China’s ‘elderly vagabonds’ sacrifice retirement to care for grandchildren

Elderly migrants who leave their homes to attend to needs of grandkids find themselves isolated in China’s megacities

Sun Yulan’s plan for a peaceful retirement took an unexpected turn five years ago when her granddaughter was born.

Answering her son and daughter-in-law’s call for live-in help with the newborn, Sun and her husband willingly traded the relatively free life they had enjoyed in their 120 square metre flat in Anshan for a more regimented existence of cleaning, cooking and sending children off to school in eastern Shanghai.

After three years, Sun and her husband planned to move back to their flat and pursue their retirement in earnest. But the birth of their grandson has kept the couple in their son’s house and continuing to be the anchor of the household.

The arrangement which once brought satisfaction has become a source of frustration.

“My daughter-in-law seldom talks to me except to leave dirty laundry,” Sun said. “We are like unpaid maids, but what can we do? It’s so expensive to hire a nanny in Shanghai.”

Nearly half of the elderly migrants in China’s first-tier cities have sacrificed their retirement and left their homes to care for children or grandchildren. Researchers say this trend represents a shift in family and social structures and places the elderly migrants at risk of isolation.

Dubbed the “elderly vagabonds”, elderly migrants account for 7.2 per cent of China’s migrant population of 247 million. Forty-three per cent of that group leave home to take care of children or grandchildren, according to figures from the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

The rate is even higher in economically developed cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, where more than 54 per cent of elderly migrants moved to the cities of their children to take care of them, according to a report by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

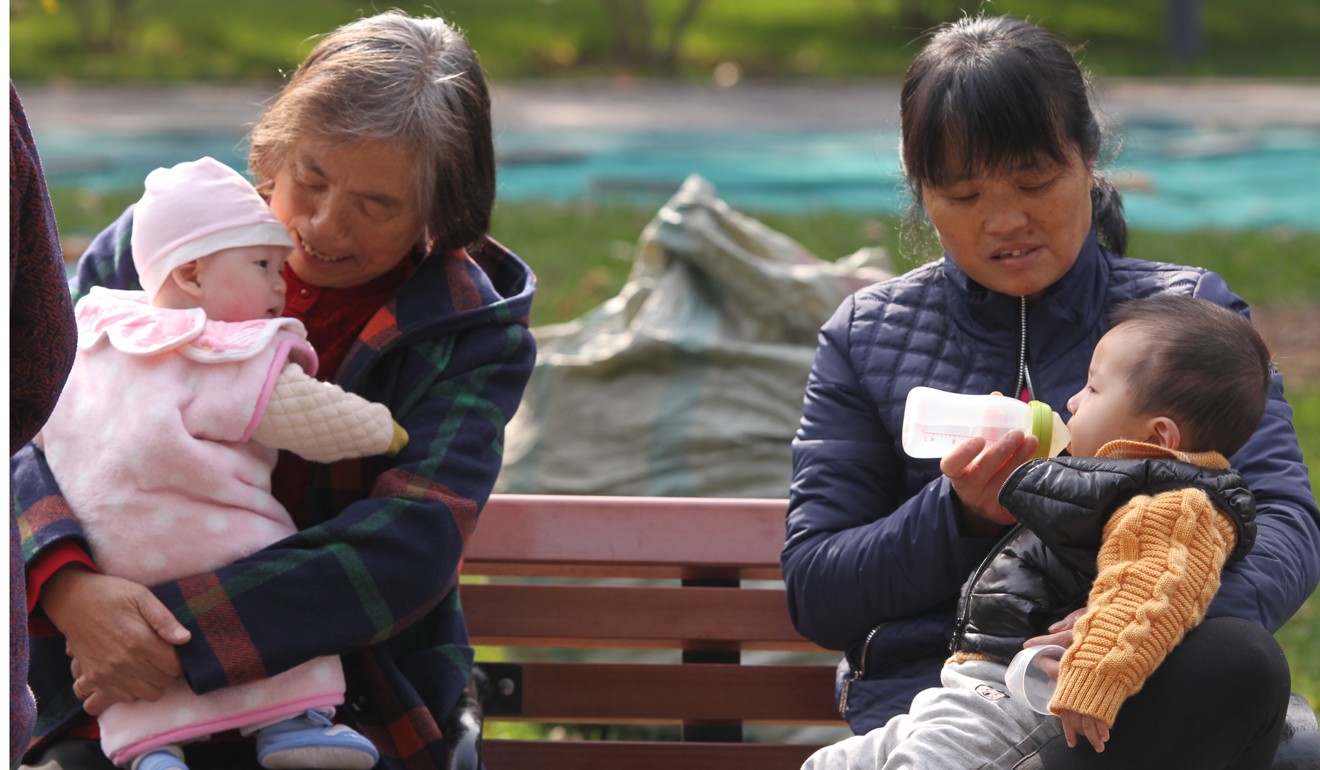

These senior citizens help take care of newborn babies, accompany schoolchildren to extracurricular activities and shoulder domestic chores such as cooking and cleaning.

