Book sheds light on Hong Kong's war tribunals

A new book by a legal scholar offers rare insight into the military prosecutions of Japanese soldiers in the city after the second world war

Memories of the cruelty of the Japanese forces in Hong Kong have faded over time - and even less is known about the aftermath of the city's second world war occupation.

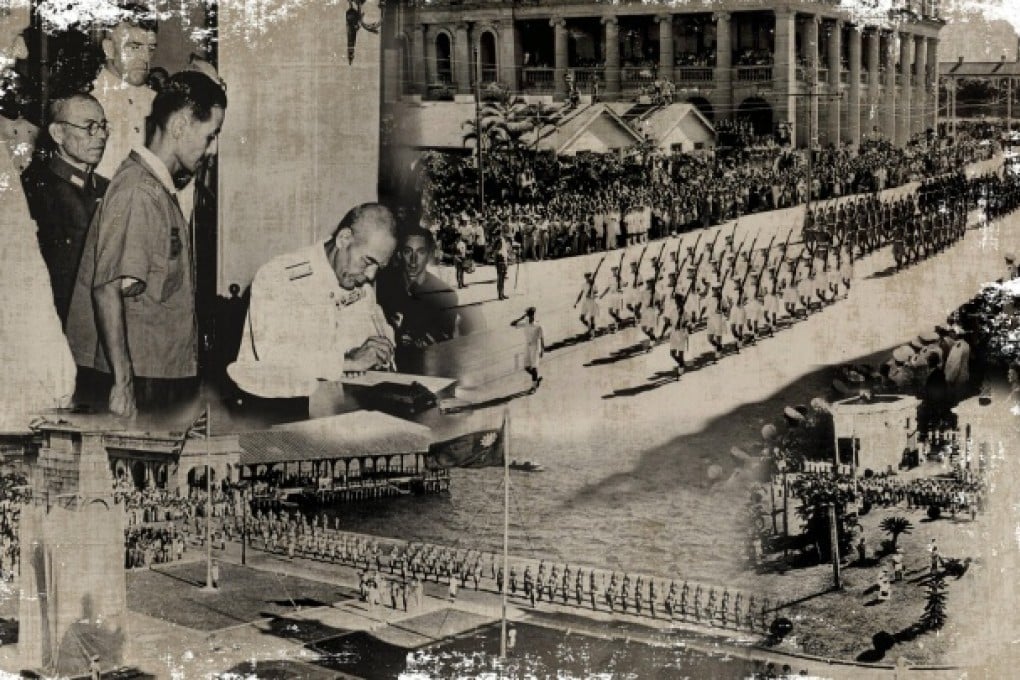

Between March 28, 1946, and December 20, 1948, four British military tribunals tried war crime cases from across Hong Kong, Kowloon and the New Territories. They also heard cases involving war crimes committed in Taiwan, the mainland cities of Huizhou, Guangdong (the city was then known as Waichow), as well as Japan itself and on the high seas.

Professor Suzannah Linton, a former academic at the University of Hong Kong, will offer insight into this forgotten period in her book Hong Kong's War Crimes Trials, to be published in August.

As well as shedding light on the trial themselves and reminding the world of the brutality of the Japanese campaign in Asia, Linton explores key issues in international law that the tribunals raised. They were part of a radical and historic shift towards individual criminal responsibility that had been made Allied policy during the war years, and which was put into practice in Europe and Asia when the war was over.

Thousands of Japanese were tried in Asia, whether by the British, Australians, Chinese or Dutch. Of these, 123 were tried by the British in Hong Kong. Linton believes these cases were part of a much neglected Asian tapestry that has become part of the bigger global picture.