Hong Kong’s women struggle with cost, careers and cultural barriers in their family planning

Hong Kong has one of the lowest birth rates in the world, and boosting it will require overcoming economic, cultural and biological barriers. City Weekend looks at how women are approaching parenthood in 2017

In the last decade, the Hong Kong government has actively encouraged the city’s women to have more children. In 2005, then chief executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen suggested women should aim to have three children each, in order to help replenish the workforce and alleviate the problems caused by an ageing population.

Tsang’s comments, a marked change in tone from the “Two is Enough” campaign of the 1970s, came at a time when the city’s birth rate was declining.

In 2014, it was 1.23 births per woman – lower than mainland China and Singapore – making it one of the lowest rates in the world.

Long working hours, the rising cost of living and high property prices have been blamed for the trend. Academics have suggested one solution could be to offer priority on public housing waiting lists to families with two or more children.

Hong Kong will mark Mother’s Day tomorrow, but money is partly restricting how many women will be celebrating the occasion.

Research from the non-government organisation the Family Planning Association (FPA) suggests the majority of the city’s women who have no children have decided not to because of the financial cost (56.6 per cent), and a similar proportion (53.3 per cent) have chosen so because of the responsibility of having a child.

These figures, published in a 2012 survey, are almost the same for those women surveyed who have chosen to have only one child.

The study also found there was an increasing gap in the average number of children a woman had (1.24) and what they would ideally like to have (1.6). Estimates from the Bauhinia Foundation Research Centre suggest children are not cheap to raise in the city; the think tank suggests it could cost HK$5.5 million to raise a child from birth to college graduation for a middle-class family.

In 2015, an FPA television commercial posed the question “How many is enough?” as it told families; “The choice is yours”. It even suggested having as many as five children, or enough to “form a basketball team”. In an interview with the Post this week, Dr Susan Fan, the FPA’s executive director, rebuffed suggestions the sentiment was patronising to those who face financial and social barriers to having children.

“It was a tongue-in-cheek slogan,” she said. “The answer now is that it is your own choice. It was a deliberate response to the ‘Two is Enough’ campaign. But of course there are limitations for families.”

While admitting her opinions might be considered old-fashioned, Fan said she would encourage women to plan to have children earlier and not feel they have to have everything perfect in their lives to do so, rather than being “over optimistic” about getting pregnant in their late 30s and 40s and relying on human reproductive technology (HRT).

“HRT cannot overcome all the barriers of age,” she said.

