Out with the technocrats, in with China’s new breed of politicians

Engineers no longer dominate the top echelon of power as the fifth-generation leaders – who studied politics, law and philosophy – take over

Once run by peasants-turned-revolutionaries and then engineers, China is now in the hands of a group of political experts, economists and theorists.

Only a decade ago, eight of the nine top Communist Party leaders studied engineering or natural sciences – the most sought-after majors when the country was struggling to industrialise.

But no one in the newly appointed Politburo Standing Committee, unveiled on Wednesday, belongs to the so-called technocrats, who worked as engineers or natural science researchers before entering the political arena.

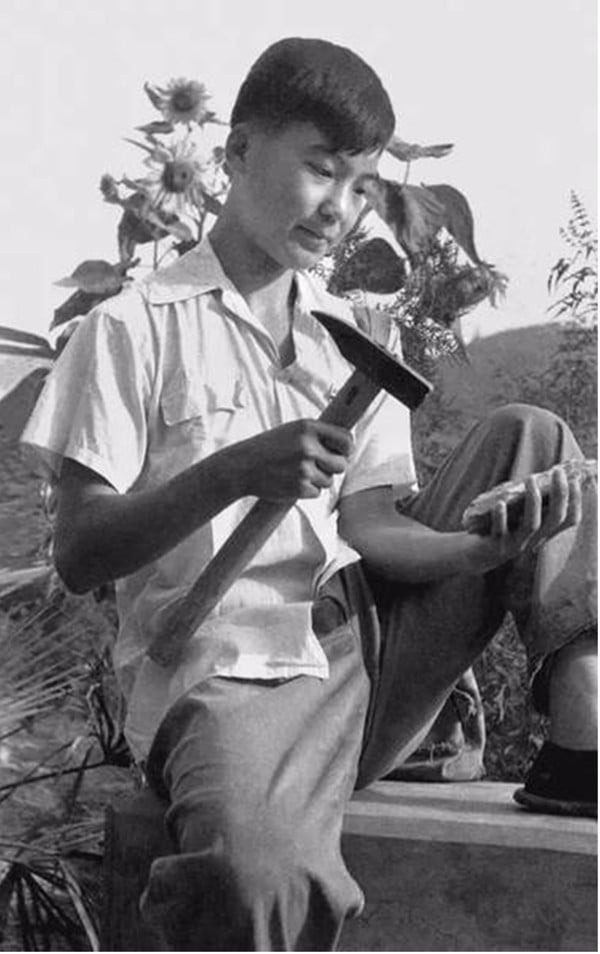

President Xi Jinping, who studied chemical engineering at Tsinghua University, was the only one with such experience, but he went straight to the government after graduation and pursued a higher degree in Marxist theories and political education.

Among his peers, two studied political education for their first degree and the rest majored in management, philosophy, politics or law.

Their education history varies. Wang Yang, who started as a food factory worker, got his first degree in management at a party school in 1992, when he was a mayor in Anhui province.

But in the same year, then 37-year-old Wang Huning was already the head of the international politics department at the prestigious Fudan University.

Communist leaders in the Mao era had largely been peasants and soldiers, but the development in higher education contributed to a rise in technocrat politicians.

To support China’s industrialisation, the party under Mao overhauled mainland universities in the 1950s, mirroring the Soviet Union model by setting up a large number of engineering schools while cutting down on humanities departments.

That meant that from 1997 to 2007, all of the top leaders sitting on the innermost Standing Committee shared an engineering background.

Former president Hu Jintao is a hydraulic engineer while his premier, Wen Jiabao, specialised in geological engineering. Hu’s predecessor Jiang Zemin was trained as an electrical engineer – and did an internship at a Moscow car factory.

But among the fifth-generation leaders – those who were born in the 1950s and went to university after the Cultural Revolution – the engineers no longer dominate.

With a law degree and a PhD in economics from Peking University, when Li Keqiang joined the Standing Committee he was the only member to have studied humanities as an undergraduate.

In fact, during Xi’s first term, the only engineer in the top echelon of power was Yu Zhengsheng, who studied missile guidance but ended up overseeing ethnic minorities and religious affairs.

Tao Yu, a political sociologist at the University of Western Australia, said that for Chinese officials – who spend decades ascending the political ladder – governing experience mattered more than academic background.

“But higher education does have an impact on their rule,” Tao said. “Leaders who went to universities tend to do a better job in reading data and analysing problems. They are very different from the revolutionaries who used to run China.”

The growing prevalence of university education would see more officials with solid professional knowledge and international experience enter Chinese leadership, Tao said.

The younger generation are already working in lower-level governments and state-owned enterprises, where they assist in areas including economic planning and diplomacy.

“They are not yet decision makers, but they’re participating in specific policymaking,” Tao said. “They are playing a bridging role in Xi’s drive to expand China’s global influence.”