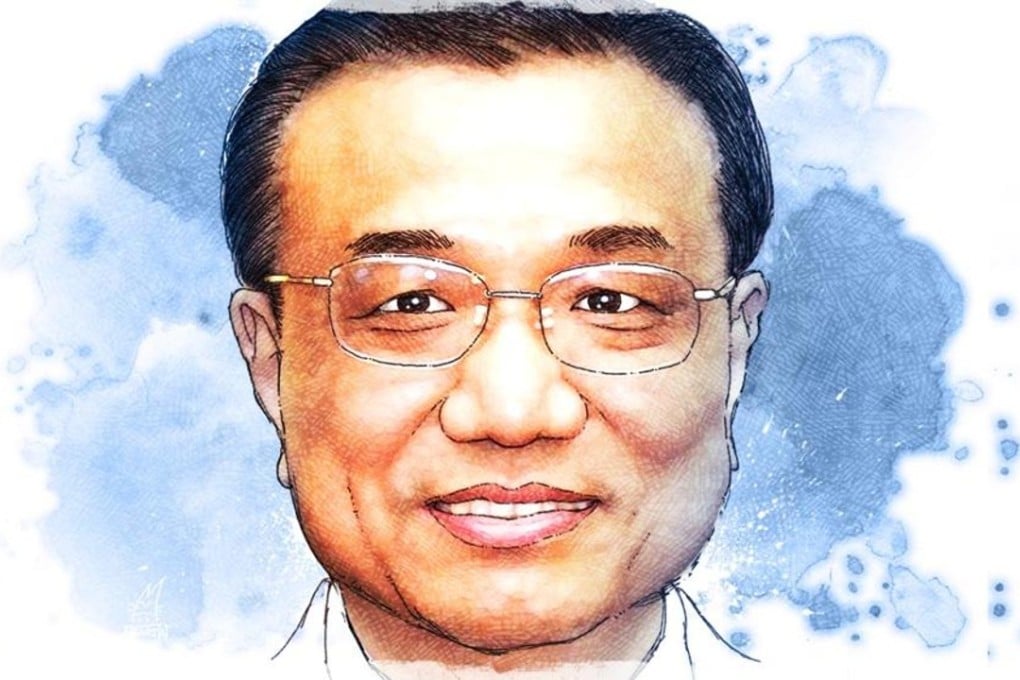

Premier Li’s second term: from ‘Likonomics’ to following orders

With Xi Jinping taking a firm grip on policymaking, the party’s No 2 is likely to focus more on implementing economic decisions rather than making them

China’s Communist Party unveiled its new leadership team on Wednesday. The membership of the party’s supreme decision-making body, the Politburo Standing Committee, remains at seven. Other than Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang, the other five members of the committee are new faces following the retirement of the previous members. The six other Standing Committee members will play a key role in affirming the core leadership of Xi, who has had his name enshrined in the party charter. The party also unveiled the new leadership of the Central Military Commission. Here we look at the key members of Xi’s team.

Li Keqiang will stay as No 2 in the ruling Communist Party but his role as premier is expected to be redefined during President Xi Jinping’s second term – with more of a focus on implementing rather than making economic policy.

The premier is one of the few Chinese leaders who can communicate directly with Western counterparts and deliver speeches in English – he is regarded as one of the best representatives of China’s technocrats who are keen for the country to move up the industrial chain and expand its global footprint.

Li was among the first students admitted to Peking University’s law school – the best in China – when the college entrance exams resumed in 1977 after the Cultural Revolution.

He was a student of professor Gong Xiangrui, an expert on Western constitutional law who studied in Britain in the 1930s. Li went on to earn a doctorate in economics from Peking University.