Where did that rice in your bowl originally come from?

Scientists find more evidence that staple food was first grown in China’s Zhejiang province

A new Chinese study has added weight to Zhejiang province’s claim to be the place where rice was first domesticated.

Many places have claimed that honour in years of heated debate, including the Korean Peninsula, Japan, China, India and Cape York in Australia, but archaeological and genetic evidence unearthed during decades of research pointed to South China as the site of the key grain’s first cultivation.

But precisely where in South China? The provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Hunan and Guangdong all claimed to be the birthplace.

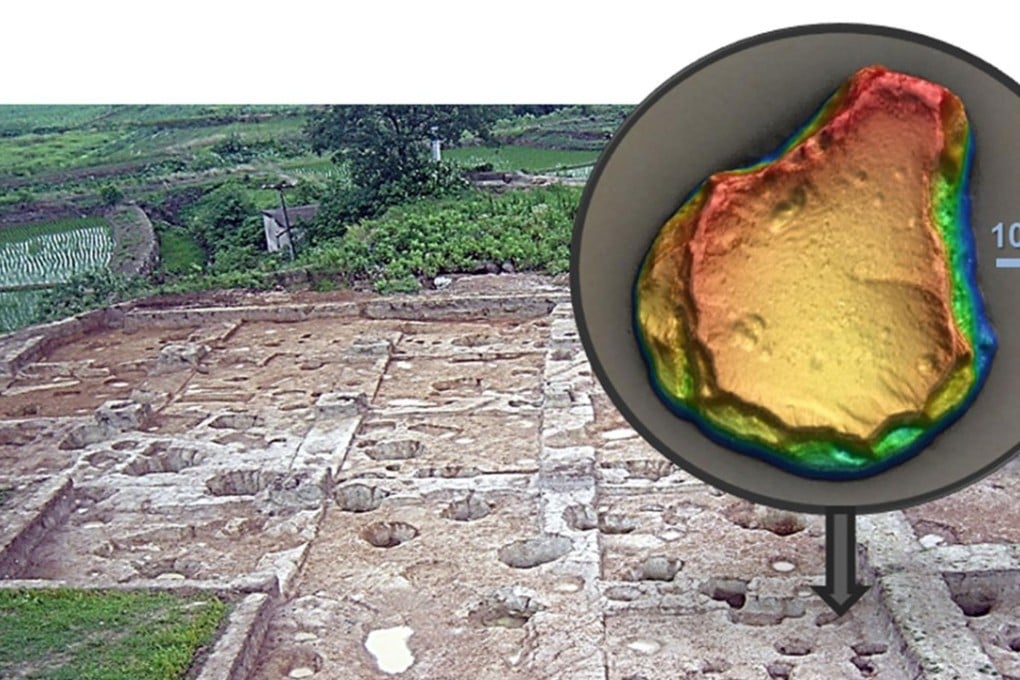

In an article published in PNAS, the official journal of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences in the United States today, a team of mainland Chinese researchers give further credence to suggestions the earliest domestication of rice might have occurred at an archaeological site, Shangshan, on the lower reaches of the Yangtze River in Zhejiang around 10,000 years ago.