Debate continues in Hong Kong over introduction of national education

One year after the government shelved compulsory national education, debate is still raging about how the subject can be taught

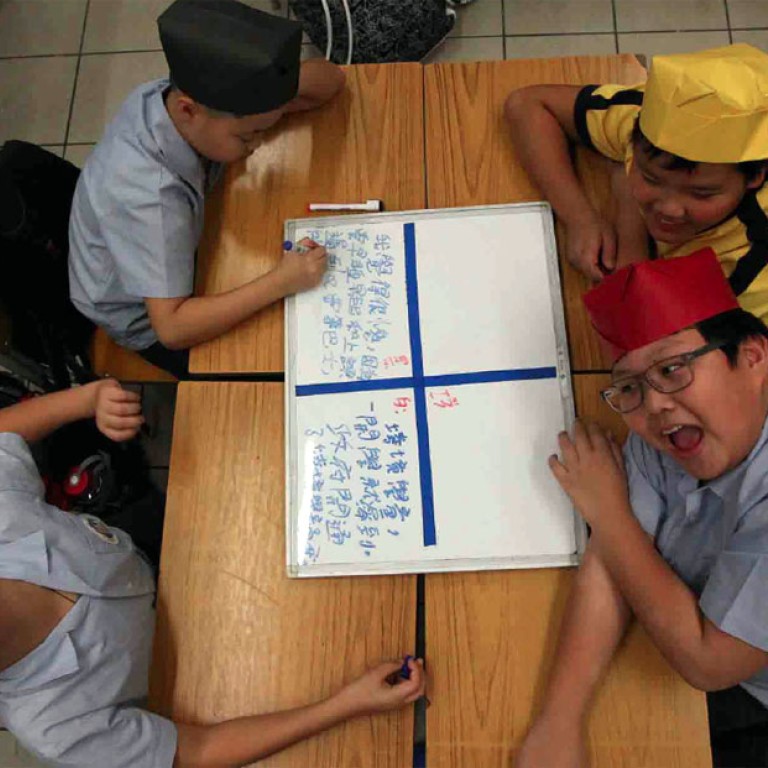

For many Hongkongers, the words "national education" bring to mind scenes of mass protest outside government headquarters. Ask a pupil at Fresh Fish Traders' School, however, and the word that springs to mind may well be: hats.

Lessons take the form of a discussion among groups of four pupils, each of whom wears a different-coloured hat. The child in a white hat speaks on the facts of an issue, the red hat is all about feelings, the yellow is for the positive side and the black hat is for the negative.

In a Primary Six class, the children discuss the influx into local schools of Hong Kong-born children living with their mainland parents across the border.

"They've come and taken away our school places," one boy sporting a black hat observes. "I'm afraid schools won't be able to hire enough teachers, and we'll all receive bad education."

"They'll receive better education in Hong Kong," a girl in yellow says with a giggle. "And Hong Kong will have more talents in the future."

The children are not graded, nor chastised for saying seemingly silly things. The classroom is filled with opinions and laughter.

The atmosphere could not be more different from the scenes this time last year, when tens of thousands of young protesters took to the streets, with some even joining hunger strikes. The government announced a year ago today that plans to make the subject compulsory would be shelved indefinitely.

And those who opposed the curriculum have no regrets.

"The national education subject was to teach children to love the country," said Ho Hon-kuen, vice-chairman of concern group Education Convergence. "It's very different from what national education should be based on: historical facts. Patriotism can't be taught.

"Now it's been a year since the shelving of the subject. I believe we should put the final nail in its coffin and bury it, but that doesn't mean that the discussion on national education itself should stop."

Despite the controversy, at least 34 of the city's 512 government primary schools had started teaching national education in some form, while at least 46 out of 454 secondary schools had done so by the end of last year.

Fresh Fish Traders' School started teaching moral and national education a year ago, though in line with the government's proposals there are no exams or homework. At the end of each term, pupils write a class report stating what their most memorable topics were and why.

Jackie Luk Lai-ming, 14, recalled walking into a classroom and seeing videos of tanks on the streets during the 1989 crackdown in Tiananmen Square, and learning that it is taboo on the mainland to speak of how many people died.

"If you've done something wrong you must admit it, or people will be suspicious," said Luk, who moved to the city from Shenzhen in 2008.

