Hong Kong's HK$5b bid to boost R&D needs more research, academics say

Academics tell of the challenges involved in getting breakthrough work to market

A HK$5 billion injection for the Innovation and Technology Fund that was announced in this year's policy address may not in itself fulfil Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying's hopes of boosting the city's record on research and development, said academics, who called for long-term planning on top of cash.

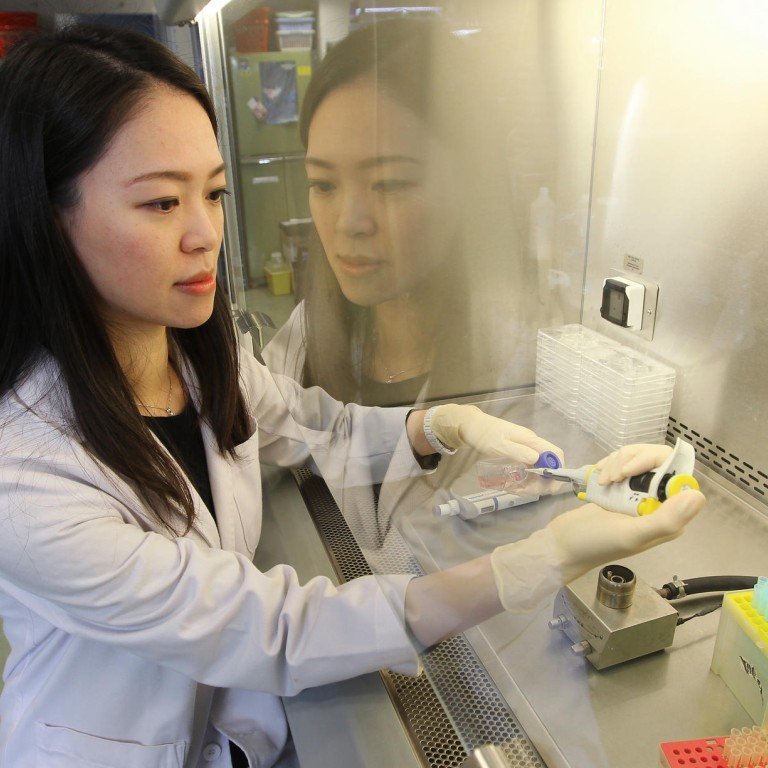

Despite her role in one of the city's major scientific breakthroughs, Dr Cathy Lui Nga-ping, of Baptist University's department of biology, knows from experience that commercialising academic research is no easy task.

And, Dr Alfred Tan Keng-tiong, the head of the university's knowledge transfer office, added that the sums of money involved went way over the sums to be allocated by the technology fund.

Two years ago, Lui and her team announced they had successfully used nano-particles to harmlessly extract stem cells from a rat's brain and then reinject them.

It raised the question of whether the procedure could be used on humans as a cure for brain diseases like Alzheimer's.

"We realised this technological breakthrough could indeed help a lot of people. That was when we started thinking about going commercial," Lui recalled.

She believes it will take another decade of work to turn research into application, with challenges both in the laboratory and beyond.

"Finding investors to fund the project is the biggest challenge," she said. "The United States and Singapore are enthusiastic when it comes to similar research but there are few biotech companies in Hong Kong."

Experiments on mice spell the beginning of the search for treatments that can be used on humans. It is then necessary to replicate the result on monkeys in clinical tests, before trials can be carried out on people. Each stage is extremely costly, which makes private support for projects essential.

The government scheme gives each of the city's eight universities a maximum of HK$4 million a year to support various startups.

"To open one biotech company, even HK$40 million would not be enough," Tan said. "This fund cannot achieve something once and for all. It only spells an opportunity, a beginning."

The risks involved in biotech projects mean investors are hard to find. Companies have to spend more than a decade in research, Tan says, but as a patent only last 25 years, the investors do not have long to profit from their investment. That's if the research is ultimately successful.

Another constraint felt in Hong Kong is the lack of research facilities for clinical research. It is possible to experiment on mice, but not on monkeys or humans, Tan said.

Such tests can be conducted at facilities on the mainland, but a lot of universities, both from the mainland and Hong Kong, are in the queue.

Other obstacles facing new high-tech companies are high rents and the lack of startup-friendly work spaces. Lui's team was selected for the Science Park's "incubation" programme, which aims to nurture technology startups, but many others are less fortunate, Tan said.

Scientists also require entrepreneurial training, he said. "They may have a PhD, but it doesn't mean they are experts in everything."

Professor Joseph Lee Hun-wei, the vice-president for research and graduate studies at the University of Science and Technology, said that apart from money, researchers needed the government to set long-term policies to encourage collaboration with the mainland.

Referring to the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement trade agreement which allows Hong Kong companies to enter the mainland market, he said: "There needs to be a CEPA for education and R&D."

Five Hong Kong universities have established their presence in Guangdong province and more than half of the research funding allocated to Shenzhen goes to Hong Kong academics, he said.

Many types of national funding could not be moved across the border, added Lee, while Hong Kong's Innovation and Technology Commission also restricted the amount of local funding that could be spent on the mainland.

He wants these restrictions relaxed for prestigious scientific projects, allowing research to be done simultaneously in Hong Kong and the mainland.