How bike ride from Hong Kong to Paris changed four young men

12,000-kilometre bike ride from Hong Kong to Paris gives foursome indelible memories, some painful, and a fresh perspective on life

They knew the destination was within touching distance and a few more hours of easy cycling on flat roads would bring to an end 7½ months of sweat and bustle. What remained would be a sense of achievement and sweet memories they could take pride in for life.

"We are here, finally," said Law Yip-man, 25, sounding relaxed and calm, as he thought back to the pain and gain from the monumental 12,000 kilometre journey from their home city halfway across the globe.

Law, who was a construction supervisor and developed a passion for backpacking travel under the influence of his mother, initiated the journey last year after being inspired by a Taiwanese computer engineer who had cycled from Beijing to Paris to promote environmental protection.

"I don't want my life to be bound by work. Why can't we achieve something different that can make us proud for life?" Law said.

His like-minded friends Taylor Chung Tai-loi, 24, a graduate in policy studies and administration, and adventure coach Prince Wong Tze-kin, 22, embraced the plan. Quantity surveyor Tim Yu Tin-yu, 27, also quit his job to join after learning of the plan in an online forum.

Together, they formed "Bike for Another Choice", which aims to explore alternative life goals and advocate cycling as a way of protecting the environment.

None of the quartet had taken a cycling tour before. They took seven months to plan the route, prepare equipment, secure sponsorship and undergo intensive training before setting off in May.

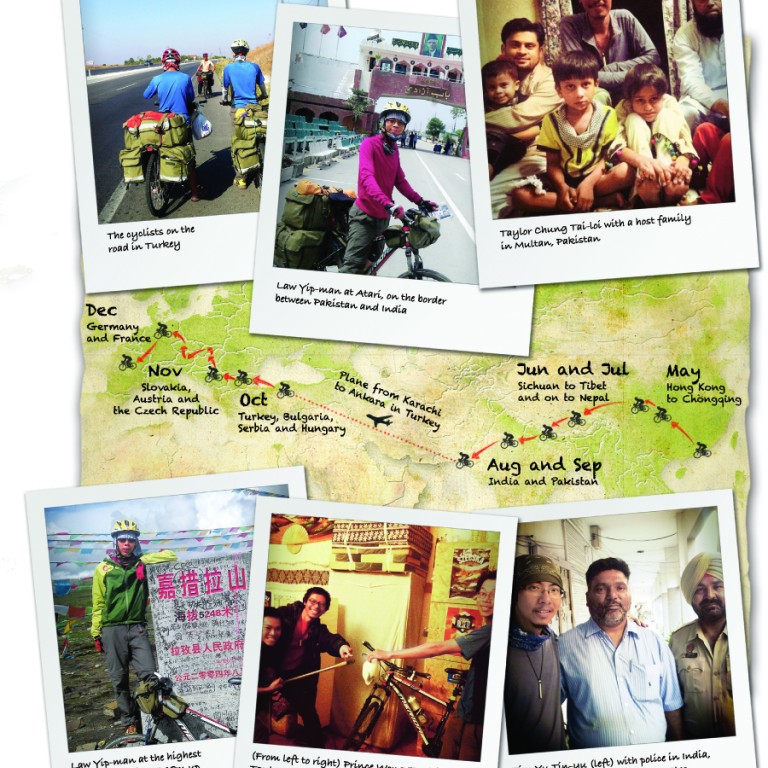

They had planned to ride through Sichuan , Tibet, Nepal, India, Pakistan and Turkey and then head to central Europe. They had to bypass Iran by air because they could not obtain entry visas.

"I don't think we have to be athletes to accomplish this trip. What it takes most is willpower," Law had said before departure. Soon they realised they would need plenty of qualities besides determination to keep them moving forward.

Fatigue and sickness restricted them to a slow start. What's more, within three days the quartet began to question whether they were embarking on the adventure with the right partners.

Chung and Yu quarrelled over the pace. Yu was accused of bringing along heavy philosophy books that kept him lagging behind. He later posted one book back home and promised to finish another during the journey - but his teammates joked that the promise was never honoured.

In fact, the quartet seldom cycled as a group but gathered at checkpoints.

"We got lost quite frequently," Wong said.

The first test of their physical prowess came after a month as they encountered the steep and winding road from Sichuan to Tibet.

The Sichuan-Tibet Highway is a major challenge, as cyclists have to cross 14 mountain passes at altitudes of 4,000 to 5,000 metres.

They climbed continuously for 26 kilometres in a single day to reach one point more than 5,000 metres high. The highway is often blocked by landslides or a morass of thick mud after rain.