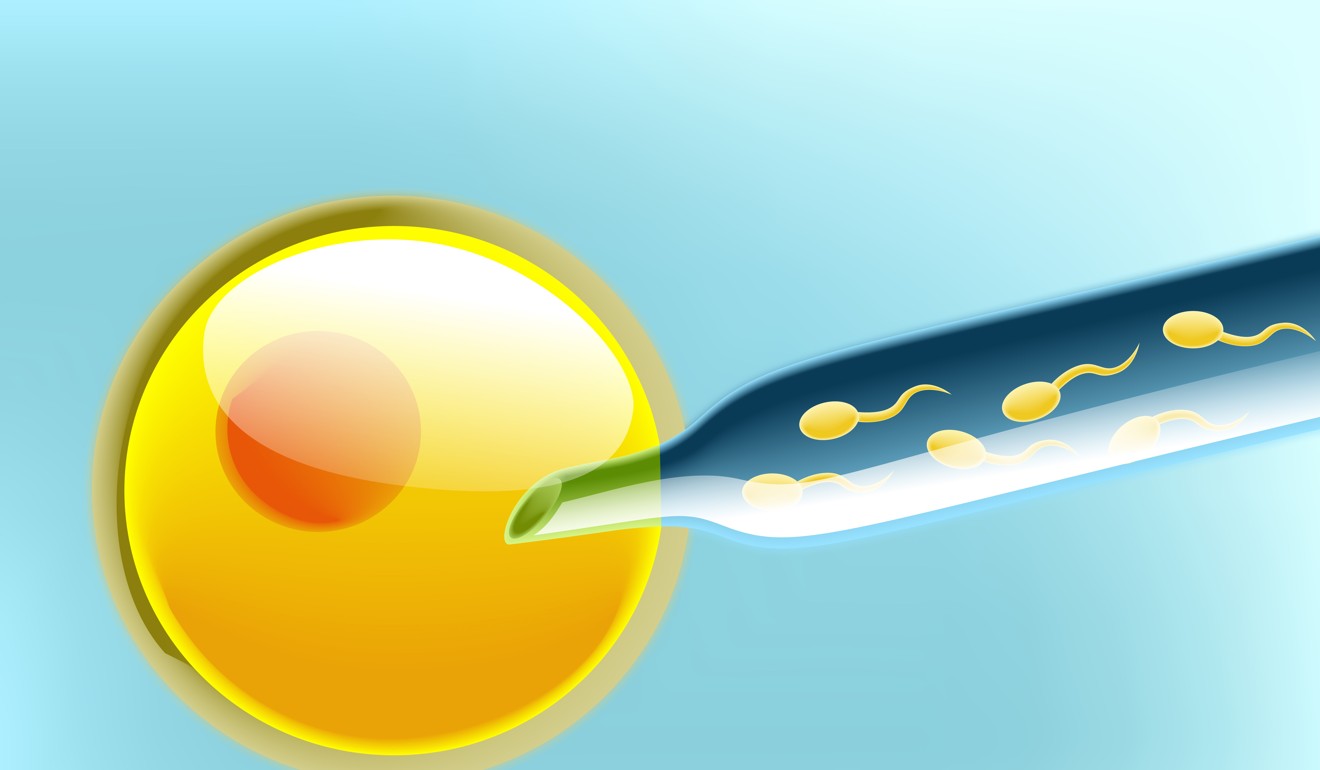

In March 2013, the FPA began offering artificial insemination procedures as part of its HRT services following increased demand from clients. The association began providing the service for about HK$10,000 – a fraction of the price at private hospitals, which charge between HK$80,000 and HK$100,000. But their manpower is limited and the number of resulting pregnancies has so far only reached 44.

Delaying motherhood

Hong Kong women are actively choosing to have children later in life, due to a combination of factors including being more career-focused and having increasing freedom to choose their partners. The number of women having babies over the age of 40 rose by 86 per cent to 3,391 between 2005 and 2014. But older women continue to face warnings that giving birth aged 35 and above increases the risk of harm to both the baby and the mother.

Dr Louis Chan Yik-si from the Hong Kong Reproductive Medicine Centre in Tsim Sha Tsui said the average age of his clients was about 37, adding that he had observed the age steadily increasing since he started working there five years ago.

He said most clients told him they had delayed having a baby until their 30s in order to focus on their career or to allow themselves more time to obtain better housing.

“There is a disconnect in Hong Kong between the society and the biology of having a child,” he said. “For women, fertility declines quite rapidly after 35. It is very unfair as men’s sperm quality goes down quite quickly after that point too, but not as fast as women’s eggs.”

Outdated fertility laws

Many working women face more than just biological barriers to conceiving naturally if they delay motherhood. It remains illegal for unmarried couples to undergo IVF treatment, according to laws set out in the 1997 Human Reproductive Technology Ordinance. Critics have long since maintained that the legislation is outdated and in need of reform, but the government appears reluctant to update existing legislation. The Equal Opportunities Commission’s recommendation to the government in March last year that the current law is discriminatory to unmarried and same-sex couples has so far been ignored by the government. Lawyer Winnie Chow, a partner at Hampton, Winter and Glynn in Central, said the current legislation was “clearly discriminatory”.

“Our current law is based on a mindset from a whole generation ago,” she said. “It was made on this ideal that the nucleus family is a married, heterosexual couple. If you think about the leaps and bounds made technologically since then, and how social norms have moved on so much, it is actually more common for the younger generation to be in a cohabiting, unmarried relationship.”

Meanwhile, Fan said the FPA “was not part of that debate” on IVF and could not comment on the restrictions.

Chow went on to say that the introduction of the Human Reproductive Technology Ordinance had not only outlawed surrogacy in Hong Kong, but made it legally difficult for couples to return to Hong Kong with a child born by a surrogate mother.

“The child is sadly deprived of any legal rights,” she said.

Despite the restrictions under section 17 of the ordinance, which came into effect in 2007, there remains no legal test case for surrogacy in Hong Kong.

High-profile cases

Speaking to the Post this week, Chan from the Reproductive Medicine Centre said he thought it was unlikely the government would update the current ordinance unless there were significant legal challenges to it.

Cultural barriers

One cycle of IVF costs about HK$100,000 in a private hospital. The cost is much lower at about HK$15,000 per cycle in a public hospital but this service is only open to women up to the age of 40 for a maximum of three cycles. Patients often face a three-year waiting list.

Chan said Hong Kong women might increase their chances of conception if they were willing to accept an egg donor for IVF treatment, but Chinese cultural values meant few were open to the idea.

“But I always say with fertility treatment, there is no right or wrong answer,” he said. “Treatments are a personal choice. Chinese culture means they are very reluctant to accept an egg donation.”

Increasing numbers of women are choosing to freeze their eggs, he said, but many cannot afford to do so until they are in their 30s, by which time they have fewer eggs which are also of reduced quality. The procedure may cost the client about HK$50,000 at a private clinic.

“People overestimate their likelihood of getting pregnant,” Chan said. “But we are talking about probability. You have to think about it in terms of how you would consider the odds of winning the Mark Six or winning the marathon.”

Aside from the cultural reluctance to accept donations, there is an extremely limited supply of both donor eggs and sperm because it remains illegal to pay donors for them in Hong Kong.

Fan does not think it is likely this law in regard to payment will change.

Elizabeth Quat, a member of the Legislative Council and chairperson of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong Women’s Commission, criticised what she said was the government’s failure to provide better financial support for families and would-be parents.

She said the DAB’s petition to the government last Mother’s Day, calling for an increased childcare allowance and more research into assisted reproductive services, had fallen on deaf ears.

Quat added she would welcome a government-sponsored scheme to make it easier for women to freeze their eggs until choosing to have children later in life, such as is the practice in Taiwan and Japan.

She said she would support an IVF policy which legalised the procedure for unmarried couples.

“I hope women will have that choice,” she said.