Liu Yana, a Capital Normal University professor who has researched these elderly migrants in Beijing, found that many not only endured physical hardship from working long hours but were also troubled by loneliness and had difficulty integrating into society.

Even those who have lived in the cities for years are often only familiar with the routes to local schools and markets, and live an isolated life with few friends to talk to.

Liu’s research found that few of the elderly migrants who came to Beijing to look after grandchildren socialised with neighbours or joined community activities. Most had at best a nodding acquaintance with a few neighbours.

Sun said she had felt lost since moving to Shanghai. Her son and daughter-in-law are both doctors and spend little time at home. When they do come home they focus on their own work or recreation.

Taking care of everything with her husband from cleaning, cooking and washing to sending children to school left her feeling upset and exhausted, Sun said.

Sun, who cannot speak the local dialect, said she found the city too big and different from the small city she and her husband had known their whole lives.

Zhou Fanggyun, 65, used to have a colourful life back in Xian, Shaanxi province. In the mornings she would play ping-pong, followed by a nap and television in the afternoon and square dancing in the evening. That lasted until she and her husband moved to Beijing 3½ years ago to take care of their granddaughter.

Her new routine, from 5.30am to whenever the mother finished work, centred on the principle of “baby first, us afterwards”, from meals to rest.

Even after years of living in Beijing, Zhou only knows the route to the nearby park, the schools and supermarkets.

“I know nobody and I speak Putonghua in a heavy Shaanxi accent. I am worried local senior citizens might look down upon me,” Zhou said. “Luckily I have my husband with me.”

It is no easy task for three generations to live harmoniously under the same roof, or crammed into a small flat.

Zhou said she had not always seen eye-to-eye with her son and his wife on child care. To maintain a smooth relationship, she never made any decisions and only did what her daughter-in-law asked her to do.

“I ask their opinions [on a range of things,] from wearing clothes to [giving the proper medication] when the child is sick. The mother signed up for some classes, so I sent the child to the classes and picked her up as they wanted. I don’t get too involved in making decisions,” Zhou said.

According to Liu’s study, elderly migrants who leave their familiar environment and social circle not only have to adapt to a new way of life but also need to establish new ties with neighbours and friends.

Although it was up to the individual to choose whether to stay in an adopted city, it was only “fair” to have government policies and community support to help elderly migrants integrate and acquire a sense of belonging, the academic said.

“It should be guided by the government but not [be] entirely dependent on government,” Liu said. “It is a two-way street. Individuals count, too.”

Individuals must be motivated to socially integrate into their new cities, she said; others must create a supportive environment for them to do so.

Liu said the growing number of elderly migrants had presented city administrators with a great challenge and new initiatives had been launched to help them integrate better. For example, inpatient medical bills can now be settled directly in elderly migrants’ adopted cities under the public medical insurance scheme, and they can collect their pensions without having to return to their hometowns.

“It is not perfect but the direction is making life for the migrants more convenient,” Liu said.

For some, the inconvenience is not as important as being with their grandchildren.

Lin Ying, 55, a retired former hospital administrator from Jiujiang, Jiangxi province, gets up before 6am to prepare food for her 15-month-old granddaughter so her daughter can sleep longer.

After breakfast, Lin takes the tot on a daily outing to the park. They return home for lunch and a nap before going out again in the afternoon. In the evening she plays with the girl, reads books to her and teaches her to recite poems.

“The work is fine, really, as long as I am being useful,” Lin said. “My daughter feels much at ease having her mother rather than a stranger taking care of the child. I just wish my husband would retire soon so he could join me in Beijing.”

Huang Zichang, 61, from Hefei, Anhui province, said he was only too happy to close his convenience store back home and come to Beijing to take care of his grandson.

The eight-month-old boy gets on well with his grandparents and Huang said he appreciated the opportunity.

“I have been here for less than two months now,” he said. “So far so good, and I don’t think of leaving at all.”