"Many travellers were surprised to learn we were going to Paris, and some were sceptical of whether we could even reach Tibet with the heavy luggage," Wong said.

Totalling up their kit - including cameras and laptops to record their journey on their weblog, buckets for washing clothes and their bicycles - each cyclist's gear weighed about 40kg.

Along the popular route to Tibet, they met travellers from all walks of life, from a cyclist in his 50s suffering from liver cancer to a People's Liberation Army veteran who had walked all over the mainland. Their sense of humour and optimism helped relieve the tiring, frustrating and seemingly endless climbs.

"When the road was blocked by landslides and the army was helping us to clear the pathway, we cheered them up by dancing topless," Chung recalled.

But that feel-good factor evaporated after they arrived in India in August. They spent a month enduring scorching heat and sleepless nights under attack by mosquitoes, and rode on rugged and dusty roads. They often found themselves surrounded by curious crowds while resting in packed, messy towns. They were even overcharged by roadside food vendors.

"I would have ridden around the clock to leave the place if I could," Chung said. To make matters worse, their equipment was often damaged on the rugged roads, forcing them to hitchhike or take trains instead.

The quartet would have preferred physical injury to coping with damage to their bikes.

"A physical injury would recover by itself. However, if the bike broke down in the middle of nowhere, there was nothing we could do," Chung said. "When someone fell, the first thing we asked was whether the bike - not the teammate - was all right."

But physical danger was never far away. In Nepal, Law once almost slipped into a fast-flowing stream, only to stop on a ledge. "I couldn't speak for a few minutes. I thought I could have died there," he recalled.

No pain, no gain. The journey in India was the period they looked back on most often, although it was much tougher than they had expected.

"We had no way back there, all we could do was to keep going," Law said.

They did enjoy meeting friendly families who put them up in India, but they also came face to face with tragedy when they saw a girl who had been struck by a car.

"There was nothing we could do when a life was at stake. The town was so remote that no medical staff could have arrived in time to save the girl," Wong said.

"When everyone is talking about how tough life could be in India, what is a better way to feel it in person than by riding through alleys in the rarely visited and the poorest towns?"

Autumn had arrived by the time the group made it to Europe. It should have been the most enjoyable leg, with better road conditions allowing them to ride up to 100 kilometres a day, with time to visit historic towns and a chance to unwind in luxury hotels of a sponsor.

I don't want my life to be bound by work. Why can't we achieve something different that can make us proud for life?

But the worst experience came one chilly late-November morning in Freiburg, on the edge of Germany's Black Forest. As they rested in their tents, Wong's and Yu's bags were stolen, including all of the pictures and videos they had taken on the road. The pair even caught a glimpse of the thieves, but couldn't move quickly enough to catch them.

"That was heartbreaking. My journey had become empty and all the memories seem to have gone suddenly. I feel like I have never been on this journey," Wong said, adding sadly that their plan to publish a book would be affected.

Injuries also forced some of them to abandon their bicycles for part of the route in Germany and France. Yu hurt his foot trying to catch the Freiburg thieves, while Wong and Law were in serious pain as their knees buckled under months of hard work.

December snowstorms in Europe also delayed them, and two had to cycle through sleet overnight in temperatures of minus 8 degrees Celsius to reach their destination on time. "We could not even drink water that night because the water bottle was frozen," recalled Chung.

The quartet eventually met up in Reims to ride the final 150 kilometres to their destination.

And there they were, sitting comfortably in a French restaurant celebrating the end of a life-changing journey. Elated and satisfied, Law said proudly that the journey was not as difficult as they had thought. But there was also a sense of loss, with the realisation that they would not be taking to their bikes the next day.

Asked if they would take off for another cycling adventure in the near future, the answer was straight, simple and unanimous: "No." But that doesn't mean their journey is over.

Yu said he would focus on preparing the book, and then look into what kind of possibilities might come up - just as he stumbled into this adventure.

Chung said the long but mechanical exercise of pedalling had allowed him to consider his life and plan ahead. He said he would study more and hoped to educate younger generations.

Law and Wong dream of opening a hostel along the Sichuan-Tibet Highway.

"I enjoyed staying in hostels and also understand what kinds of difficulties the long-term travellers would have encountered on the road. Therefore I want to offer my help," Wong said.

Law said: "Imagine every traveller marking the route of their journey on a world map with different colours, and what a beautiful picture it could be".

Wong added: "When other young people read the stories, I hope they understand dreams should not necessarily be limited by work or other constraints."

The Eiffel Tower might be the end point of their cycling epic, but all agree that after 12,000 kilometres of endurance and soul-searching they are better prepared to set off on any other adventure they encounter in life.