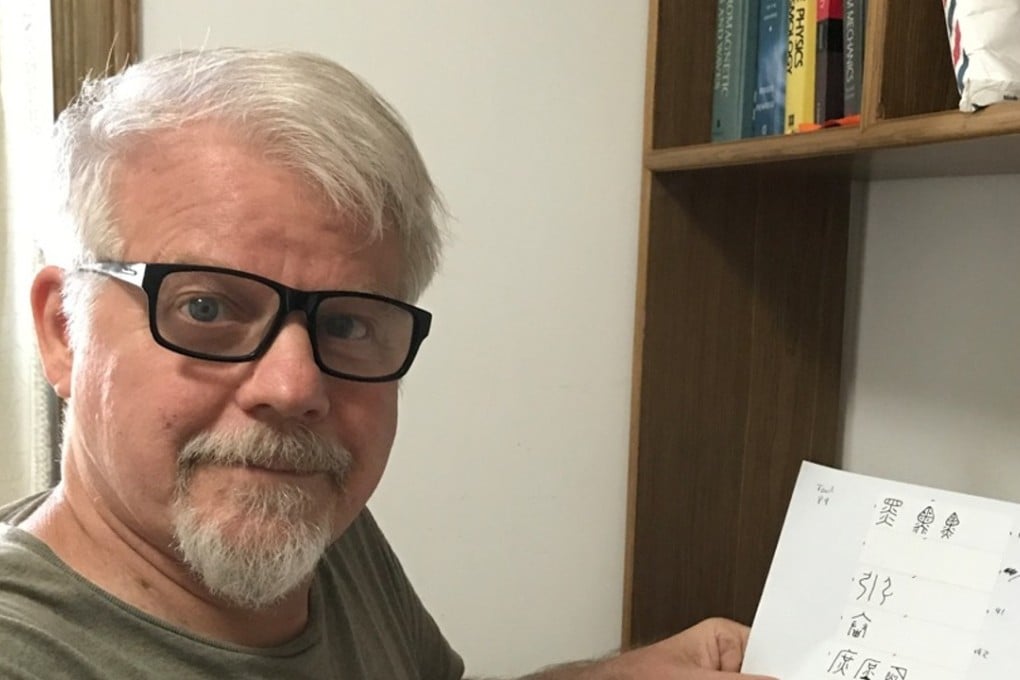

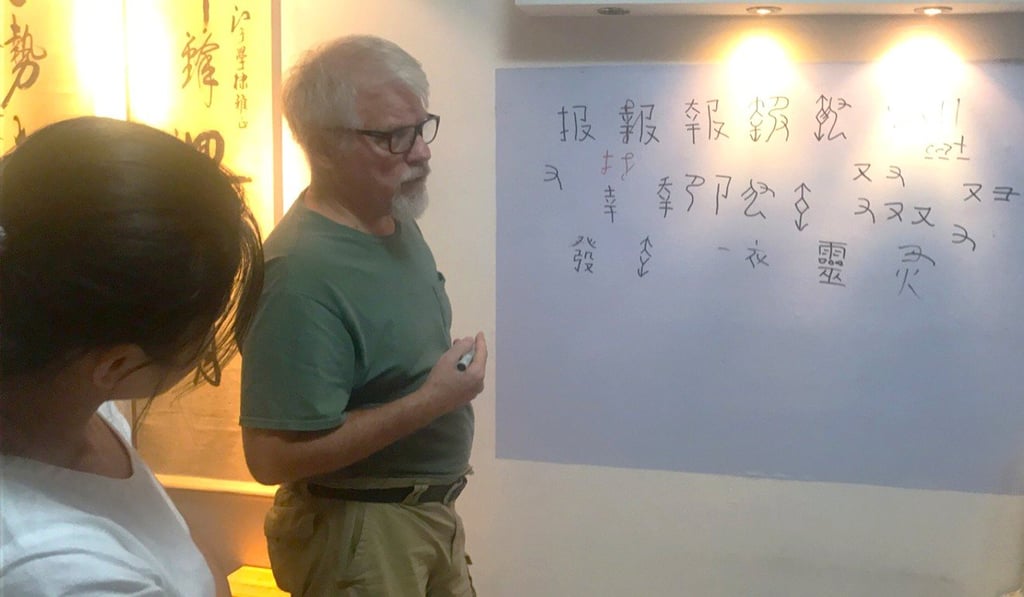

Meet US expatriate ‘Uncle Hanzi’, devoted custodian of Chinese characters

Richard Sears has spent 15 years tending to a website on Chinese etymology that includes ancient formats for nearly 9,000 characters

Had he not taken the hallucinogenic drug LSD at a party in Boston in the early 1970s, Richard Sears may have led a very different life.

Before then, his dream had been to earn enough money to go to Africa. But under the effects of the drug known as “acid”, Sears felt “strongly inspired to learn Chinese”.

Sears, who was born in 1950 and grew up in Medford, Oregon, a northwestern US city with few Chinese people, could not shake the feeling. In 1972, he bought a one-way plane ticket to Taiwan with the goal of learning Chinese.

That was the beginning of a lifelong journey to quench his desire to learn more – and ultimately to impart knowledge to others – about the characters that underpin a very old language.

Over the next four decades, Sears took on various jobs, ranging from English teacher in Taiwan to physics researcher at a national lab in Oregon to computer programmer in Silicon Valley. Nonetheless, his primary passion remained the study of ancient Chinese characters.

He has spent the past 15 years tending to a website – Chineseetymology.org – dedicated to Chinese etymology, which now encompasses 100,000 ancient formats for nearly 9,000 Chinese characters.