From hellhole to centre of excellence

Hong Kong is today one of the healthiest places on earth and a leader in medical research - but it's been a long, tough road to get there

"Not all the wealth of the East would have lured us thither." This was what friends of British vice-consul Henry Charles Sirr told him in the 1840s, when the scourge known as "Hong Kong fever" was engulfing the territory, its settlers and new colonists.

In 1843, an estimated 24 per cent of the British garrison in Hong Kong and 105 European residents died of the fever.

Sirr, in his book China and the Chinese, published in 1849, called Hong Kong "the most unhealthy spot in China".

If Sirr and his friends had lived to see today, they would likely be both shocked and proud. Hong Kong is now not only one of the healthiest places in the world - judging by its life expectancy and low infant mortality rates - but also a significant contributor to global developments in medical care and research.

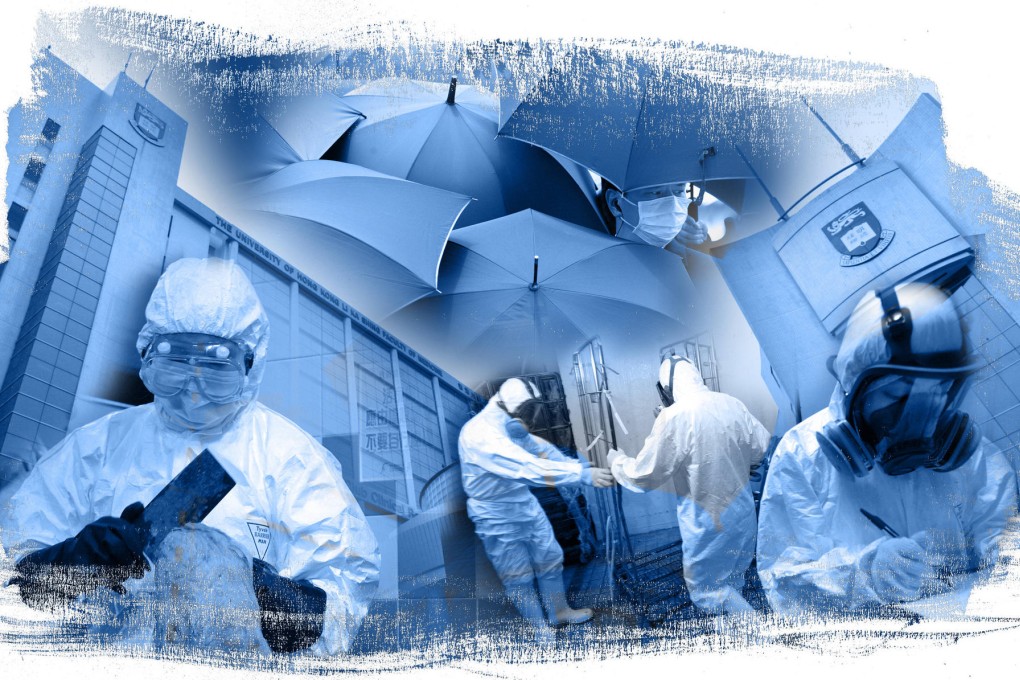

The "recent and remarkable achievements" that Ng highlights include pioneering research into emerging infectious diseases such as avian influenza (H5N1 in 1997 and this year's H7N9), swine flu and the Sars coronavirus, in terms of pathogenesis, clinical features, diagnostic tests, virus ecology, transmissions and treatment.

Hong Kong has also made notable contributions in the areas of spinal surgery, in-vitro fertilisation, endocrinology and transplantation. The city is also among the leaders in research on, and treatment of, diseases like lupus nephritis, a kidney disorder; leukaemia; liver cancer; nasopharyngeal cancer, which develops in the back of the throat; and hepatitis B. The latter two diseases are of particular significance because of their higher incidence rates in this part of the world.