Meet the Chinese farmer turned eco-warrior who’s taking on big business

His legal battle with a chemical giant has been running for 16 years, but Wang Enlin, 64, refuses to back down

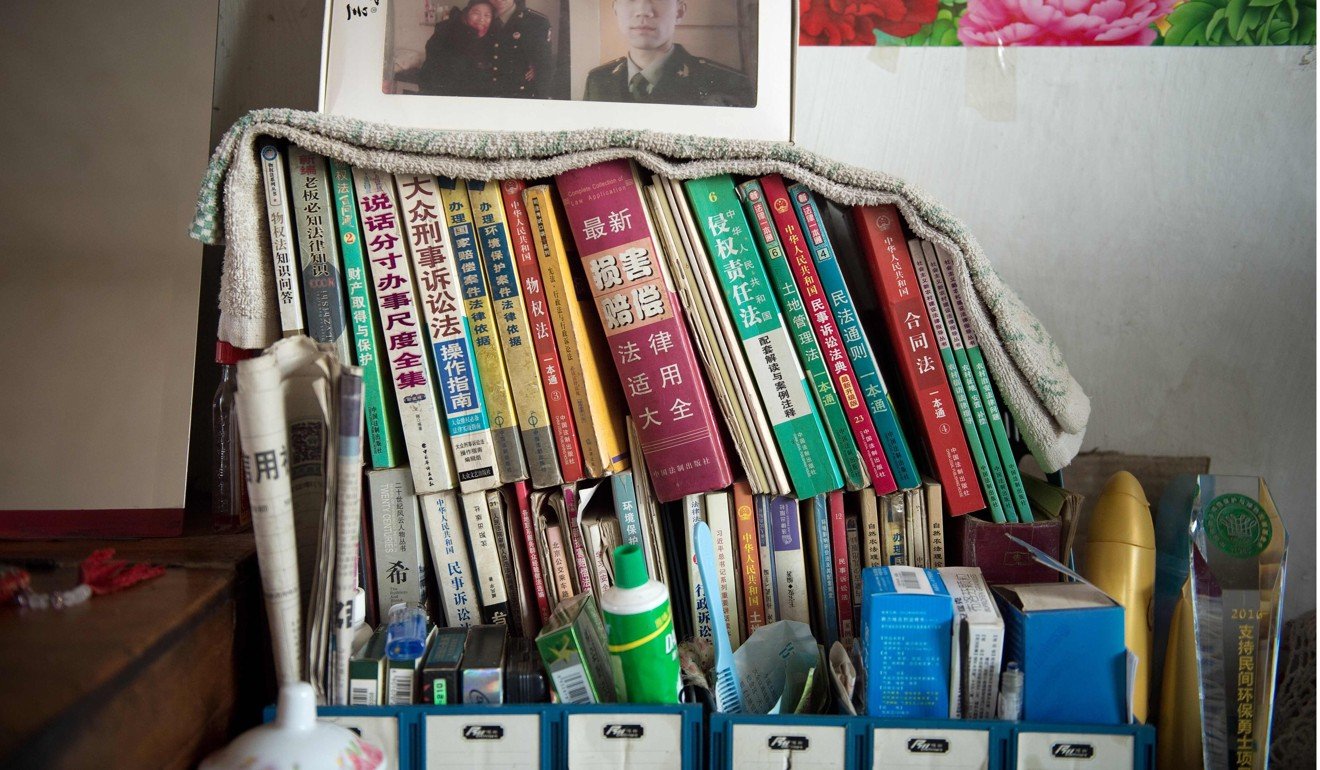

Chinese farmer Wang Enlin, who left school at the age of 10 and taught himself law armed with a single textbook and a dictionary, makes for an unlikely eco-warrior.

Yet the 64-year-old is determined to reap justice as he readies for a fresh battle in his war with a subsidiary of China’s largest chemical firm, which he accuses of polluting and destroying his farmland.