Lily Chan Lee-lee, whose daughter is in Primary Five, said they discussed topics from national education lessons at home, and she does not believe the classes will plant the seeds of blind patriotism. She encourages her daughter to listen to radio news and read newspapers to help her judge issues from different perspectives.

"I'm very much against requiring children to feel touched when listening to the national anthem or seeing the national flag," Chan said. "But if national education can teach students the development and weaknesses of China objectively, it's a good thing. It's similar to teaching children Chinese history."

Teacher Keith Yau Wai-kit, who is in charge of developing national education classes, said other topics included protests at the Guangdong fishing village of Wukan , which led to democratic elections for local leaders, and the 2011 train crash in Wenzhou . But the Occupy Central civil disobedience campaign has not been discussed as a future event would be too abstract for pupils, Yau said.

School principal Leung Kee-cheong says he wants his pupils to develop their Chinese identity by learning about different sides of the country, so they will want to change it when they grow up.

"Not all colours are black," he said. "Only after our children realise that there are things to be proud of as Chinese can they feel the need to save the country."

Elsewhere, the national education debate continues.

"Learning more about China is necessary, but we need to make the education neutral, so pupils can build their own stances on issues," said Agnes Chow Ting, a member of student-led group Scholarism, which was at the forefront of last year's protests.

Chow says national education should be based on well-rounded civic education, which encourages pupils to engage with society at large.

"Now we shouldn't focus on promoting national education again, because we still see many pupils receiving insufficient civic education," she said.

Baptist Lui Ming Choi Primary School in Sha Tin was supposed to be one of the first testing grounds for national education, but scrapped the subject after being targeted in some of the first protests, sparked by revelations that a Beijing-loyalist education group produced course material praising the Communist Party.

Isabella Lau Mo-yin, from the school, says the subject will not be introduced this year, but that it is inevitable that China-related issues will be discussed in other lessons.

Although most schools have steered clear of national education, parents opposed to the subject remain vigilant about signs of a patriotic agenda emerging in the classroom. The Parents' Concern Group on National Education is monitoring teaching materials and has found passages in various textbooks they believe are biased and mix emotions with facts.

Group convenor Eva Chan Sik-chee says some textbooks relate being Chinese to skin, eye and hair colour, ability to speak and write the language and being born to Chinese parents or in China. Such an approach would make Hong Kong-born ethnic minority children uncomfortable, she said.

Other textbooks, she says, skip over China's woes in the years between the founding of the People's Republic and the economic reforms of the late 1970s, while some require pupils to grade their pride in their national identity on a scale consisting of "good", "satisfactory" or "in need of more study".

"If schools offer national education without forcing children to be emotionally attached to their national identity, we respect them," Chan said. "They should also be transparent to parents … But what worries us the most is that many schools, although they don't have national education classes, are using textbooks that promote blind nationalism."

So is there a way to break the deadlock? A way of teaching children about their country while avoiding accusations of bias?

Education Convergence's Ho, who is also vice-principal of Elegantia College in Sheung Shui, believes the answer is yes.

He is adamant that a worthwhile national education curriculum should be rooted in facts, rather than a desire to force children to love their country. He therefore wants Chinese history revived as a compulsory stand-alone subject for Forms One to Three of secondary school - as it was, ironically, in colonial times.

While he has the support of establishment figures, some pan-democrats see his calls as an attempt to revive national education by the back door. But Ho has been fighting the cause for a decade, and says both sides are using the subject as a political tool.

Curriculum reforms in 2000 split Chinese history between other classes in the early years of secondary school. That led to fewer pupils taking it as an 8optional topic later on.

By contrast, other countries take national history more seriously, Ho added. The United States, for example, insists generals have at least a master's degree in American history.

"Historical facts about a country should be taught chronologically instead of in topics, so students can have systematic knowledge about it," he said. "If pupils don't know about China's historical facts, how can they criticise it or have any emotional connection with it?"

Parents' activist Eva Chan is, at least, open to the idea.

"It's perfectly justifiable for Chinese people to learn Chinese history," she said. "But its purpose shouldn't be cultivating a sense of identification."

Li Chin-wa, teaching fellow at the Hong Kong Institute of Education and co-author of a guidebook on civic education, said Chinese history and moral education should be incorporated into civic education, which he hopes will be taught in schools.

"If children only learn history, they still don't know the rights and responsibilities of a citizen," he said. "Civic education has a wider sociopolitical parameter.

"We're definitely against spoon-feeding pupils. What we want is to nurture politically literate citizens with critical, inquiring minds."