Hands-on art show opens up a whole new way of seeing ... and feeling

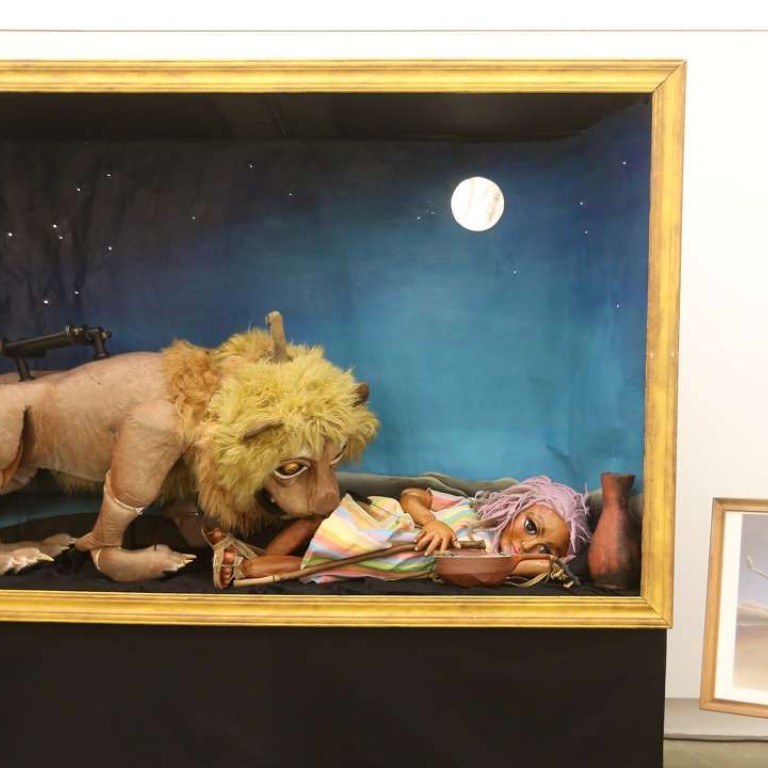

The fourth annual Hong Kong Touch Art Festival features work from around 30 artists that creates an experience inclusive of individuals who are blind or visually impaired

In most galleries and museums, signs remind you not to touch the artwork.

But at the fourth annual Hong Kong Touch Art Festival, visitors are not only allowed to touch the art, they are encouraged to.

The festival, organised by the Centre for Community Cultural Development, features work from around 30 artists centred on non-visual sensory experiences such as touch, sound and smell.

“It’s an experience, and it’s an experiment,” curator Wong Wing Fung said.

“It’s a new way of seeing every kind of artwork,” artist Brandon Chan Pak-kin said.

“Touch art is an inclusive art,” Fung and others wrote in an essay last year, published by the Arts Development Council. “We encourage inclusion: this means that we would not look at what others ‘cannot do’. We want to appreciate what they ‘can’.”

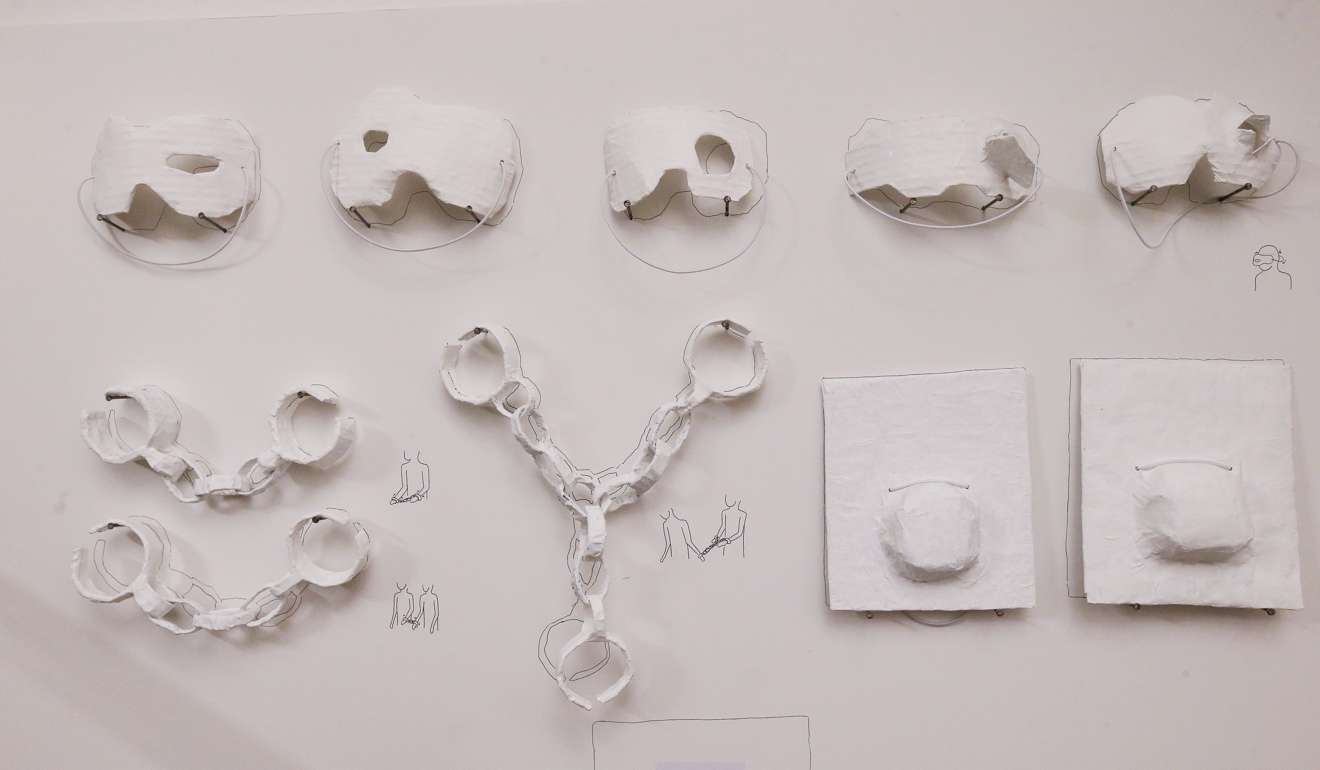

Many of the festival’s artworks were created by pairs of local artists and individuals who are visually impaired, including a joint piece by Chan and university student Ivan Tang – also a professional bowls player and part-time waiter.

Chan said the piece reflected communication, something he learned while working with Tang, as the two have different lifestyles and experiences.

“Communication between two people is something like this – you have to spend time,” Chan said as he leaned back against the bench, which lightened in response to his body heat. “I have to spend time on this seat to make this kind of mark. The process may take time, but the result is something you cannot express.”

People who cannot see have a different experience of art, often interpreting objects in a distinct, out-of-the-box way, according to Fung.

As a complement to the festival, she recorded two people with visual impairments verbally describing the pieces after touching them, such as a woman perceiving a figure of a mountain as a human face.

“This [different perception] is very close to what I believe is art,” she said. “Art is for people who can get away from reality for a moment, to realise things they don’t [ordinarily].”