Ambitious move to save world’s smallest porpoise, led by Hong Kong Ocean Park animal expert

Plan is to capture, house and relocate vaquitas, a species so threatened by fishing by-catch that its population has dipped below 30

A veteran Hong Kong animal care expert will help coordinate a daring project to capture and protect the world’s smallest cetacean – the vaquita, a porpoise indigenous to Mexico that is on the verge of extinction due to an illegal fisheries trade closely linked to the city.

The scheme by Mexican authorities, a first of its kind, will employ specially trained US Navy dolphins to locate the critically endangered marine mammal – found exclusively in the Gulf of California.

The porpoises will then be captured by scientists and housed in offshore sanctuaries until it is safe for them to be released again.

“[Vaquitas] have never been captured before and we don’t know whether they will survive in captivity, but it’s a gamble worth taking at this juncture because if we don’t, they will be gone,” Grant Abel, a director of animal care at Ocean Park, said.

He will assist in the husbandry, housing and general care of the animals.

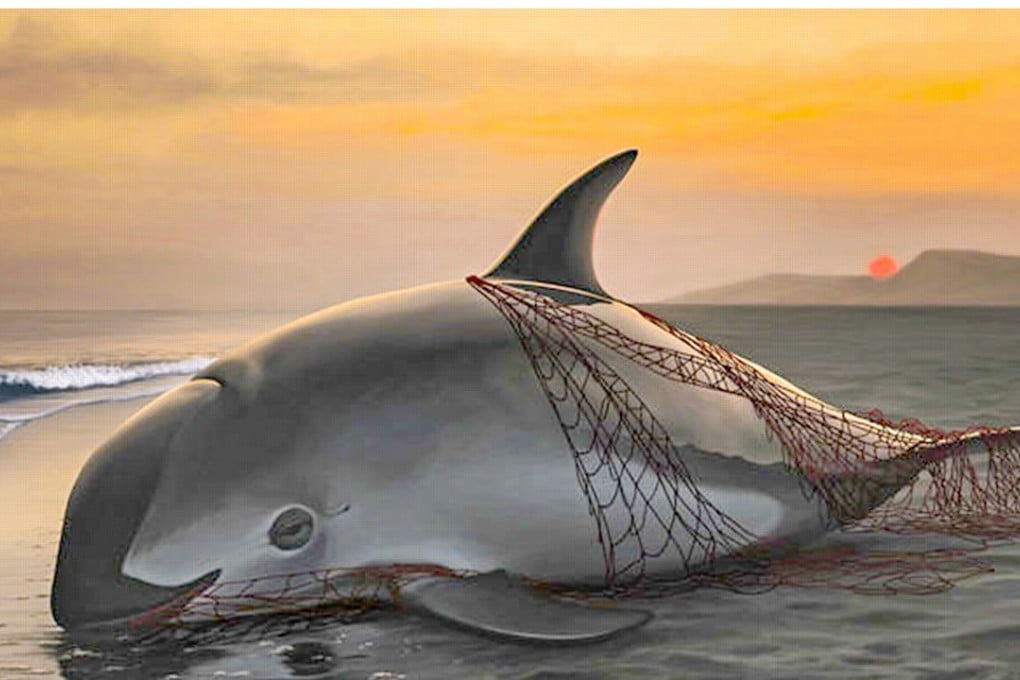

The vaquita population has plummeted by 90 per cent since 2010 and fewer than 30 are estimated to be left. The steep decline has largely been fuelled by poaching of the equally endangered totoaba fish, which is valued for its swim bladder.

Vaquitas often get caught and die in gillnets – vertical panels of netting – set illegally for totoaba. Both species live in the same area, and the international trade in totoaba is banned.