Filibuster in Hong Kong's legislative assembly divides lawmakers, public

The use of delaying tactics by radical lawmakers in Legco in an attempt to block a budget bill has divided both politicians and the public

The original filibusters were pirates, not politicians, terrorising the cities of the West Indies and inciting revolts in Latin America.

Since the term was first applied to politicians in the United States in the 19th century, those who have engaged in the practice have, rather like the pirates of old, been portrayed alternately as swashbuckling heroes providing an essential check and balance on power or villains intent on wrecking civilised society.

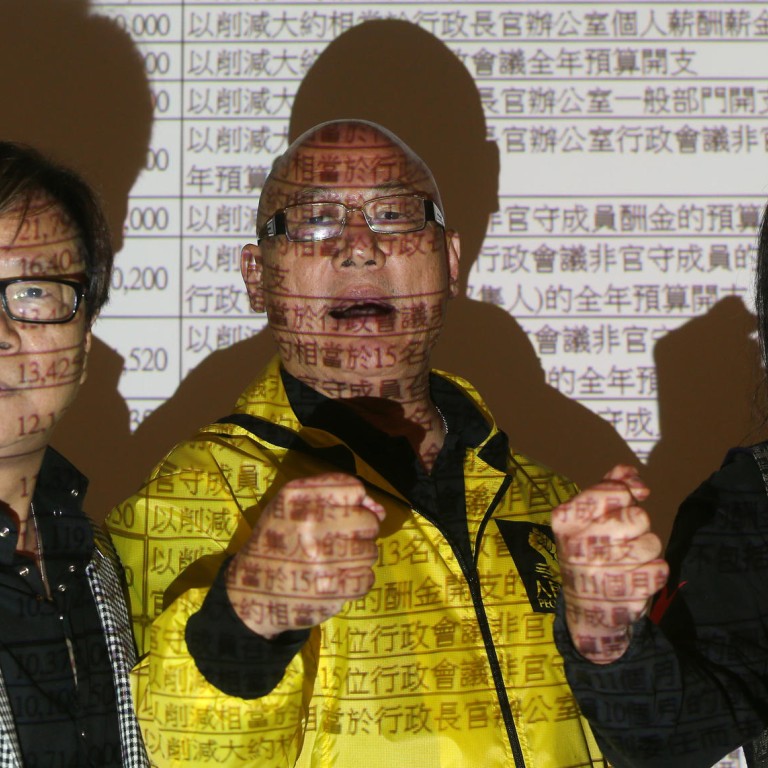

In Hong Kong, a recent filibuster led by radical lawmakers, including "Long Hair" Leung Kwok-hung - a man who might not look out of place swinging across the foredeck of a Spanish galleon, cutlass in mouth - has seen a new twist in the tactic.

While previous filibusters have seen lawmakers attempt to talk out specific bills, Leung and allies Wong Yuk-man, Albert Chan Wai-yip and Raymond Chan Chi-chuen wanted to derail a vote on the budget in order to push for the implementation of a universal pension.

The manoeuvre, eventually cut short by the Legco president, led lawmakers from all sides to question whether the filibuster should continue to exist as a "last resort" option.

Civic Party lawmaker Ronny Tong Ka-wah fears that use of such delaying tactics in the Legislative Council could backfire, giving rise to more restrictions on legislators' power. He believes a fully democratic legislature is the ultimate solution to filibustering, and that a lawmaker's right to filibuster should be protected until universal suffrage is achieved.

Beijing loyalist lawmaker Paul Tse Wai-chun disagrees. He says public opinion remains the most powerful tool in the legislature's armoury, and meaningless filibustering should go.

The Beijing-loyalist camp deplores filibustering, especially after radicals used the tactic last summer to derail Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying's controversial plan to restructure his administration. But it was, in fact Beijing loyalists who first introduced filibustering to Hong Kong 14 years ago.

