Controversy over China's DNA experiment underscores East-West ethical divide: scientists

Scientists acknowledge gap in how medical community in East and West view embryos

In the eyes of some mainland scientists, cultural differences might have led to the split of opinion between China and the West over biologists carrying out the first known experiment to alter the genes of human embryos.

A number of leading scientific journals in the West refused to publish the study by researchers at Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, warning that too little was known about altering the human genome, and changes could last for generations.

Critics called for a stop to related studies, but the authors insisted their research posed no ethnical problems, and the study won support from the mainstream scientific community on the mainland.

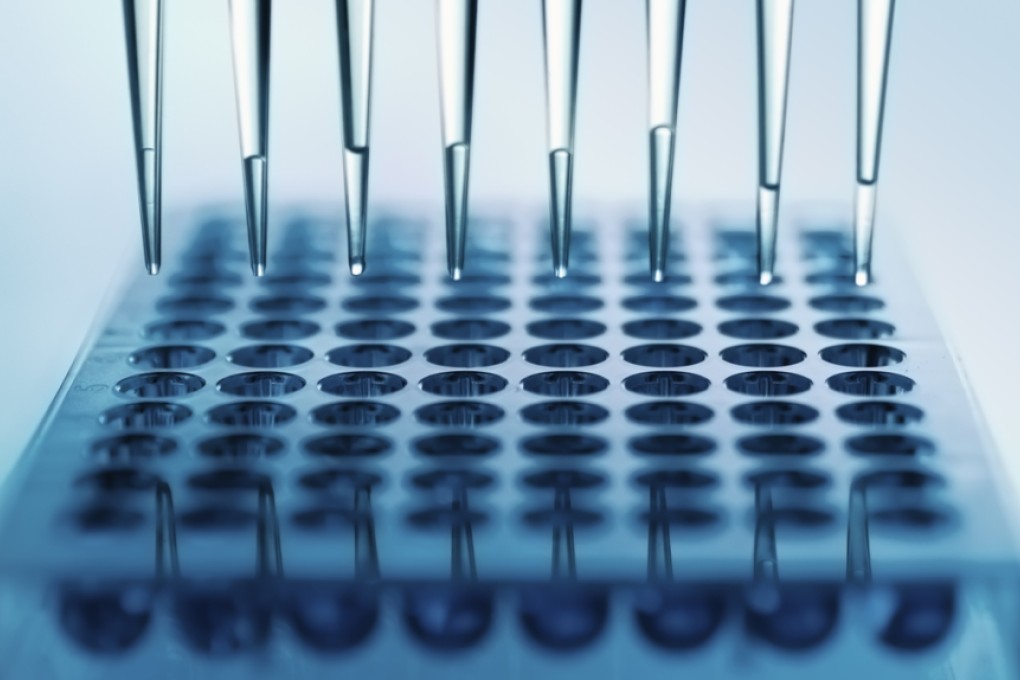

The study by Dr Huang Junjiu's team used embryos that were discarded by hospitals because they had extra chromosomes and would not have developed normally. The researchers used a gene editing method called Crispr in an attempt to "repair" a gene called HBB. It can cause thalassaemia, a blood disease found across southern China. In Guangdong province alone, more than 4,000 newborns are diagnosed with the disease each year, and most die before age 10 without costly, life-long treatment, according provincial health authorities. But the team's attempts to fix the gene on all 85 human embryos failed.

The paper's rejection and subsequent criticism from the West sounded an alarm. Mainland scientists fear these objections may hamper medical advances that could save lives.

The ethical conflict between East and West could be difficult to solve because they are deeply rooted deeply in cultural differences, mainland scientists say.