Inventor Professor Ron Hui says free-thinking is vital for Hong Kong's future

Hong Kong's freedom of expression has to be protected, but we must do more to boost creativity and make the most of innovation

Q: If Hong Kong could do one thing to boost its competitiveness, what would it be?

A: What the government should do is to maintain a stimulating environment

Hong Kong has shown it can lead the world in innovation - but it can only do so if it maintains its reputation for free-thinking while prioritising research, adding creativity to the curriculum and being prepared to take a few risks.

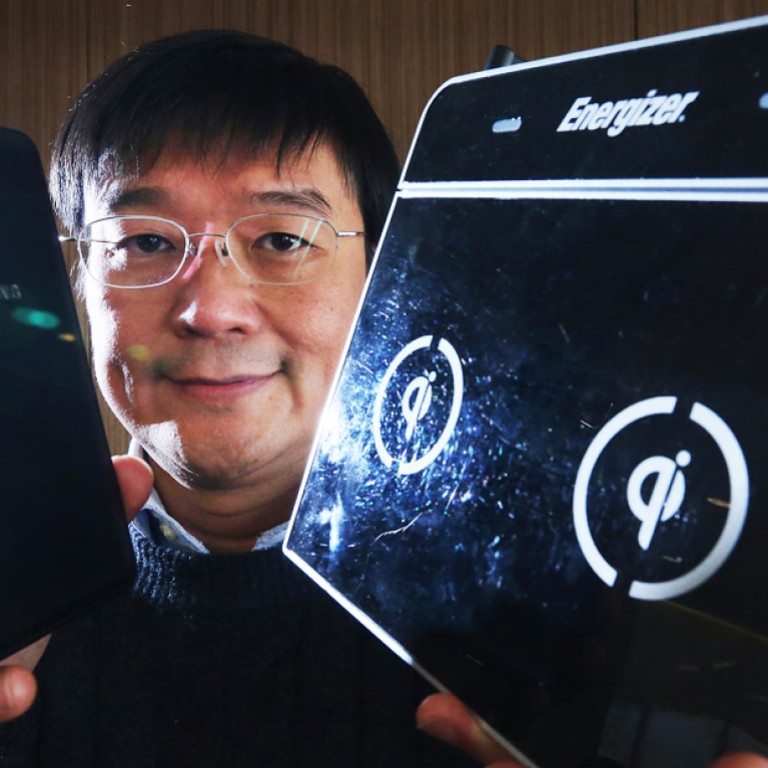

The man saying this should know. Professor Ron Hui Shu-yuen made a huge breakthrough in a field that has puzzled some of the world's most brilliant minds for a century.

The example of Hui, the chair in power electronics at the University of Hong Kong, shows it can be done. But his experience of trying to develop his innovation - a wireless charging pad for electronic devices - also shows the pitfalls.

From the start, local companies were nonchalant. "People were only interested in making smaller chargers, not wireless ones," he said.

The academic sees his success as a sign there is much right about the city in terms of freedom of expression and free flow of information. But it was Dutch company Philips that stepped in to licence his patents, while overseas institutions have applied his findings on a massive scale.

"It's Hong Kong which is losing out," he says.

To understand the magnitude of Hui's work, one must follow the story back to its origins - with an eccentric inventor and his "death ray".

About 100 years ago, Serbian-born inventor Nikola Tesla was working in his laboratory in Colorado Springs, USA. People walking along the nearby street would observe sparks jumping between their feet. The brilliant engineer had contributed to the technology used to supply electricity to this day. His new ideas, however, had peers thinking he was crazy.

Tesla believed it was possible to remotely shoot down an aircraft with an intense beam, which the press called his "death ray", and to get electricity to faraway villages wirelessly.

Fast forward to modern Hong Kong, where Hui became fascinated by Tesla's idea.

"When mobile phones started to take off in the 1980s, they each came with a charger. There were demands for companies to unify their chargers, but these were turned down," Hui recalled.

He soon realised: "To reduce electronic waste, there must be a product which is so user-friendly that the companies would have no choice but to adopt it."

And Hui found it. He developed a charger which could be used on phones of any brand, provided a plug-in was installed. And he realised his charging pad meant a host of gadgets could lose their cables.

While Tesla and the US space agency Nasa had experimented with wireless power, Hui had made the technology safe and user-friendly. He made sure gadgets could charge on any position on the pad, and introduced checks to ensure other metallic objects, like keys, would not be affected.

But taking his ideas to local companies proved disappointing. None were prepared to take it forward.

A few years later wireless transmission technology attracted the interest of overseas universities - and investment piled in.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States made headlines round the world with its work and launched a wireless electricity company called WiTricity, which has since developed applications for consumer electronics, health, the military and the auto industry, with one partner being Toyota. A similar project in New Zealand's Auckland University attracted investment from Samsung.

