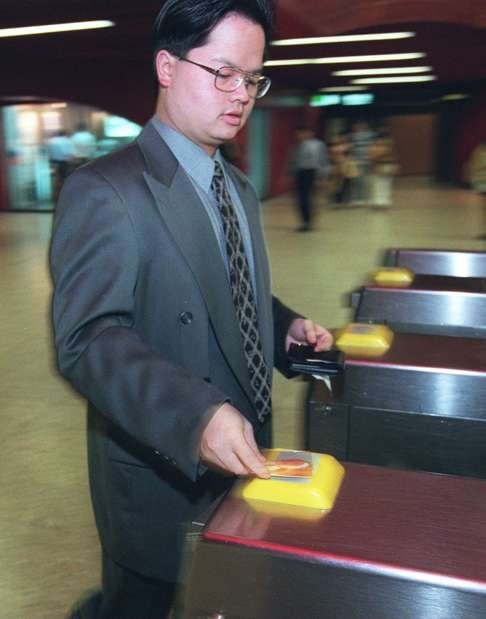

The man helping you get about town: developer of the Octopus card tells how his team revolutionised Hong Kong transport

Paul Chan Mo-lim and his team designed and implemented the automatic payment collection system over 35 years

A symbol of the city’s innovative side and efficiency, the Octopus card has impressed locals and visitors to Hong Kong alike since its debut almost two decades ago.

Launched as a stored-value card to be used on the MTR, it was quickly embraced by Hongkongers, who snapped up three million of them within the first three months of operation from September 1997.

The card’s Cantonese and English names were the result of a competition. In Cantonese it is known as baat daaht tung, which roughly translates as “eight arrived pass” or “go everywhere pass”. The number eight in the Cantonese name links it to the English name of the card, Octopus, which of course has eight tentacles.

The RFID (radio-frequency identification) chipped cards quickly expanded in use, and now a simple tap on a card reader can see it used to buy a range of goods and services from a beer at a 7-Eleven to natal services for the birth of a baby at a public hospital.

But while the Octopus card is recognised worldwide, the man behind the system has always kept a low profile.

Discovery Bay resident Paul Chan Mo-lim recently retired from his post as senior engineering manager for automatic fare collection systems with the MTR Corporation, and is now speaking out about his role in the development and ubiquitous application of the Octopus card throughout Hong Kong.

Q: What’s your background? Where did you study? Were you born in Hong Kong? Indeed, I was born here, but I left Hong Kong many years ago. My uncle opened a restaurant in England, so at that time they needed a lot of people who could help them because of a lack of labour, things like that. Although I was very young, I went over to stay at [my uncle’s] place and start my “restaurant life”. At the same time, I went to school and studied. I worked at the restaurant on week nights and at weekends.

Q: Was it a culture shock, going from Hong Kong to Britain? A bit. Luckily, I went to La Salle (Primary School). Even in those years that school was very English [focused]. So when I started to live there, and got used to British life, I enjoyed it very much. Up to university I worked as a waiter. I wore a white shirt, typical waiter attire. That’s where my English picked up. I then went to King’s College London and took a degree there in electrical and electronic [engineering]. In my final year, a company called General Electric Company, which was a big company in those years, [selected me] as a graduate engineer. I worked in England for less than a year. The reason is because at that time, on October 1, 1979, the MTR in Hong Kong started operations. The MTR recruited a lot of British people because there were no [local] experts. So they recruited a lot of people from London Transport and British Rail. The two companies basically set up the MTR in those days. I knew a guy I worked with in Leicester who came to Hong Kong and worked for the MTR. He immediately wrote to me: “Paul, come back to Hong Kong, the MTR has started.”

