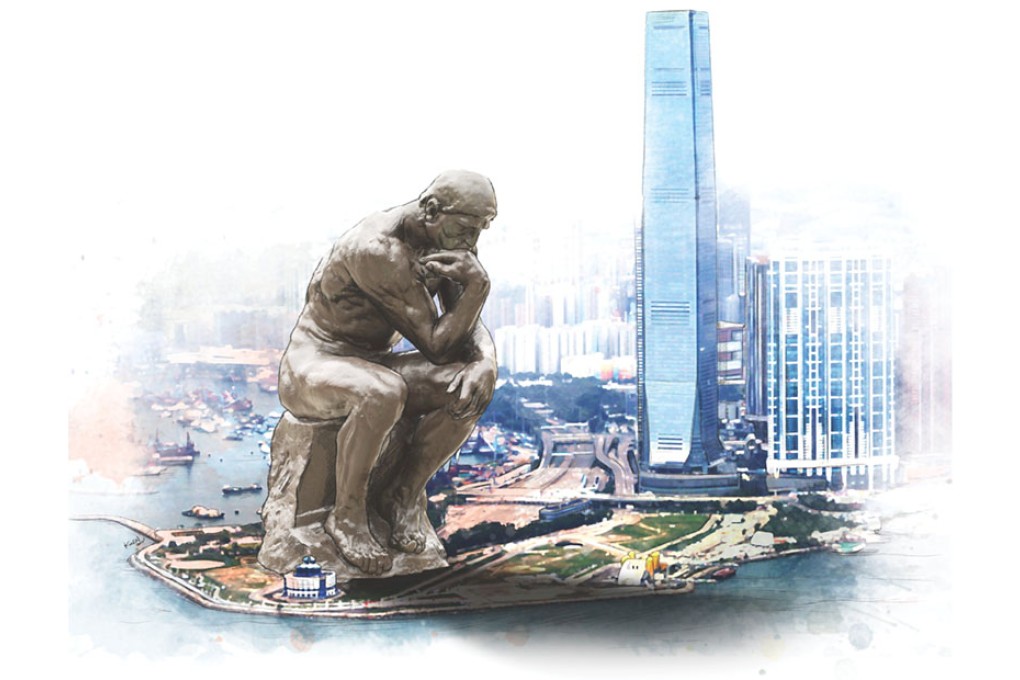

Time to rethink the vision for West Kowloon?

Fuzzy vision and problematic leadership - not delays and rising costs - are the cultural district's biggest problems, say board members

Sixteen years after the idea of building an arts and cultural district on reclaimed land in West Kowloon emerged, the site that promises to transform Hong Kong's cultural development is finally taking shape: a handful of facilities, including the Xiqu Centre and visual culture museum M+, are expected to be ready from 2016 onwards. Performances and exhibitions staged locally and abroad are gradually establishing the arts hub's brand.

The government has to pour in another HK$23 billion or perhaps more to build a basement that can contain all traffic underground to honour the design by Norman Foster's firm. A two-year delay in a cross-border express rail link terminating in the area means construction of the three venues sitting on top of the station will also be delayed.

But as the saying goes, problems that can be solved by money aren't real problems.

What really haunts the West Kowloon Cultural District are its fuzzy vision and problematic governance, say members of the arts hub's board and the city's cultural community.

Six years after the establishment of the West Kowloon Cultural District Authority, they are calling for a revamped board led by a chairman with vision and a management team headed by a CEO who can turn that vision into reality.

"What is the positioning of West Kowloon? How does West Kowloon fit in the cultural development of Hong Kong?" asked Arts Development Council member Ng Mei-kwan.