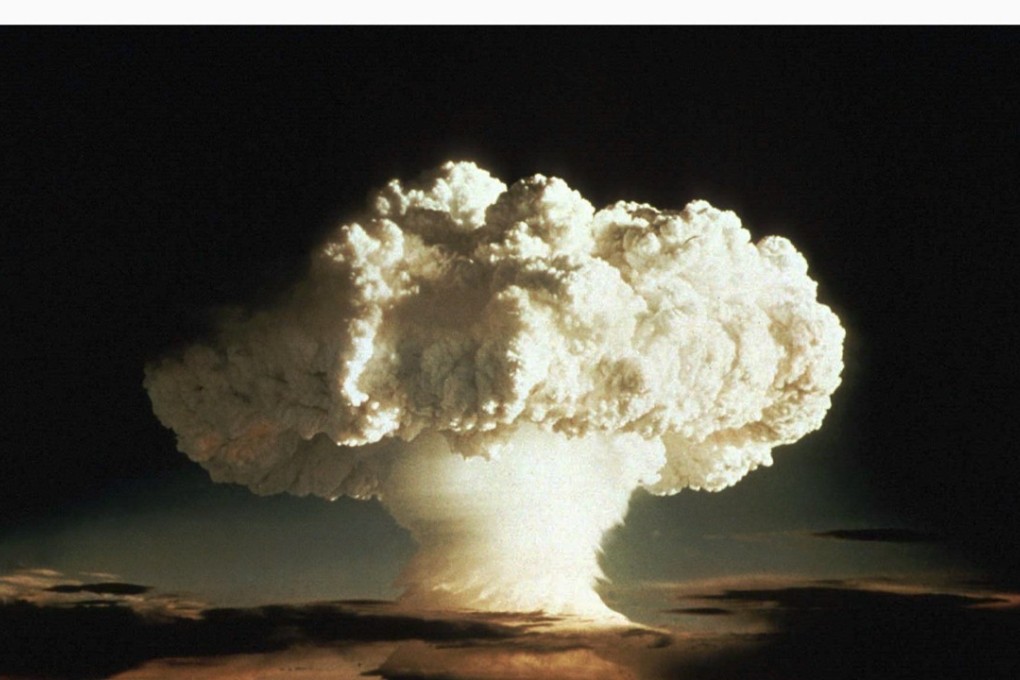

China steps up pace in new nuclear arms race with US and Russia as experts warn of rising risk of conflict

Chinese scientists are running simulated tests at a faster rate than America as world’s leading powers develop arsenal of ‘usable’ next-generation weapons

China is aggressively developing its next generation of nuclear weapons, conducting an average of five tests a month to simulate nuclear blasts, according to a major Chinese weapons research institute.

Its number of simulated tests has in recent years outpaced that of the United States, which conducts them less than once a month on average.

Between September 2014 and last December, China carried out around 200 laboratory experiments to simulate the extreme physics of a nuclear blast, the China Academy of Engineering Physics reported in a document released by the government earlier this year and reviewed by the South China Morning Post this month.

In comparison, the US carried out only 50 such tests between 2012 and 2017 – or about 10 a year – according to the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

As China joins the US and Russia in pursuing more targeted nuclear weapons as a deterrent against potential threats, the looming arms race would in fact serve the opposite purpose by increasing the risk of a nuclear conflict, experts warn.

Pentagon officials have said the US wants its enemies to believe it might actually use its new-generation weapons, such as smaller, smarter tactical warheads designed to limit damage by destroying only specific targets.