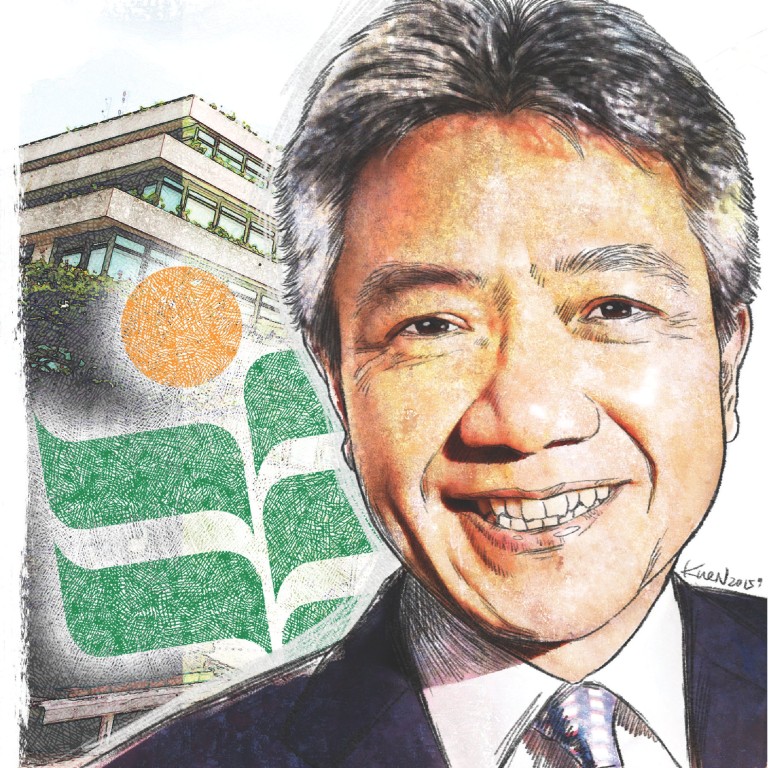

Title contender: university status will transform Hong Kong Institute of Education, says ambitious president

Gaining university status will transform the Hong Kong Institute of Education - and that's just the start for its ambitious president

What's in a name? Everything for the Hong Kong Institute of Education's president, Professor Stephen Cheung Yan-leung.

Turning into a university will mean more public recognition, more donations and more high-calibre students keen to take their degrees there and enter the teaching profession.

This is what drives Cheung.

"As president, [attracting] donations is one of my main tasks," he says. "Many people are very supportive of education - it's just that when you are an institute, they would rather donate to universities instead of you. This has been the difficulty we face."

Cheung - former dean of finance at Baptist University's business school who also chairs the supervisory committee of a bond fund under the Monetary Authority - has many connections in the business sector and government. But without the magic word "university" in HKIEd's title, his hands are tied.

"When I invited some people to make donations, they told me I should get back to them after [the institute] turned into a university," he says. "If you donate money to universities, maybe in return you can get an honorary doctorate degree or title. That makes a difference."

Last month the University Grants Committee submitted to the Education Bureau its recommendation for the institute to turn into a university, provided the future title contains the word "education".

Cheung says he expects the bureau to submit a report on the recommendation to the chief executive and the Executive Council around the end of the year. If the council endorses the report, it will bring the report forward to the Legislative Council.

If Legco approves it, the HKIEd will probably become a university in the middle of next year, which means students graduating next year will have a university title written on their degree certificates. Cheung says University of Education and Hong Kong Normal University, which he says implies education, are the most popular names among stakeholders.

Besides more funding, turning into a university would attract more secondary school graduates and more partners for exchange programmes, he adds.

But after it becomes a university, what next? Cheung has drafted a blueprint.

He hopes graduates can help shape Hong Kong's future education system, which can develop students with the creativity, innovation, morality and willingness to start their own businesses. Only when the younger generations acquire these qualities can Hong Kong maintain its competitiveness, he believes.

In the long-term, he wants to train teachers to be able to teach primary school children how to write smartphone apps in maths classes, a skill he describes as "very easy" to acquire.

He also wants teachers to encourage students to read by not forcing them to write reading reports but by letting them express their views about a book in whatever form they like, such as drawing a picture, performing a play or making a video.

For secondary students, teachers should teach them how to make a risk assessment for investment decisions, he says.

Last year, Cheung sent questionnaires to 2,000 school principals, asking them what qualities they would prefer when hiring teachers. Half the principals responded.

"The answers are consistent from kindergarten principals to secondary school principals," he says. They identified five main qualities: a positive outlook on life, a positive attitude towards work, a team spirit, communication skills and academic achievements.

Cheung says the institute is now preparing to fine-tune its programmes to include positive attitude education and education psychology to develop those qualities.

But the school will not open programmes not related to education, he says, as he and other teachers do not want the future university to deviate from what it set out to do.

Born in 1959 and growing up in a grass roots family with five siblings in Wan Chai, Cheung went to True Light Middle School's primary section. He then went to Tang King Po College, before entering Chinese University in 1978.

Only 2 per cent of students entered university in those days, he recalls. But as Hong Kong's economy started to boom there were more opportunities for young people with various industries offering many jobs.

"Property was much more affordable at that time as well. I graduated in the early 80s. The salary for fresh graduates was about HK$3,000 a month. Property was around HK$800 per square foot, so you could buy five to six square feet every month. Now you can't buy that much."

Cheung hopes the government, society and education system can encourage young people to pursue their own interests and talents.

"Society should give more opportunities and space for our young people to develop, instead of only focusing on their academic results," he says. "If they do not do well academically, they should still be able to develop their careers."

Stephen Cheung

56

Graduates from Chinese University with a bachelor of science degree in mathematics

PhD in statistics from University of Paris VI

PhD degree in finance from University of Strathclyde in Britain

Head of City University's department of economics and finance

Head of research at Securities and Futures Commission

Chair professor of finance at City University

Dean of finance at Baptist University

President of Hong Kong Institute of Education.