After years of local disinterest, Philips spotted Hui's work and formed a company in Hong Kong to license his patents. His research is the basis for the global standard in wireless power, Qi. The Qi logo is now used on products made by more than 100 companies, including Panasonic, Samsung and Sony. Ikea will sell furniture with built-in wireless charging spots in Europe and North America from next month.

Last year, Hui was keynote speaker at a conference in South Korea where the Advanced Institute of Science and Technology has built an "electric road" in Gumi city. It houses cables underground, creating magnetic fields which charge electric vehicles on the go. The breakthrough could popularise electric cars and cut pollution, Hui said, adding: "If the technology is applied throughout a city, it would solve the problem of having to find somewhere to charge an electric car."

But seeing how overseas institutions put the money into developing his innovation has only left Hui more frustrated.

He was told the electric road project, which powers Gumi's electric buses, cost HK$200 million - a sum it seems Hong Kong researchers can only dream of.

In 2013, total R&D spending in Hong Kong - both by government and private companies - amounted to HK$15.6 billion, just 0.73 per cent of the city's GDP. In comparison, that ratio was 2.1 per cent in Singapore and 4.04 per cent in South Korea, according to World Bank figures for 2012.

On top of that, companies overseas are willing to make high-risk investments in the hope of high returns many years later. Chinese firms, Hui says, will invest only in projects that are forecast to make a profit within three years.

In January's policy address, Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying proposed a HK$5 billion cash injection for the Innovation and Technology Fund.

Since it was established in 1999, the fund has provided HK$8.9 billion for more than 4,200 projects. It focuses on R&D projects undertaken by five centres set up by the government; collaborative projects between private companies and local universities; and in-house R&D in small enterprises. It also provides funding support for patent applications.

But Hui believes the fund needs changes.

First of all it needs to become more flexible. He lost out on a HK$100,000 subsidy for a patent application as the invoice was sent out after the funding deadline, even though the patent application itself was finished within the time limit.

Secondly there should be more emphasis on so-called upstream projects, allowing researchers to work on ideas that do not immediately appeal to manufacturers but have long-term potential.

He called on the government to allocate more funding to the Research Endowment Fund, set up in 2009 to support research in universities with money generated by some HK$23 billion in investments.

Hui said: "In General Electric, the company founded by Thomas Edison, there is a lab where scientists can do whatever they want."

Beyond funding, Hui said the local education system and parents needed to encourage more creativity in pupils. Hui, who studied at St Paul's College in Mid-Levels before going to a British university, said students in the city focused too much on memorising from books and missed out on creativity.

"When I was a PhD student in Imperial College [London], I noticed the British students did not memorise equations. Rather, they spent their time coming up with new ideas," he said.

Moreover, many talented local science students were reluctant to pursue a career in research as they tended to make their choices based on the salary.

"Some students asked me if they study for a PhD, what kind of jobs could they get in Hong Kong," he said. "My reply has been: 'The world is so big. Why must you work in the city?'"

But Hui himself is proof that the city is capable of leading the world in innovation.

Hui said Hong Kong's freedom of expression and free flow of information, which facilitate the birth of new ideas, are key. "The strength of Hong Kong university students is their ability to think freely. It is difficult to innovate without it."

In this respect, he believed one of the most important things the government could do to push Hong Kong up the global economic rankings was to defend society's foundations, adding: "What the government should do is to maintain a stimulating environment."

Professor Ron Hui

Ron Hui Shu-yuen is the chair professor of power electronics in the department of electrical and electronic engineering at the University of Hong Kong.

He began his studies at the University of Birmingham in England and received his bachelor of science degree in 1984 before going on to study as a postgraduate at Imperial College London, from which he received his doctorate in 1987.

From there, he began his academic career at another English institution, the University of Nottingham, where he worked until 1990.

He moved to the University of Technology in Sydney in 1990 and was appointed as a senior lecturer at the University of Sydney in 1992.

Hui returned to his hometown of Hong Kong in 1996, becoming a professor at City University before being promoted to chair professor in 1998. He was associate dean of the faculty of science and engineering from 2001 to 2004. Since July 2011, he has held chairs at both HKU and his alma mater, Imperial.

He invented wireless charging platform technology that helps underpin Qi, the world's first standard for wireless power. Hui has published more than 250 papers, and seen more than 50 patents adopted by the industry.

He is a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, the Institute of Engineering and Technology, and the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences & Engineering. Since 2013, he has edited the IEEE's .

In 2010, he received the IEEE Rudolf Chope R&D Award and the IET Achievement Medal, the Crompton Medal. This year, he received the IEEE William E. Newell Award.