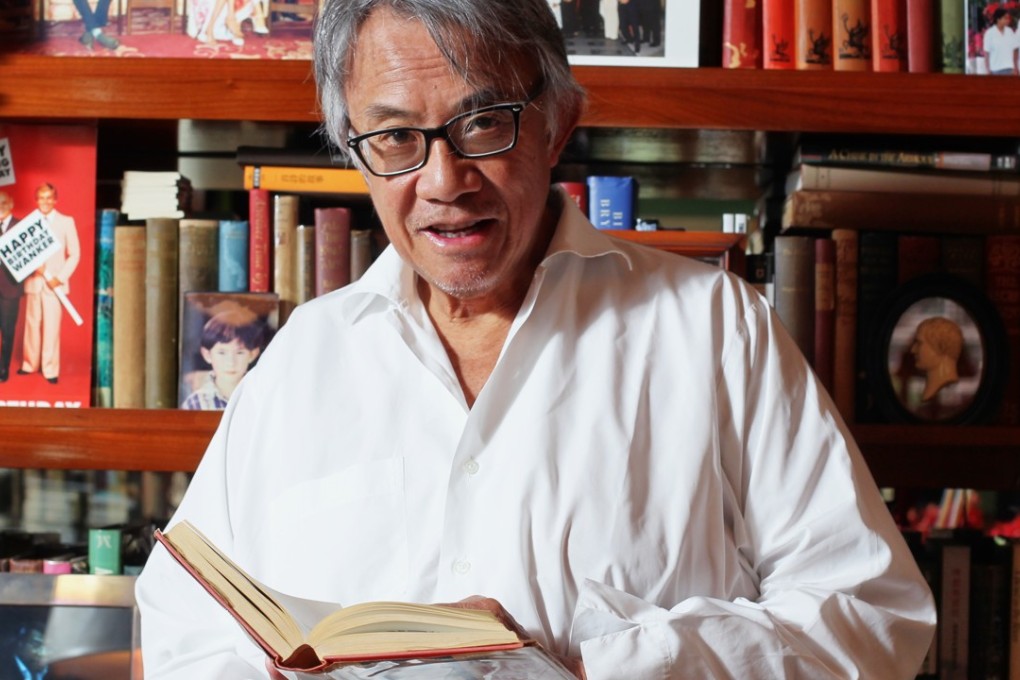

David Tang: the colourful life of the man behind Hong Kong’s fashion brand with a Shanghai twist

Flamboyant entrepreneur dies aged 63, leaving behind a rich legacy of arts, literature and philanthropy

“In business, I think I should’ve gone into property. I see all these people who made so much money, and they’re all stupid.”

In 1994, the Hong Kong businessman’s luxury clothes line redefined the garment industry and put him in a league of global celebrities – Tang was a globetrotter, rubbing shoulders with the rich and famous for the past 20-odd years.

He called renowned British architect Norman Foster “my old buddy”, and on one occasion danced with Queen Elizabeth. He lived the life of a socialite but emphatically refused to be called one.

“Thank you for alerting me to this excellent promotion. Except I am not sure I like being described as a socialite!” he wrote to the Post over a report on a Hong Kong Book Fair session in 2013, which he had personally invited renowned British authors to attend, all expenses paid for.