Infectious disease poses greater risk to diabetics

A world’s top microbiologist warned Hongkongers who have diabetes at risk of contracting a little known infectious disease after a Thailand research found the bacteria to be “severely underreported” in many places.

The bacteria, melioidosis, has a fatality rate of over 70 per cent and is commonly found in soil and water in Southeast Asia.

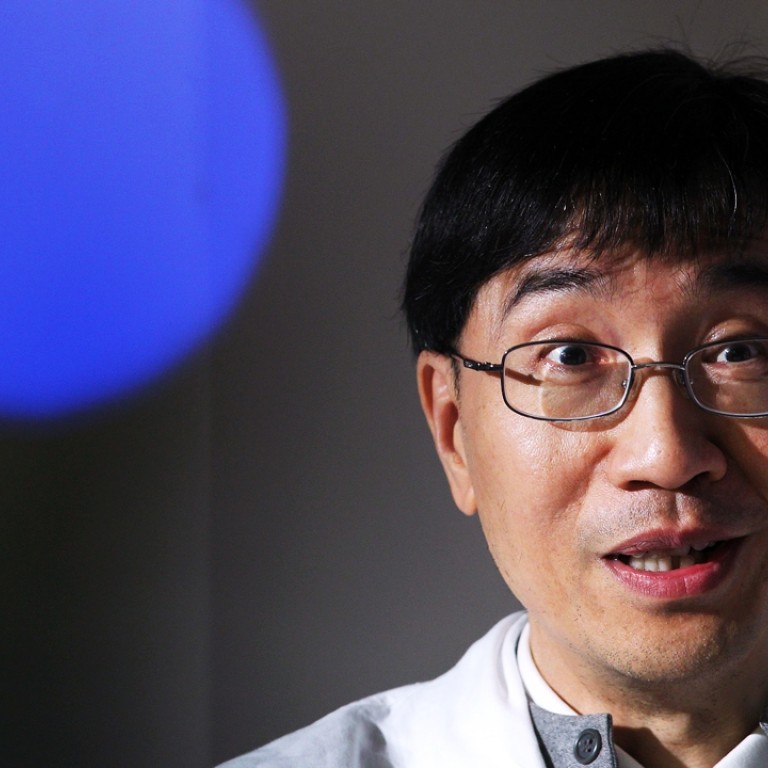

Though not listed as a notifiable disease by the city’s Centre of Health Protection, University of Hong Kong microbiologist professor Yuen Kwok-yung said some cases were seen in public hospitals every year.

“The most common presentation is acute pneumonia in a diabetic patients, but it can be found in other immunosuppressed patients,” said Yuen, the “Sars hero”.

He said the risk for the health risk for the bacteria to pose a public health risk remained low, as most Hongkongers are not farmers who have frequent contact with the soil. The infection were rarely seen in healthy adult previously.

But since there is an increasing number of diabetic patients, affecting 10 per cent of the population including children, he believed they should be on the alert and warned of the risk of soil contact.

Yuen explained the bacteria was brought up from the deeper layer of soil to the surface due to rain flooding or blown up by the wind, and local patients usually get the disease by inhalation, and contact with soil. Some, in rare cases, by ingestion of the bacteria.

“Note the risk of getting melioidosis is particularly high during the rainy and windy season,” Yuen said.

The melioidosis outbreak took places several times among the dolphins in Ocean Park, killing two dolphins between 2002 and 2009.

The disease was more well known to the world during the Vietnamese war, when the helicopter blades blew up dust from the ground. The US soldiers inhaled it and quite a lot of them got melioidosis, said University of Hong Kong’s honorary consultant tropical medicine Dr John Simon.

The experts’ remarks followed a the publication of a latest Thailand report on Nature Microbiology which predicts that melioidosis is present in 29 countries, including 34 that have never reported the disease.

The author recommends that health workers and policy makers give melioidosis a higher priority, and expects the number of melioidosis cases to rise as diabetes increases across the tropics, especially among the poor, and international travel increases the risk of introducing the pathogen to new areas.

“Although melioidosis has been recognised for more than 100 years, awareness of it is still low even among medical and laboratory staff in confirmed endemic areas,” said study co-author Dr. Direk Limmathurotsakul, Head of Microbiology at MORU and Assistant Professor at Mahidol University in Thailand.

“We predict that the burden of this disease is likely to increase in the future because the incidence of diabetes mellitus is increasing and the movements of people and animals could lead to the establishment of new endemic areas,” said Dr. Limmathurotsakul.

In reply, the Hong Kong’s Centre of Health Protection urged the medical practitioners to report the communicable diseases to them for prevention and control measures, despite it is not mandatory.