In 1999, when lawmakers debated the dissolution of the urban and regional councils, lawmakers from the pro-government Democratic Alliance for Betterment of Hong Kong launched a filibuster to help passage of a government proposal to shut down the two councils.

A decade later the boot was on the other foot when pan-democrats filibustered in an attempt to block funding for a HK$66.9 billion high-speed railway project from West Kowloon to Shenzhen. The attempt failed and funding was endorsed in January 2010, despite a public outcry.

Democrat Wu Chi-wai, elected to Legco last year, said he used to regard filibustering as a vital weapon, until his radical allies used it to try to block the budget bill.

"Originally I thought filibustering was necessary, but [now I believe] we must also consider our bigger causes," Wu said. "We are fighting for many things - the most important of all being a democratic system and our opposition to [possible] national security legislation … if a filibuster is used in inappropriate situations, you are just giving more power to the Legco president."

He was referring to the Legco rules of procedure, which make no mention of the handling of filibusters, but empower the president to make decisions "if he thinks fit" and to "be guided by the practice and procedure of other legislatures". Legco chief Jasper Tsang Yok-sing invoked that power last year to kill a 33-hour filibuster attempt over a bill to ban lawmakers who resign from standing for election in the following six months. He did so again to cut short the filibuster over the budget bill last week.

Tong echoed Wu's view that the latest filibuster might have been ill-advised.

"In foreign countries, filibustering is used usually to block a bill from going through, and it is relatively rare to employ it in a fight for a policy initiative," Tong said, adding "if you can use it to fight for one measure, are you going to use it for all [causes] on your agenda?"

Tong worries that if filibusters are used frequently, people will tend to think the Legco president is justified in using his powers to end them.

"It could weaken a lawmaker's basic right indirectly," he said.

Tong and Wu, a veteran Wong Tai Sin district councillor, believe there are more filibusters to come, but say they should be used only in matters that are close to the hearts and minds of the public.

Taking the radicals' call for a universal pension scheme as an example, Wu said, "It is difficult to explain to the people … as they told me 'of course a universal pension is good', but knowing that it will not come immediately, they might have to face some imminent consequences" if a budget is not passed and the government is left hamstrung.

The voters seem to be in agreement.

Timothy Chan, 30, a bank salesman, is a pan-democrat supporter and backs a universal pension. But he is not impressed by use of the filibuster.

"It seems that the delaying tactics have only forced the administration to give up on doing things, but not forced them to do anything," Chan said.

Brenda Pang, from Yuen Long, disagrees with the radicals' tactics because it could have serious consequences and "affect other Legco matters".

Both say the legislature is "inefficient and not pragmatic".

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word filibuster originated from the late 16th century Dutch , which means "freebooter". It later referred to "pirates who pillaged the Spanish colonies in the West Indies in the 17th century, adventurers who incited revolution in various Latin American states in the mid-19th century, or a person who engages in unauthorised warfare against a foreign state".

The word was first used in North America in the late 19th century to refer to obstructive acts in a legislative assembly. Much like in Hong Kong, the question of whether and when a filibuster is justified remains vexed. Parties who gladly use the tactic in opposition tend to become opponents when holding power.

Tse suggested that the radicals had abused the filibuster to such an extent that it had become a "terrorist device".

"It has to be used reasonably … they were trying to destroy the entire budget unless the government surrendered on a policy matter.

"[They have] deviated from the original nature of filibustering," Tse said, warning that Legco's reputation would suffer.

However, Tong believes that the administration bears no small part in responsibility for the filibustering saga "because the government has been raising the bargaining chips" instead of negotiating.

He suggested that instead of celebrating an end to filibustering, it's time for the chief executive and his aides to think about what is wrong with Hong Kong.

"Why, when those people - who publicised that they would use filibuster [tactics] - contested the [Legco] election last year, were they elected with a large amount of votes? It reflects that people have completely lost confidence in our system," Tong said.

"As long as we don't have a truly representative legislature, [lawmakers] will feel the urge, [even] with unusual means, to fight for what we believe is just. It is a vicious circle."