Hong Kong dentist designs robots to detect and clear mines in Cambodia

After gaining fame for designing space exploration tools, Ng Tze-chuen sets his sights on helping Cambodia deal with an old scourge

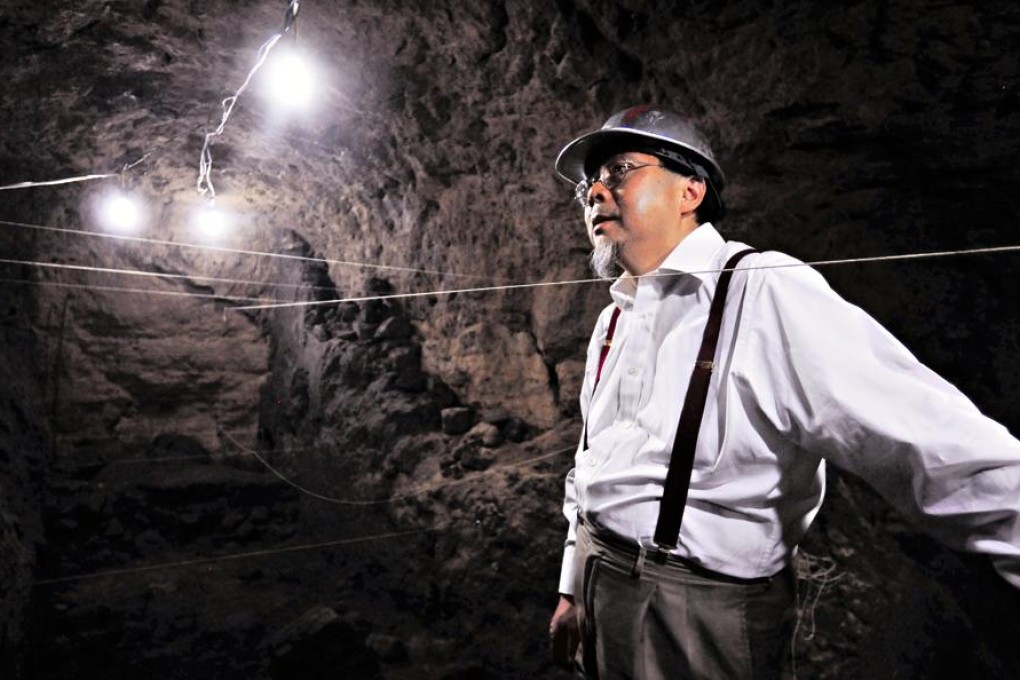

A Hong Kong dentist famous for his designs of space exploration tools for international space agencies is now building robots to detect landmines for Cambodia.

A series of remote-controlled robotic devices being designed by Dr Ng Tze-chuen can both detect mines and trigger explosions.

“Cambodia is one of the most heavily mined countries in the world,” he said. “Even today, its people still suffer heavy casualties from unexplored mines and ERW (Explosive Remnants of War)”.

Prototypes being developed include a drone that carries a carpet-like surface to detect mines using ultrasound.

Another is a multi-functional “robotic carousel”, with rotating arms that can detect mines, retrieve and collect them in a net, and detonate them on site.

Ng has designed and built exploration tools for space agencies in Russia and the European Union. His most famous designs were lost on the surface of Mars along with the British-built Beagle 2 carrying them on Christmas Day in 2003.