One man’s property brochure collection offers a window on Hong Kong’s architectural history

Alfred Ho keeps a forgotten aspect of the city’s housing market alive, and shines a light on how developers constantly adapt to maximise profit

It’s hard to tell now from the building’s inconspicuous look, with its paint peeling and dozens of air conditioning units jutting out from its beige walls, but Grandview Building in Mong Kok was once a highly sought-after residential property when it hit the market in 1978.

“Grandview Building is especially equipped with two high-speed, luxurious Toshiba elevators that move 350 feet per minute,” a description from a vintage brochure read. “Jump on and off conveniently; no hassle, no waiting.”

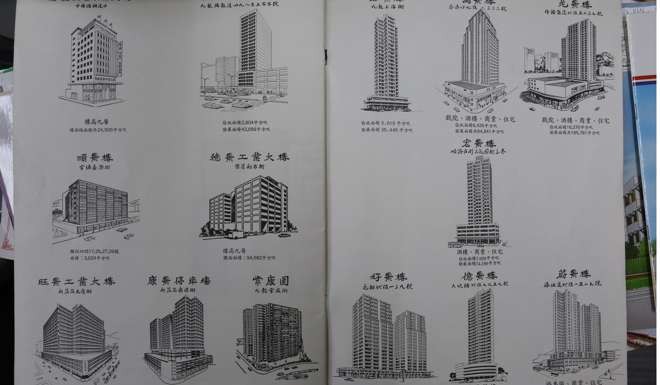

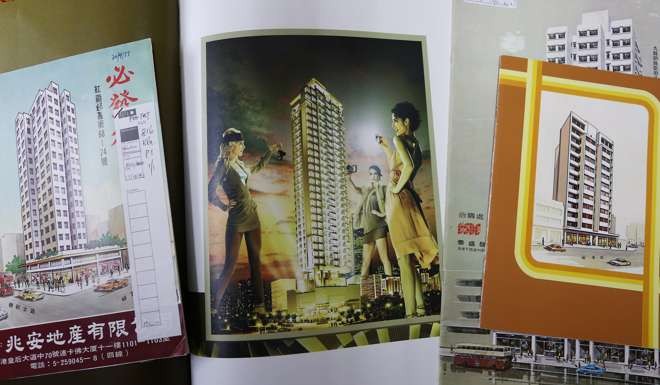

It is just one of the examples in a rare collection of over 3,000 home sales brochures printed since the 1970s that offer a glimpse of how Hong Kong’s buildings and neighbourhoods were built and formed over the past four decades.

The brochures, once a handy reference for architects to compare designs from competitors, became increasingly obsolete when a law in 2013 required all brochures to be available online, meaning architecture firms had no use in collecting them physically anymore.

“If I didn’t take them in, all this information about how people used to describe different parts of the city, and the buildings, would be lost,” said architect Alfred Ho Shahng Herng, who spent ten days lugging at least 30 sacks full of brochures to storage facilities and hopes to build a database for the public to access.

The vast collection is also a testament to how property developers have manipulated or exploited building regulations to maximise profit, giving rise to the city’s eclectic skyline and changing building designs over time.

“The building regulations were always changing, so property developers had to find clever ways to design flats in a way for them to maximise profit,” said Wayne Mak Kiu-yan, who works at Wong & Ouyang, a major local architecture firm.

“You’ll notice that flats built after 2004 all have balconies,” Mak said.

A government guideline in 2004 to promote construction of green and innovative buildings exempted certain features, such as balconies, from inclusion in each building’s given gross floor area (GFA).

“The exemption was like giving free GFA to developers to build beyond their original limit, so they could build bigger and also capitalise on it,” Mak explained.

It meant developers could profit from selling more or bigger flats according to the saleable area, as construction costs were only a fraction of what they could earn per square foot during the city’s then booming property market.

Housing estates in the past decade also took on peculiar shapes compared with boxy, rectangular layouts from the 1990s.

Mak attributed that to another regulation from 2002, which exempted pre-fabricated external walls from the building’s GFA.

They were exempted because the government wanted to reduce construction waste by encouraging developers to buy ready-made components from the mainland instead of building walls from scratch.

This spurred developers to design buildings in odd shapes since it required more external walls and would count into a bigger saleable area.

“These features are unnecessary, but they did it anyway so they could sell flats at a higher price,” Mak said.

Brochures dated before 1997 also reflected buyers’ concerns during the colonial era.

Covers stamped with slogans such as “More than 100 years of land lease remaining” were common, Professor Chau Kwong-wing, an expert in housing policy, explained.

“People then had no idea what would happen after 1997, and they assumed that they would have to hand it back to the government when the lease expired, so long land leases were a selling point. It gave people more security,” Chau said.

But since 1997, government policy stipulated that all land leases that expired then were automatically renewed for 50 years with the government charging landowners 3 per cent of the property’s rateable value.

“Nobody actually cares about the land lease these days, although [it does] expire,” Chau said, laughing.

The vintage brochures, many of them printed with hand-drawn watercolour plans, are also a stark contrast to brochures today of hundreds of pages that focus on glamorous clubhouse facilities and extravagant entrance lobby furnishings.

Grandview Building, built a year before the MTR started running, was described as “perfectly located in a quiet, but bustling area” next to cinemas and supermarkets, while being “only a stone’s throw away from buses and the Mong Kok Ferry Pier”.

The pier was demolished and later reclaimed under the West Kowloon reclamation project.