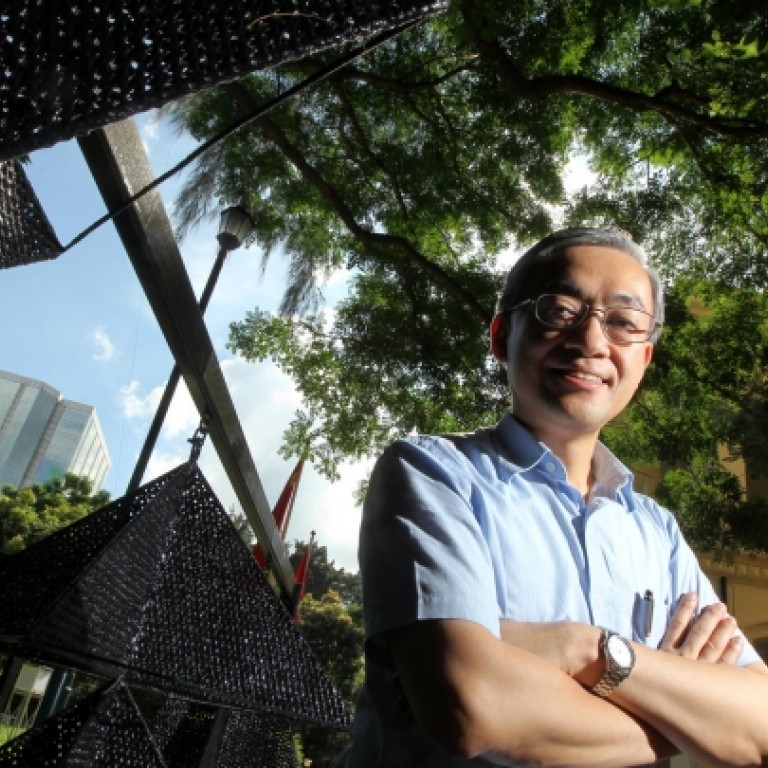

The Observatory's head in the clouds

Shun Chi-ming is Hong Kong's weatherman: he researches it, writes about it and sits atop 130 years of typhoons and bright ideas

For meteorologist Shun Chi-ming, it's science that helps him get his observations right, but it's past mistakes that help him interpret them wisely.

Shun became the 15th director of the Hong Kong Observatory in 2011 and he has spent the last 12 months delving deep into its history - all 130 years of it.

In his spare time, he has become an amateur historian, tracking down missing pieces of the jigsaw of the Observatory's past on the web, in obscure books and in museums, from bona fide historians and even flying abroad to meet former staff.

In the process, Shun has developed a great respect for his predecessors' achievements and has spent a lot of time reflecting on past natural disasters that killed tens of thousands.

"There are always lessons we can learn from history," he said. "That's why we must always bear in mind these historical catastrophes, even though today we have radar and satellites."

Among these catastrophes, two typhoons stand out. A typhoon of 1906 killed 15,000 people, 5 per cent of the population at that time; and another in 1937 left 11,000 people dead, 1 per cent of the population.

"The 1906 typhoon caught many people by surprise. The historical records show that the storm was actually quite small in size. While there were roaring winds in Hong Kong, it was very calm in Macau," Shun said.

Thirty-one years later, the covered the 1937 catastrophe in a four-page report entitled "Hong Kong's worst typhoon". It included a picture of a sampan that had ended up sitting in Des Voeux Road West.

Shun said: "Nathan Road was all flooded; fish were propelled onto second-floor balconies along the waterfront; Pedder Street was under water. It would be beyond our imagination if it happened today - what would happen to our MTR system?"

And Shun warned it could happen again. "We have no reason to believe that we can't nowadays have a typhoon as strong and devastating as the ones in the past. It is all a matter of chance," he said.

One thing that might have changed little since the Observatory was set up in 1883 is the great expectations of the public.

The first director, William Doberck, stepped down after being blamed by the press and the public for his failure to offer a timely warning of the devastating typhoon of 1906. The typhoon gun was fired just minutes before the storm hit on September 18. The city was standing right in the middle of the typhoon's path.

A foreign consulate was said to have complained to Governor Matthew Nathan over the sinking of one of its ships. An inquiry was held but the Observatory was absolved.

"The challenges we face are no different from those of Doberck and his successors," Shun said. "There are always different voices out there and every time, no matter what decision you make, you are bound to attract some sort of criticism."

But public expectations have sometimes been even harder to forecast than the weather.

In 1900, a hurricane hit Hong Kong and killed several hundred people. There had been an accurate forecast and timely warnings but people failed to take adequate precautions.

"The typhoon actually occurred in November and no one would have expected a hurricane signal could be hoisted that late," Shun said.

"Some people had also become less guarded since the summer when the typhoon guns were fired several times but it turned out the wind was not as strong as anticipated."

Shun, who is the only director to have hoisted a hurricane signal in the past 14 years - for the No 10 Typhoon Vicente last year - said he was constantly mulling over how to enhance communications with the public.

In the early days, the Observatory relied on hoisting physical signals, firing typhoon guns or even creating minor explosions to alert the public to dangerous weather. Later it used radio and television. But Shun says social media and mobile phones are the way forward now.

"Two years ago, the top three media for weather services and information were television and radio, followed by newspapers.," he said. But then the internet and mobile phones ousted the newspapers and last year they even overtook radio," he said.

The Observatory's digital platform now has about 100 million hits a day.

Shun has also set up a personal Facebook account, now with hundreds of friends, to maintain a dialogue with members of public interested in weather.

He has found the new platform effective in helping explain weather phenomena or certain decisions of the Observatory.

"In some cases, they even defend us," he said of visitors to the site.

The Observatory's role in international co-operation has also been growing, such as helping to run the world weather information service website since 2005.

Shun, who led a team developing a light detection and wind-shear alerting system for airports, is now the president of the Commission for Aeronautical Meteorology under the World Meteorological Organisation - the first Chinese person to hold this position.

Shun said his colleagues and predecessors at the Observatory had proved very creative in resolving problems.

One classic example was the building of their own makeshift satellite signal receiver in the mid-'60s to receive data from the weather satellite launched by the United States.

It made the Observatory among the first - perhaps second to the United States itself - to receive weather photos and data direct from the sky.

"We have kept our tradition of creative innovation. It is in our DNA," said Shun.

An exhibition to mark the 130th anniversary, "The Hong Kong Observatory - Under the Same Sky 130 Years", will be held at the Museum of History from July 10 to September 2. Admission is free.