Q: Did working for this new, nascent company excite you? It excited me. You can understand, as a young guy who lived in the UK for years ... Because my home was still here, my parents still lived in Hong Kong, I was excited, but I thought, “Can I get used to [Hong Kong]?” I had gotten used to English life. I had a girlfriend [in England], I had bought a house there, I had a sports car there, so I was settled down. Suddenly, this opportunity came up and I thought, “Yeah, I’ll give it a try.” I asked my girlfriend, “Do you want to come back to Hong Kong?” She said: “No way.” OK, fine, so I set myself a limit of two years to see how it goes. I came to Hong Kong, had no interview, and immediately I joined the MTR just before opening day. I ended up working for the company for 35 years.

Q: Who was the brains behind “automatic fare collection”? Hong Kong started automatic fare collection [in Asia], meaning everything was [handled] by computers and machines. Singapore followed us four years later. I was a specification engineer. We wrote the specifications, we designed it and then we tendered out for a contractor to come in and provide a system to fulfil our requirements. So I was writing all the requirements and specs at that time to start this system. We bought a system from an American company called Cubic. The MTR, as an operator, tried to accept the system. When the system came in we installed, implemented, operated and maintained it.

Q: So where and when did the idea of the Octopus come about? In those days smart card [technology] was not mature. If you’re old enough, you will remember the MTR used magnetic-stripe technology for fare collection. This technology was running for nearly 20 years. At that time the director [of the MTR] said to me: “Paul, what can we do? We have a lot of fraud. We have a lot of people who try to cheat the system.”

Q: How would they cheat the system? Very simply. You went to Sham Shui Po to buy a magnetic recorder and tried to copy the information on the magnetic-stripe and then copy it to another card. So there was a lot of fraud and cheating in the 1980s and early 1990s. I was actually the one in and out of police stations as the technical expert helping to prosecute those cheats. In the early 1990s, we started looking at the fraud. [We found that] every year something like 1 per cent ... of something like five million transactions per day, based on an average of HK$7 per person, [was being lost to fraud]. That was [a lot] of money. We knew we had to change [the ticketing system]. So in the early 1990s we started to look at mature technologies. I travelled to Europe to look at all the systems and smart card [technologies]. Eventually we decided to use the Sony chipset.

Q: How did you finally set up the system on the MTR? I set our team on building the system in 1994. We tendered out the requirements and a company called ERG, an Australian company, got the contract. So we started to do the design and build the system up with them. In 1997, we started operating. That’s when Octopus started.

Q: What kind of hurdles did you face building your team up to operations? I could write a couple of chapters on that. We already had a basic fare collecting system in place, but it was a new technology coming in, and a big quantum leap [from the old system]. Software was a big problem. Migrating from the old magnetic system to a new system, using different languages to write software for migration to a new system. This is still a big issue today. Another issue was all the rules. We had to change the fare reader, we had to change a lot of rules, we had to make a lot of changes every year. How could we ensure no hiccups? How could you ensure nobody tapped their Octopus and deducted the wrong fare? This was a very big issue.

Q: Seems like it was a high-pressure job? It was. I was finally able to relax after I retired. I’ve been [a senior engineer] for over 20 years. Here’s one story I tell a lot of people: Two o’clock in the morning, when the phone rang, I knew there was a problem. The most high-pressure year for me was 2007. That was the time of the merger between the MTR and the Kowloon-Canton Railway. It [merged] two different systems in one go, in one night. December 2 was the most high-pressure morning I ever had. If you’ll remember, there were still gates on the MTR side and the KCR side. So I had to design software [allowing a passenger] to tap the MTR exit and enter the KCR side without any issues. But I enjoyed the job very much.

Q: People say Octopus is falling behind because of other competing technologies such as Apple Pay. Do you agree with that? Has Octopus hit a peak in innovation? It’s not falling behind, but it has to commercially compete against [the other technologies] in the retail sectors more and more in the coming years. Keep in mind, if the other operators want to use the Octopus infrastructure they will have to pay a transaction fee to Octopus. So if, for example, Apple Pay wants to be accepted on the MTR or on a bus, they will have to pay Octopus a transaction fee. On a commercial basis, it’s still sound.