How Hongkongers have relied on loan clubs, pawn shops and underground banks for years

A look at the fascinating underground economies in use for centuries

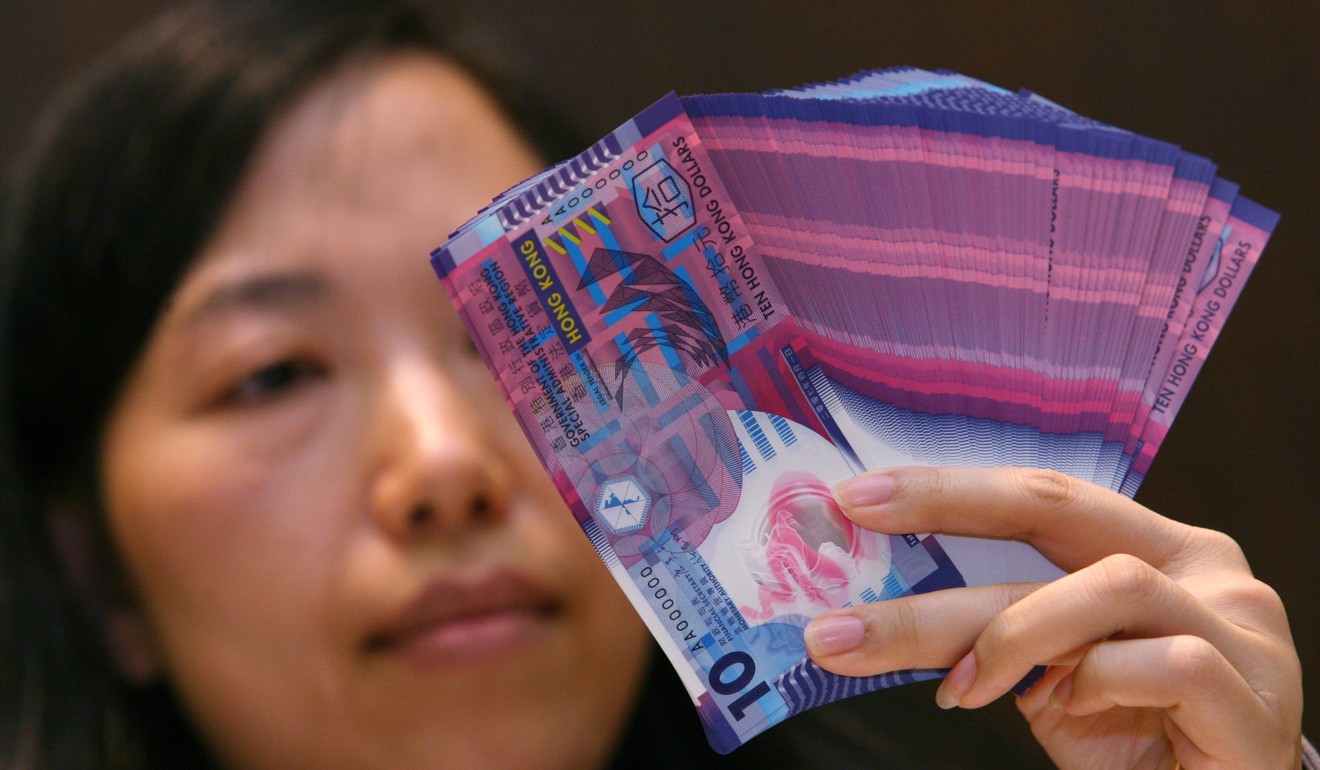

Despite being one of the world’s most well-developed, modern and vibrant financial centres, Hong Kong is also home to long-established informal methods of dealing with money.

These create fascinating underground economies that operate outside the stock exchanges and towering skyscrapers home to many of the city’s international financial institutions.

Many of these local moneylending systems have been in use for centuries, ranging from household loan clubs to the garish, neon-lit pawn shops spotted every few hundred yards in downtown Hong Kong and Kowloon.

The continuing survival of these practices offers a fascinating glimpse into local history, showing how Hongkongers often had to take matters into their own hands when raising money for household purchases or starting businesses.

But other back-channel financial systems such as underground banks are still criticised for enabling illegal activities such as money laundering and the trafficking of drugs, weapons and stolen goods.

Whether legal or not, these alternative financial systems are nonetheless examples of the enterprising drive and resourcefulness behind Hong Kong’s famed Lion Rock spirit.

Let them eat cake

Believe it or not, ordinary Hong Kong housewives pioneered the use of cake coupons as an alternative cash system in the 1970s and 80s. It all started with the rise of Maria’s Bakery, which was opened in 1966 by local entrepreneur Maria Lee Tseng Chiu-kwan, the city’s self-styled ‘queen of cakes’.

Before long, her home-grown business became Hong Kong’s most successful bakery chain, racking up profits of HK$700 million (US$89 million) a year through its franchise. At one point, Maria ran 70 stores in Hong Kong alone and a further 100 in Taiwan.

In the 1970s, Maria’s Bakery debuted cake coupons that customers could buy at a discount and later redeem for full-price baked goods. Housewives would trade coupons among one another, effectively forming an alternative currency.

Another “cake run” happened in 1998, when the Asian financial crisis forced Maria’s Bakery to pull down its shutters for good. But not everybody managed to redeem their coupons: an estimated 90,000 worthless vouchers were left outstanding.

However, such was the influence of Maria’s Bakery that coupon schemes were introduced by various other local bakeries and stores offering different products. To this day, cake coupons for luxury bakeries are commonly accepted as wedding favours, much like red envelopes.

Informal loan clubs: microcredit Hong Kong style

Also known as rotating savings and credit schemes, versions of these clubs can be found in most developing countries where peer-to-peer banking allows low-income earners to access a large sum of money without having to go through a bank.

In Hong Kong, these are known as gung wui (translates as “contributing to a club”) and typically involve a group of close friends, neighbours or family members who meet once a month to contribute a fixed amount towards a lump sum. A different member collects the sum every month until every member has received the pooled money.

From toys to money lending: the companies under investigation by Hong Kong’s watchdogs

Sometimes, the borrower is chosen through whomever bids the highest amount of interest they are willing to pay the other members.

Pawn shops

These iconic stores have been legal in Hong Kong since 1926, but pawnbroking was actually one of the earliest businesses in the city. Today, there are around 250 pawn shops in Hong Kong according to the Hong Kong and Kowloon Pawnbrokers’ Association.

Their survival till this day is down to Hongkongers’ keen appetite for quick-access, short-term loans that allow them to bypass all the paperwork and bureaucracy needed for a bank loan.

Pawn shops are regulated by the government. They may not charge more than 3.5 per cent interest per lunar month, and loans are restricted to HK$100,000 or under.

In past decades, customers would pawn electrical appliances and duvets, but due to their decline in market value, nowadays it is more common to pawn gold jewellery and luxury watches. Back then, poor families were especially reluctant to part with their duvets – often considered the most valuable and essential item at home.

Underground banks

In this way, a parallel black market has sprung up that can often move money more quickly and efficiently than cumbersome Chinese banks, which are heavily regulated by the state.

Revealed: the sneaky ways Chinese are moving money across the border

Each citizen cannot take more than US$50,000 out of the country per year, according to mainland Chinese law. However, Hong Kong does not have such a limit.

Beijing has spearheaded a number of crackdowns on underground banks in recent years, but failed to stop the outflow of cash completely as Chinese citizens scramble to get their cash out of the country amid a weakening currency and slowing economic growth.