“In China, behind every case of pollution is a case of corruption,” he said of his mission to bring Qihua Chemical Group, also known as Heilongjiang Haohua Chemical, to account.

Wang and other villagers from northeastern Heilongjiang province have sued Qihua, accusing it of contaminating their soil, rendering it useless for growing crops, in a case that has stretched on for more than 16 years.

In February, Wang and his self-styled “Senior Citizen Environmental Protection Team” earned a rare victory when a local court ordered Qihua to clear up their chemical waste site – near the farmers’ land – and pay a total of 820,000 yuan (US$123,000) to compensate for lost harvests in 55 affected rural households.

But that ruling was overturned on appeal, and Wang is now gearing up to fight back on another day in court.

“We will absolutely win. The law is on our side,” Wang said.

His case is testing the possibilities of a national environmental protection law revised in 2015.

The legislation was widely touted as a way to open the courts to public interest environmental damage lawsuits, but has been criticised for poor implementation.

Qihua is a subsidiary of the state-owned ChemChina, the country’s largest chemical company. It specialises in crude oil processing and petroleum products.

Wang’s battle began in 2001, when a village committee leased 28.5 hectares to Qihua for use as a chemical waste dumping ground without the villagers’ consent.

The villagers claim the company failed to take proper pollution control measures.

Wang said he felt forced to teach himself law after realising he lacked the knowledge or resources to take on the might of an industrial giant.

China had just emerged from its Great Famine when Wang left school: “It didn’t matter at the time whether you got an education,” he said. “It wouldn’t change your fate.”

He was well into middle age when he found a textbook on environmental law at a local bookstore. It took him years to understand as he painstakingly looked up unfamiliar terms in a dog-eared dictionary.

After petitioning the local authorities to no avail, he received aid in 2007 from the Centre for Legal Assistance to Pollution Victims, which helped the villagers put together a lawsuit using evidence he had compiled.

A 2013 sampling of mercury levels conducted on the site by the Green Beagle Institute, a Beijing-based charity, found the land was “not suitable for agricultural use”.

The Ministry of Environmental Protection included Qihua in a 2014 list of “major” environmental cases.

But it was still another year before Wang’s case was accepted into China’s justice system.

Prominent environmentalist Ma Jun said that while the litigation process had been streamlined since 2015, pollution lawsuits could still take years to be heard partly because “local governments give some degree of protection to polluting companies”.

Nowadays, Wang prepares his own legal paperwork and hosts daily gatherings at his home for villagers hoping to learn about their rights.

Wang, who suffers from lung problems and requires medicine to help him breathe, accused Qihua of “pretending to be deaf and mute” on the issue.

He said he was frequently visited by police officers urging him to drop the case and stop talking to the media.

Qihua’s lawyers declined to comment on the case.

In September, the Qiqihar Intermediate People’s Court accepted Wang’s request to hear an appeal against the ruling that overturned his initial victory.

“We’re just farmers, without any resources or power,” Wang Baoqin (no relation), a member of Wang Enlin’s senior citizens’ environmental group, said.

“Against the government, we can’t win. Against those corrupt officials, we definitely can’t win. So we decided to take the side road and fight the company.”

According to Rachel Stern, author of Environmental Litigation in China: A Study in Political Ambivalence, the number of new legal cases related to natural resources has increased tenfold over the past decade.

The Supreme People’s Court heard 133,000 such cases last year.

Some complainants have found success. In 2015, a petrol giant was ordered to pay 1.68 million yuan to 21 fishermen whose livelihoods suffered from oil spills.

Qihua’s plant did not appear to be in operation when reporters visited in late August. The land was dry and marked by patches of overgrown grass, no longer the site of a massive waste water pond.

But no crops would grow in the spot again, Wang Baoqin predicted.

“We may not even see justice in our lifetimes,” she said. “We’re doing this for the generations to come.”

.png?itok=arIb17P0)