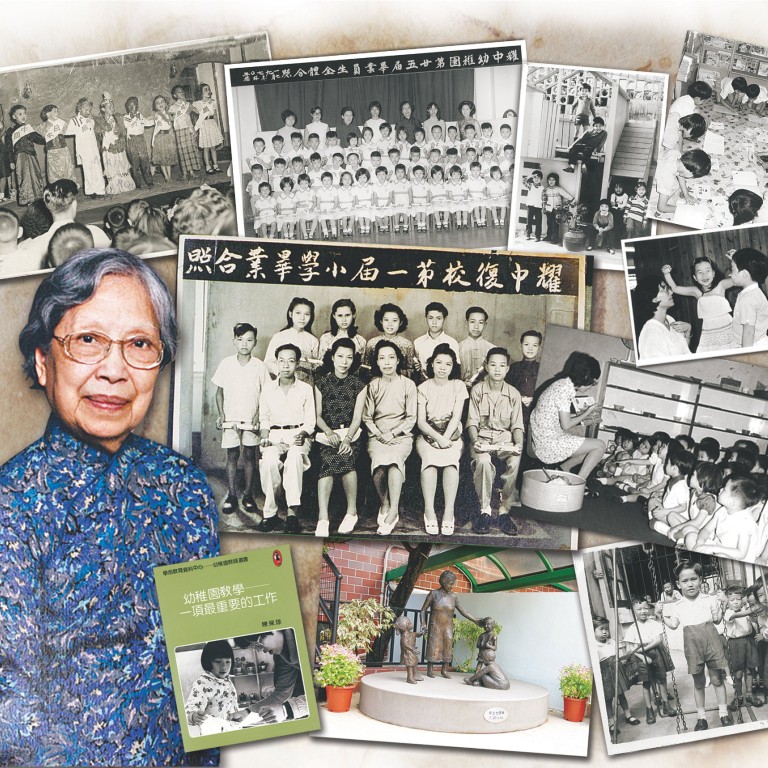

Building on a life of learning

Betty Chan picked up the baton handed to her by her mother and ensured Yew Chung school continues its passionate mission

Education runs in Dr Betty Chan Po-king's family.

Her mother started what would become a lasting legacy during a time of instability and poverty, with a civil war raging on the mainland.

Tsang Chor-hang, then just 16, decided to set up a school with her friends.

"My mother thought education was the most effective way to make China stronger and, as a Christian, she believed letting children know about God was the best gift she could give to them," Chan said.

The school, Yew Wah, which literally means "bringing glory to China", started with a small classroom at the corner of Bute Street and Nathan Road in 1927.

It eventually transformed into what is today the Yew Chung International School, which now has campuses in Hong Kong, on the mainland and in the United States.

Chan is the school's director.

Yew Wah offered primary education to children living in the nearby Kowloon neighbourhood, teaching Chinese poetry and gospel stories.

But it wasn't all plain sailing.

Some of the founders suggested closing the school after three years as it had run out of money. But the others insisted on carrying on because parents had already paid their fees.

"At that time, school fees were paid in rice. So even though there was nothing else left, they had rice to eat. They didn't take any salary," Chan said.

Tsang became principal when she was just 19 and when she got older became known as "Hau Cheung Po Po", or principal grandma.

"In my eyes, my mother was a heroine. She was very capable," Chan said.

She recalled how parents followed rituals to decide when their children should start school, taking into account their birth time and dates.

As for the youngsters, they had to turn up dressed smartly and apply themselves diligently to their lessons.

In 1932, Yew Wah was replaced by Yew Chung, with its first campus in Sai Yee Street. The school was forced to close seven years later with the outbreak of the second world war. It reopened in 1945 and had its first batch of post-war graduates the following year.

Chan eventually started at the school, but it wasn't easy for her.

"When someone had to be made an example of, I would usually be the first, to show there was no bias," she said. Tsang eventually decided it would be better for her daughter to be educated at another school, so Chan left Yew Chung after Primary Four.

Tsang retired after four decades of teaching and closed the school.

Chan, who had trained as a teacher in the United States, started working in a kindergarten operated by Caritas.

She did not like its strict, traditional style and started using the more relaxed, modern theories she had been exposed to in America.

"Nursery is the first place a toddler spends time outside home, so it has to be comfortable," Chan said, adding that most kindergarten teachers then had just a high school education.

In 1972, Chan opened a nursery in Kent Road, Kowloon Tong, and in honour of her mother named it Yew Chung.

A kindergarten followed, then the primary section in 1985 and secondary in 1992.

Her niece Lydia Chan Lai-seng, who also works at the school, started at Yew Chung when just 18 months old and was among the first graduates of the International Baccalaureate programme, which started in 2000. She went on to attend Cambridge and Oxford universities.

Betty Chan said she decided to open an international primary school after overhearing a conversation between a German father and his teenage son, who was on his way to Taiwan to study Chinese.

"I found the dad very insightful in wanting his son to learn Chinese," she said. "My first degree is in primary education, so I thought I could try starting an international primary school."

Chan said most international schools just brought in a curriculum from elsewhere, but she thought "international" should mean an integration of different cultures, instead of only Western.

The school adopted a bilingual policy, so Chinese and English have the same status. It has two principals, one representing the Western culture, the other one Chinese.

"Parents enrol their children in our school because they trust us," she said. "Sometimes I feel a lot of pressure as this style of education is my own invention."